国務省出版物

米国の地理の概要 – ハワイ

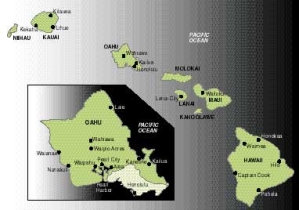

ハワイ群島は、さまざまな島やさんご礁が長さ3,300キロメートルにわたって、鎖状に連なり、太平洋中部に大きな弧を描いている。群島は東のハワイ島から始まり、ほぼ日付変更線のあたりの、大海の中のシミのようなクレ環礁で終わっている。ハワイ州の中でも、さまざまな大きさの島があるのは最東端から650キロメートルの範囲だけであり、人口もほとんどがこの地域に住んでいる。実際に「ハワイ」と見なされているのは、通常この部分である。

ハワイ州では、主要8島(オアフ、ハワイ、マウイ、カウアイ、ラナイ、モロカイ、ニーハウ、カホーラウエ)が面積の99%以上を占めており、ほんの一握りの住民を除くほとんどが、この8つの島に住んでいる。面積8,150平方キロメートルのハワイ島が、同州の総面積の3分の2近くを占めており、しばしば「ビッグアイランド」と呼ばれている。8つの島の中で最小のカホーラウエ島は、面積125平方キロメートルで、人は住んでいない。

ハワイは太平洋の真ん中近くに位置する。州都のホノルルは、カリフォルニア州サンフランシスコから西へ3,850キロメートル、日本の東京から東へ6,500キロメートル、そしてオーストラリアの沿岸部から北東へ約7,300キロメートルの距離にある。この位置関係をみると、ハワイは極めて孤立した状況にあるように思えるかもしれない。確かに、数世紀前だったら、その見方はおそらく正しかっただろう。しかし、環太平洋諸国間が互いに関係を深め、太平洋の資源を利用し始めるにつれて、これらの島々は交流の重要な中心となった。

ハワイは太平洋の真ん中近くに位置する。州都のホノルルは、カリフォルニア州サンフランシスコから西へ3,850キロメートル、日本の東京から東へ6,500キロメートル、そしてオーストラリアの沿岸部から北東へ約7,300キロメートルの距離にある。この位置関係をみると、ハワイは極めて孤立した状況にあるように思えるかもしれない。確かに、数世紀前だったら、その見方はおそらく正しかっただろう。しかし、環太平洋諸国間が互いに関係を深め、太平洋の資源を利用し始めるにつれて、これらの島々は交流の重要な中心となった。

ハワイ列島は、一連の巨大な火山群の中の、目に見える一部に過ぎない。この海域は深さ4,000~5,000メートルある。従って、火山が海上に顔を出すには、少なくとも5キロメートル近い高さが必要になる。

これらの島々を作り、今日も続いている火山活動の大半は、噴出物を遠くまで飛ばす爆発性のものではない。だが、爆発性の噴火から生まれた火山円錐丘も、実際にはハワイ諸島に存在する。その最大のものは、ホノルルの観光名所であるダイヤモンドヘッドで、高さはおよそ240メートルである。しかし、もっと一般的なのは、流出した溶岩が何層にも蓄積して形成された地形である。こうして形成された火山は、通常、ドームのような形をしており、険しい断崖ではなく、起伏した斜面が主な特徴である。

ハワイ島、別名「ビッグアイランド」には、いくつかの活火山が残っている。マウナロア山は平均して4年に1度、溶岩を噴出していて、その火山活動は、この島最大の町ヒロに、常に脅威を与えている。1950年の噴火の影響は、広さ100平方キロメートルに及んだ。もう1つのキラウエア火山も、常に活動を続けているが、実際に溶岩が噴出するのは7年に1回程度である。1960年の噴火では、キラウエア火山からの溶岩が10平方キロメートルにわたって流れ、島の面積が260ヘクタールほど増加した。

ハワイは険しい斜面が多い州で、標高も急激に変化する。これは海流によって火山の表面が浸食された結果である。波による海食崖は、島々のあちこちで迫力満点にそそり立っている。モロカイ島の北東部にある海食崖は海抜1,150メートルに及び、世界有数の高さを誇る。カウアイ島にある崖も600メートルを超える。「ビッグアイランド」の北東部を流れる小川の中には、海食崖の上から直接海に落ちているものもある。

河川による浸食作用で、溶岩層の表面はひどくえぐられている。火山ドームの多くは、渓谷で縞模様になっている。カウアイ島のワイメアキャニオンの底は、周りの土地よりも800メートル以上低くなっている。高さ数百メートルの滝も、ハワイ諸島ではよく見られる。オアフ島の「パリ」地区に崖が連なっていて、島の東西の正反対方向から土地を浸食しながら流れてくる源流が、ここで合流する。東に向かって流れてきた川は、川を隔てる尾根を浸食して広大な低地を切り開いている。一方、西に向かう渓谷はもっと深く、流れは尾根によって隔てられたままである。

こうした激しい浸食作用の一つの重要な結果として、ハワイ諸島では平坦な土地が限られている。カウアイ島は特に地形が険しく、低地は沿岸部の縁にわずかしか形成されていない。マウイ島には、島の両端の山の多い部分を隔てる、狭いが平坦な場所が中心部にある。モロカイ島の西側はある程度平坦である。オアフ島には中央部に広い谷間があり、沿岸部にもかなり広い低地がある。ハワイ島には、沿岸部に溶岩でできた平地がわずかにあるだけである。

周囲が海というハワイの立地条件は、明らかに気候に大きな影響を及ぼしている。ハワイ諸島の山々に吹き付ける風に水分を与える海である。さらに海は、気温の極端な変動を抑える働きをする。ホノルルの過去の最高気温は31℃で、最低気温は最高気温に似合った13℃である。

ホノルルの緯度は北緯20度で、カルカッタやメキシコシティと同じである。そのため、日照時間や太陽光線の入射角は、季節ごとの変化がほとんどない。この要因に加え、海洋に位置していることから、気温の季節変動もほとんどない。

ハワイ諸島で季節の大きな移り変わりを感じさせるのは、降水量の変化である。夏の間、ハワイは常に北東の貿易風の影響を受けている。この貿易風は、北東側を流れる寒流の上を通ってハワイに近づく。その結果、そよ風が吹き、雲はあるがよく晴れて、暖かいが暑くはないという、ハワイ特有の天気になる。冬期にはこの貿易風が、時には数週間も吹かなくなる。このため、北と北西から嵐が「侵入」してくる。ホノルルでは24時間に430ミリメートルもの雨が降ったことがある。ハワイの気象台は1時間に280ミリメートル、1日に1,000ミリメートルの降水量を記録したこともあるが、どちらも世界記録に近い数字である。

ハワイ諸島の地形は、場所により極端に異なる降水量をうみだしている。カウアイ島のワイアレアレ山では年間降水量が12,340ミリメートルに達し、世界でも降水量が多い場所の1つに数えられているが、同じくカウアイ島のワイメアでは年間降水量が約500ミリメートルである。しかも、この2つの場所は25キロメートルしか離れていない。ホノルルの大都市圏内では、年間降水量が500ミリメートル未満の半乾燥気候にあるビーチの近くに住むことも、年間3,000ミリメートルも雨が降る熱帯雨林の端にある「パリ」地区近くの内陸部に住むこともできる。太平洋北西地域と異なり、ハワイの山岳地帯で最も降水量が多いのは、通常、標高600~1,200メートルのかなり低い場所である。

火山性土壌の多くは透過性に優れているため、水は急速に浸透し、多くの植物に吸収される前に排出されてしまう。従って、降水量が中程度か、それより少ない地域の多くは乾燥地帯のような様相を呈している。

ハワイ諸島が孤立していることと、気候が概して温暖で、自然環境が変化に富んでいることから、実にさまざまな種類の植物や鳥類が生息している。ハワイ原産で、野生ではほかで見られない植物は数千種類ある。ハワイだけに生息する陸生の鳥も66種類確認されている。興味深いことに、人間がハワイに来るまで、ここには陸生の哺乳動物はいなかった。

ポリネシア人によるハワイへの移住は、人類が最も大胆に海洋航海を行った時代の一こまである。彼等は何度も繰り返し、屋根がないカヌーで、小さな群島を隔てる大海原を航海する旅に出た。例えば、1,000年前にハワイへやってきた移住者たちは、ハワイから南西4,000キロメートルのマルケサス諸島からやってきたものと思われる。島にはポリネシア人がやってくる前の先住民がいたが、おそらくは新参者ポリネシア人によって吸収されてしまったのだろう。次に大量のポリネシア移民がやってきたのは500~600年前のことだった。

このような航海には大変な努力が必要だった。その負担が重くなりすぎたのは明らかだった。そのため、2度目の移民時期の後、ハワイは数百年にわたり、孤立した時代を過ごすことになる。この孤立した時期にハワイの人々は、絶海の楽園で複雑な社会組織を確立した。世襲の統治者が住民に対する絶対的な支配権を持ち、すべての土地を所有するという体制だった。ヨーロッパ人がハワイ諸島を発見する18世紀末までに、環境が快適だったせいで、ハワイの人口はおよそ30万人に増えていた。

ハワイに最初に訪れたヨーロッパ人は、1778年のジェームズ・クック船長で、ここをサンドイッチ諸島と呼んだ。クック船長は「ビッグアイランド」の海岸で殺害されたが、彼がハワイを発見したというニュースはヨーロッパと北米に届いた後、急速に広がった。この島々が北米とアジアの間の貿易を促す中継地点として最適の場所にあることが、たちまちのうちに、認識されたのである。

1820年代に捕鯨業は北太平洋に移った。その後50年間、ハワイは捕鯨船員の主要な休息・補給拠点になった。ほぼ同時期に、プロテスタントの宣教師たちがハワイにやってきた。多くの捕鯨船員と同様、宣教師たちは米国北東部の出身だった。彼等は伝道活動に大成功を収め、数十年の間、ハワイの住民に大きな影響を与えた。

ハワイに最初のサトウキビ農園ができたのは1837年だったが、有力なサトウキビ生産地になったのは19世紀半ばを過ぎてからだった。19世紀半ばから末までの間に、ハワイはサトウキビでは、世界でも主要な輸出地域の1つになった。

サトウキビ産業の発展によって、農業労働者が必要になった。ハワイ先住民が一時期使われたが、その数が減少したため、必要な労働力を賄うにはまったく足りなかった。そこで、1852年から1930年までの間に、大規模農場の所有者たちは40万人の農業労働者をハワイに連れてきた。その多くはアジア人だった。1852年にはハワイ先住民は全人口の95%以上を占めていた。しかし1900年には、総人口15万人強のうち、先住民は15%弱となった。その一方で東洋人が75%近くを占めるようになった。

1930年以降は、米国本土がハワイ新住民の主要な供給源となった。1910年には、ハワイのヨーロッパ系住民(ハワイでは「白人(Caucasian)」と呼ばれている)はほぼ5人に1人だったが、今では40%近くが白人もしくは白人との混血である。

ハワイの人口は、ヨーロッパ人の移民が始まる前がピークで、その後減少して、1876年には54,000人まで減り、そこから再び増加に転じた。1920年代初めまでにハワイ諸島の人口は、ヨーロッパ人がやってくる以前の水準に戻り、1988年には110万人になった。外からの移民によって、ハワイの人口の年間成長率は、全米平均を大きく上回っている。

ヨーロッパから移民がやってくる以前、ハワイの人口は各島に分散していたが、最も人数が多かったのは「ビッグアイランド」だった。しかし、ヨーロッパ人がハワイを発見して以来、人口は次第にオアフ島に集中するようになった。良港を持つホノルルが主要な港湾都市となった。

ハワイの政治史をみると、クック船長による発見後120年間は、激動の時代だった。1785年から1795年までの間、強力なカメハメハ王によって、さまざまな王国が滅ぼされた。宣教師の影響が強まるにつれて、ハワイ人統治者の権威が次第に失われ、19世紀には、その結果生じた政治的空白に乗じて、ヨーロッパの政治勢力がこぞってハワイに進出してきた。

しかし、米国人の役割が高まり、ハワイが政治的独立を失った場合には、米国に併合されるという状況が避けられなくなった。米国人の農場経営者の数が増え、影響力が増すにつれて、ハワイ政府に対する彼等の不満が高まった。1887年、農場主たちは、自分たちの支配下にある公選政府を君主に受け入れさせた。1893年、君主制は完全に打倒され、新たな革命政府は、米国による併合を直ちに要請した。最初は拒絶されたが、最終的には1898年に準州として併合を認められた。

併合された時点では、最終的にハワイを州と認めることについては何も取り決められていなかった。ハワイが米国の50番目の州になったのは、アラスカが米国への編入を認められた後の、1959年のことだった。

ハワイ全土のおよそ半分は政府所有である。そのうち80%が、連邦政府ではなく州政府の支配下にある。そのほとんどの土地は農業にあまり適しておらず、大半は森林保護区や保護管理地区の中にある。連邦政府所有の土地は、主として「ビッグアイランド」とマウイ島の国立公園内にあるか、もしくはオアフ島とカホーラウエ島の軍所有地である。

ハワイの全私有地のうち8分の7を所有しているのはわずか39人で、それぞれが2,000ヘクタール以上を所有している。そのうち6人は、州の総面積約104万ヘクタールのうち、それぞれ4万ヘクタール以上を所有している。1区画の規模が小さい私有地はオアフ島に最も多いが、ここでも大地主たちが全私有地の3分の2以上を所有している。ラナイ島とニーハウ島では、それぞれほぼ全域を1人の地主が所有している。そして、オアフ島を除くその他の島はすべて、大地主たちが全私有地の約90%を所有している。

こした大規模な土地所有の大半は、ハワイ諸島で野放図な搾取が行われた19世紀に起きた。それ以前は、君主がすべての土地を所有していた。君主制が政治的に衰退していくと、この土地はハワイ人以外の民間所有者の手に渡っていった。初期の頃の所有者が死亡すると、ほとんどの土地は子孫が直接相続するのではなく、信託管理に付された。このため、所有形態を変えて土地を分割することが難しくなった。その結果、土地価格が高騰し、狭い地区に人口が集中することになった。

1860年代以降、何十年もハワイ経済を牽引したのはサトウキビで、その後はパイナップルだった。1940年代末まで、経済の中心は農業だった。ここ数十年は、農業収入も多少増加は続けているが、相対的な重要度は下がっている。現在ハワイで農業に従事している労働者は、30人に1人である。

しかしハワイのサトウキビは、今でも全世界の収穫量のかなり大きな部分を占めている。パイナップルの生産量は年間およそ65万トンで、世界最大の供給地となっている。

経済統計全体を見ると、オアフ島にハワイ経済の80%以上が集中しており、圧倒的に重要な地位にあることがわかる。その他の島では、今でも農業の役割が大きい。ラナイ島とモロカイ島では、雇用と収入の多くをパイナップルに依存している。牧畜とサトウキビが「ビッグアイランド」ことハワイ島の経済の根幹を成しており、マウイ島とカウアイ島ではサトウキビとパイナップルが経済の中心である。

農業の重要度が低下して、ハワイ経済における支配的な地位を失うと、真っ先にその地位を襲ったのは連邦政府だった。過去数十年にわたり、ハワイに対する政府歳出額は経済全体の成長率にほぼ匹敵する割合で増加し、歳出全体のおよそ3分の1を維持してきた。そのほとんどは、太平洋有数の良質の自然港である真珠湾周辺の土地を含むオアフ島の25%近くの土地を所有する米軍からのものである。ハワイの労働者の4人に1人近くが軍に雇用されており、軍の職員とその家族がハワイ人口の10%以上を占める。軍隊は、ハワイで最も多くの文民の雇用者でもある。

毎年450万人以上の観光客がハワイを訪れており、観光業も主な産業の1つとなっている。観光は最も成長著しい経済部門で、ハワイの総収入に占める比率は1950年の4%から今では30%以上に増加している。

ハワイ諸島の主要な島々は、同じハワイ州の一部であり、地質学上の成り立ちも似ているし、広大な海洋の中では近接した位置にあるが、それでもやはり、それぞれの特徴がある。オアフ島は人口密度が高く、土地の利用度も高い。そして米国の都市部に共通する喧騒や混雑の風景を見ることができる。これと比べて、「ビッグアイランド」ことハワイ島は比較的ゆったりとした空間と広がりを感じさせる。大きな牧場や高くそびえる荒涼とした火山、ほとんど樹木のない広大な土地がある。陸地部分は5つの巨大な楯状火山に占められている。砂糖、牧畜、観光業が主要産業である。

熱帯植物が生い茂っていることから「ガーデンアイランド」とも呼ばれるカウアイ島は、激しい浸食によって作られた山、渓谷、断崖、滝などの見事な景観に恵まれている。この迫力ある自然環境によって、観光客の間で人気がますます高まっている。近くのニーハウ島は私有地であり、ニーハウ・ランチ・カンパニーとして運営されている。そこに住む数百人の住民は、ほとんどがハワイ原住民である。

ハワイ諸島で2番目に大きいマウイ島は、中央部の低地にある大規模農場と、その両側の険しい山々が、対照的な景観を見せている。西側の沿岸部を中心に観光開発が精力的に進められてきたため、1970年代から1980年代にかけてマウイ島は、ハワイ諸島の中で最も人口増加率が高かった。しかし、マウイ島の西側以外の地域はあまり変わっておらず、人口もまばらである。

モロカイ島の半分は牧場で、残りの半分は険しい山岳地帯である。北部の沿岸地帯には、高さ1,100メートルに及ぶ壮観な海食崖がそびえているが、南岸部には広大な海岸平野が広がっている。ハワイ諸島の中の、人が居住する島のなかでは、最も経済発展が遅れた島と言えよう。

ラナイ島とカホーラウエ島はどちらも、背がはるかに高いマウイ島の風下にある。そのため、どちらの島も乾燥している。恒常的な河川は、どちらにもない。パイナップルの生産がラナイ島で唯一の重要な経済活動である。米海軍がカホーラウエ島を管理しており、軍事演習に使っている。

*上記の日本語文書は参考のための仮翻訳で、正文は英文です。

Hawaii

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, An Outline of American Geography.)

Hawaii

By Stephen S. Birdsall and John Florin

The Hawaiian archipelago is a string of islands and reefs, 3,300 kilometers long, that forms a broad arc in the mid-Pacific. The archipelago begins in the east with the island of Hawaii and ends almost at the international date line with a small speck in the ocean called Kure Atoll. Only the easternmost 650 kilometers of the state contains islands of any size, as well as almost all of the state's population. It is this portion that is usually considered as the actual "Hawaii."

The eight main islands of Hawaii – Oahu, Hawaii, Maui, Kauai, Lanai, Molokai, Niihau, and Kahoolawe – contain more than 99 percent of the state's land area and all but a handful of its people. The island of Hawaii, at 8,150 square kilometers, comprises nearly two-thirds of the state's total area, and it is often referred to as simply the Big Island. The smallest of the eight, Kahoolawe, is 125 square kilometers and is uninhabited.

LOCATION AND PHYSICAL SETTING

Hawaii is near the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Honolulu, the state capital, is 3,850 kilometers west of San Francisco, California, 6,500 kilometers east of Tokyo, Japan, and roughly 7,300 kilometers northeast of the Australian coast. This might be viewed as a case of extreme isolation, and until the last few centuries this was probably true. But as countries around the Pacific Basin began to communicate more with one another and to use the ocean's resources, these islands became an important center of interaction.

The Hawaiian chain is merely the visible portion of a series of massive volcanoes. The ocean floor in this area is 4,000 to 5,000 meters below sea level. Hence, for a volcano to break the water's surface requires a mountain already approaching 5 kilometers in height.

The kind of volcanic activity that created the islands and that continues there today has, for the most part, not been of the explosive type in which large pieces of material are thrown great distances. Volcanic cones resulting from explosive eruptions do exist on the islands. Diamond Head, the Honolulu landmark, is the largest at about 240 meters. More common, however, are features formed from a gradual buildup of material as a sequence of lava flows piled one layer on top of another. The usual shape of volcanic mountains formed in this way is domelike, with the main feature being undulating slopes instead of steep cliffs.

Several of the volcanos on the Big Island remain active. Mauna Loa pours out lava on the average of once every four years, and volcanic activity poses a constant threat to Hilo, the island's largest town. A 1950 eruption covered some 100 square kilometers. Another volcano, Kiluea, is usually active, but lava actually flows from it about once in every seven years. A 1960 flow from Kiluea covered 10 square kilometers, adding some 260 hectares to the island's size.

Hawaii is a state of rugged slopes and abrupt changes in elevation. This is the result of the erosion of the volcanic surfaces by moving water. Sea cliffs cut by waves form a spectacular edge to parts of the islands. Such cliffs on the northeast side of Molokai stand as much as 1,150 meters above the water and are among the world's highest; others on Kauai exceed 600 meters. Some small streams on the northeast side of the Big Island drop over such cliffs directly into the sea.

Stream erosion has heavily dissected many of the lava surfaces. Canyons lace many of the domes. The floor of Waimea Canyon, on Kauai, is more than 800 meters below the surface of the surrounding land. Waterfalls several hundred meters high are common on the islands. The Pali, on Oahu, is a line of cliffs where the headwaters of streams eroding from opposite sides of the island meet. Those flowing east have eroded the ridges separating them to cut a broad lowland; the westward-facing valleys are higher and remain separated by ridges.

One important result of this intense erosive action is a limited amount of level land on the islands. Kauai is particularly rugged, with the only lowlands formed as a thin coastal fringe. Maui has a flat, narrow central portion separating mountainous extremities. Molokai is reasonably flat on its western end. Oahu has a broad central valley plus some sizable coastal lowlands. The island of Hawaii has only some limited coastal lava plains.

Hawaii's oceanic location obviously has a substantial impact on its climate. It is the ocean that fills the winds with the water that brush the islands' mountains. The ocean also moderates the islands' temperature extremes – Honolulu's record high of 31°C is matched by a record low of only 13°C.

The latitude of Honolulu, about 20°N, is the same as Calcutta and Mexico City. As a result, there is little change in the length of daylight or the angle of incidence of the sun's rays from one season to another. This factor, plus the state's maritime position, means that there is little seasonal variation in temperature.

It is variations in precipitation that mark the major changes in season on the islands. During the summer, Hawaii is under the persistent influence of northeast trade winds, which approach the islands over cool waters located to the northeast and create characteristic Hawaiian weather – breezy, sunny with some clouds, warm but not hot. In winter, these trade winds disappear, sometimes for weeks, allowing "invasions" of storms from the north and northwest. Honolulu has received as much as 43 centimeters of rain in a single 24-hour period. Hawaiian weather stations have also recorded 28 centimeters in an hour and 100 centimeters in a day, both of which rank near world records.

The topography of the islands creates extreme variations in precipitation from one location to another. Mount Waialeale, on Kauai, receives 1,234 centimeters annually, making it one of the world's wettest spots, and Waimea, also on Kauai, receives about 50 centimeters annually – yet these two sites are only 25 kilometers apart. Within the metropolitan area of Honolulu, it is possible to live near the beach in a semiarid climate with less than 50 centimeters of rainfall annually or inland near Pali on the margins of a rain forest drenched by 300 centimeters of precipitation a year. Unlike the Pacific Northwest, the greatest precipitation on the higher mountains in Hawaii occurs at fairly low elevations, usually between 600 and 1,200 meters.

Much of the volcanic soil is permeable. This allows water to percolate rapidly, draining beyond the reach of many plants. Thus, many areas of moderate to low precipitation are arid in appearance.

The isolation of the Hawaiian islands, coupled with their generally temperate climate and great environmental variation, has created a plant and bird community of vast diversity. There are several thousand plants native there and found naturally nowhere else; 66 uniquely Hawaiian land birds have also been identified. Interestingly, there were no land mammals on the islands until humans arrived.

POPULATING THE ISLANDS

The Polynesian settlement of Hawaii was a segment in one of humankind's most audacious periods of ocean voyaging. These people set out on repeated voyages in open canoes across broad oceanic expanses separating small island clusters. Settlers who came to Hawaii 1,000 years ago, for example, are presumed to have come from the Marquesas, 4,000 kilometers to the southwest. There was some kind of pre-Polynesian population on the island, but it was probably absorbed by the newcomers. A second substantial wave of Polynesian migrants arrived 500 or 600 years ago.

The massive effort required by these voyages apparently became too great. As a result, Hawaii spent several hundred years in isolation after the second migration period. During the isolation, the Hawaiians solidified a complicated social organization in their insular paradise. Hereditary rulers held absolute sway over their populations and owned all of the land. By the late 18th century, when Europeans found the islands, the benign environment supported a population that numbered about 300,000.

The first European to visit Hawaii, which he dubbed the Sandwich Islands, was Captain James Cook in 1778. Cook was killed on the shore of the Big Island, but news of his discovery spread rapidly after reaching Europe and North America; it was quickly recognized that the islands were the best location for a waystation to exploit the trade developing between North America and Asia.

In the 1820s, the whaling industry moved into the North Pacific and, for the next half-century, the islands became the principal rest and resupply center for whalers. About the same time, Protestant missionaries came to the islands. Like most of the whalers, they were from the northeastern United States. They were very successful in their missionary work, and for decades had a major influence on the islanders.

The first Hawaiian sugar plantation was established in 1837, although the islands did not become a substantial producer until after the middle of the century. Between then and the end of the 19th century, Hawaii grew to the rank of a major world sugar exporter.

This development led to a need for agricultural laborers. Native Hawaiians were used for a time, but their declining numbers provided nothing like the labor force needed. Thus, between 1852 and 1930, plantation owners brought 400,000 agricultural laborers, mostly Asian, to Hawaii. In 1852, ethnic Hawaiians represented over 95 percent of the population of the islands. By 1900, they were less than 15 percent of the total population of just over 150,000, whereas nearly 75 percent were Oriental.

After 1930, the mainland United States became the main source of new residents in Hawaii. In 1910, only about one resident of Hawaii in five was of European ancestry (referred to in Hawaii as Caucasian). Now, nearly 40 percent of the state's population is Caucasian or part-Caucasian.

The population of Hawaii fell from its pre-European peak to a low of 54,000 in 1876 before beginning to grow again. By the early 1920s, the state's population had reached pre-European levels, and in 1988, the state had 1.1 million residents. Because of immigration, Hawaii's annual rate of population growth is well above the U.S. average.

The pre-European population was spread across the islands, with the Big Island occupied by the largest number of people. Since European discovery, the islands' population has been concentrated increasingly on Oahu. Honolulu, with its fine harbor, became the principal port city.

The political history of Hawaii was turbulent during the 120 years after Cook's discovery. The various kingdoms of the islands were eliminated by a strong chief, Kamehameha, between 1785 and 1795. The missionaries' growing influence gradually made a sham of the authority of the Hawaiian rulers, and, during the 19th century, competing European political interests moved in to fill the resulting vacuum.

But the increasing role of Americans made it inevitable that, if Hawaii was to lose its political independence, it would be annexed by the United States. As American plantation owners increased in number and influence, their dissatisfaction with the Hawaiian government grew. In 1887, they forced the monarchy to accept an elected government controlled by the planters. The monarchy was overthrown completely in 1893, and the new revolutionary government immediately requested annexation by the United States. Initially refused, they were finally accepted as a territory in 1898.

No provision was made at the time of annexation for the eventual admission of Hawaii to statehood, and it was not until 1959, after Alaska was admitted to the union, that Hawaii became the 50th U.S. state.

THE HAWAIIAN ECONOMY

Roughly half of all land in Hawaii is government owned, with the state, not the federal government, controlling 80 percent of that land. Most of it is in the agriculturally less desirable portions of the islands, and the bulk is in forest reserves and conservation districts. Most federal lands are primarily in national parks on the Big Island and Maui, or in military holdings on Oahu and Kahoolawe.

Seven-eighths of all privately owned land in Hawaii is in the hands of only 39 owners; each owns 2,000 hectares or more. Six different landowners each control more than 40,000 hectares out of a state total of about 1,040,000 hectares. Smaller unit ownership of private land is most extensive on Oahu, but even there the larger owners control more than two-thirds of all privately owned land. Two of the islands, Lanai and Niihau, are each nearly entirely controlled by a single owner, and on all of the other islands (except Oahu) major landowners control about 90 percent of all privately held property.

Most of these large landholdings were created during the 19th century period of freewheeling exploitation on the islands. Land had previously been held entirely by the monarchies. This land passed into the hands of non-Hawaiian private owners during the political decline of the monarchy. With the deaths of the early owners, most estates have been given over to trusts to administer rather than passing directly to heirs. This has made it difficult to break up the ownership patterns, which has led to high land values and pockets of high population density.

Sugar, and later pineapples, fueled the Hawaiian economy for many decades after the 1860s. The economy remained primarily agricultural until the late 1940s. In recent decades, agriculture has continued to show modest gains in income, but its relative importance has declined. Only one Hawaiian worker in 30 is currently employed in agriculture.

However, Hawaii continues to provide a substantial share of the world's sugar harvest, and its production of pineapples is about 650,000 tons annually, making it the world's largest supplier of pineapples.

Gross economic statistics overwhelmingly emphasize the position of Oahu, where more than 80 percent of the state's economy is concentrated. The role of agriculture remains great on the other islands. Both Lanai and Molokai depend on pineapples for much of their employment and income. Livestock and sugar form the backbone of the economy on the Big Island, as do sugar and pineapples on Maui and Kauai.

As agriculture declined and lost its dominance over the Hawaiian economy, its place was first taken by the federal government. Over the past several decades, governmental expenditures have increased at a rate roughly comparable to the growth of the total economy, maintaining about a one-third share of all expenditures. Most of this has come from the military, which controls almost 25 percent of Oahu, including the land around Pearl Harbor, one of the finest natural harbors in the Pacific. Nearly one Hawaiian worker in four is an employee of the military, and military personnel and their dependents together represent over 10 percent of Hawaii's population. The armed forces are also the largest civilian employer in the state.

Tourism is a major industry, with over 4.5 million people visiting the state each year. Tourism has become the principal growth sector of the economy, increasing its share of total island income from 4 percent in 1950 to over 30 percent today.

INTER-ISLAND DIVERSITY

The major Hawaiian islands are part of the same state, they have similar geologic histories, and they are closely spaced in a vast ocean, yet each has its own character. Oahu is densely populated and intensely used, and it offers a view of bustle and confusion common to urban America. The island of Hawaii, the Big Island, by comparison has an air of relative space and distance, with large ranches, high, barren volcanos, and large stretches of almost treeless land. Its land area is dominated by five huge shield volcanoes. Sugar, cattle ranching, and tourism are its major industries.

Kauai, sometimes called the garden isle because of its lush tropical vegetation, is heavily eroded into a spectacular scenery of mountains, canyons, cliffs, and waterfalls. Kauai is becoming increasingly popular with tourists because of its dramatic physical environment. Neighboring Niihau is privately owned and is operated as the Niihau Ranch Company. Most of its few hundred residents are native Hawaiians.

Maui, the second largest of the islands, offers a contrast between the plantations of its central lowlands and the rugged mountains to either side. Tourist development, concentrated along the western coastal strip, has been intense, with the result that Maui had the most rapid rate of population increase of any of the islands in the 1970s and 1980s. Still, much of the rest of the island remains little changed and sparsely populated.

Molokai is half ranchland and half rugged mountains. Its north coast is dominated by spectacular sea cliffs as much as 1,100 meters high, while the south shore is a broad coastal plain. It is perhaps the least economically developed of the populated Hawaiian Islands.

Lanai and Kahoolawe are both in the lea of much higher Maui. As a result, both are dry. Neither have any permanent streams. Pineapple production is the only important economic activity on Lanai. The U.S. Navy administers Kahoolawe and uses it for military exercises.

[Stephen S. Birdsall is dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Michigan State University and is the co-author of four books and atlases, including Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada.]

[John Florin is chair of the geography department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Pennsylvania State University. His recent publications include Atlas of American Agriculture: The American Cornucopia with Richard Pillsbury and Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada with Stephen S. Birdsall.]