国務省出版物

米国の地理の概要 – 北部太平洋沿岸地域

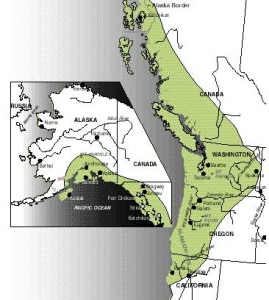

冷たい澄んだ渓流が、岩だらけの川筋を流れていく。その行き着く先は、険しい未開発の海岸地帯。霧に覆われた、切り立った崖が、打ち寄せる白波の上にそびえ立っている。遠くに見える山並みは、雪に覆われ、威風堂々辺りを払っている。そこに至るまでの土地は、背の高い針葉常緑樹の緑色のマントに覆われている。ところどころにある都市はまだ新しいといった印象である。これが、米国の「北部太平洋沿岸地域(North Pacific Coast)」、一般には「太平洋岸北西地域(Pacific Northwest)」と呼ばれる、北カリフォルニアからカナダ沿岸部を経てアラスカ南部まで続く沿岸地帯である。

「北部太平洋沿岸地域」の重要な特徴は、米国のほかの地域から相対的に孤立しているということである。この地域に住む人の数は、全米人口の3%未満である。この地域で人が住んでいる場所は、乾燥した土地や山によって、ほかの人口密集地から遠く隔てられている。この地域の多くの住民は、この孤立状況をほかの地域に対する地理的な緩衝機能とみなし、好ましく思っている。しかし、経済的には障害だったのである。「太平洋岸北西地域」で生産される製品は、輸送コストがかさむため、遠く離れた東部の市場では価格が高くなる。このため、この地域に生産拠点を構えることを思いとどまるメーカーもある。

「北部太平洋沿岸地域」の定義は、主に自然環境に基づいている。ごく簡単に言うと、ここは海洋と険しい地形の影響を強く受ける地域である。降水量は多く、高い湿度を好む植物が海岸近くに生息する。だが、この地域を取り囲む山々が気候に影響を及ぼしているため、近い距離の間にも、植生には著しい違いがある。

「北部太平洋沿岸地域」の定義は、主に自然環境に基づいている。ごく簡単に言うと、ここは海洋と険しい地形の影響を強く受ける地域である。降水量は多く、高い湿度を好む植物が海岸近くに生息する。だが、この地域を取り囲む山々が気候に影響を及ぼしているため、近い距離の間にも、植生には著しい違いがある。

米国で平均年間降水量が最も多いのは「太平洋岸北西地域」である。平均降水量が1,900ミリメートルを超えるのは普通で、ワシントン州北西部のオリンピック山脈の西側斜面では、その2倍にもなる。冬期には、ほぼ常に雲が垂れ込めている。

北太平洋は、湿気を多く含む巨大な気団がよく発生する地域である。この気団は移動するにつれ、卓越風によって南と東に押し流され、米太平洋沿岸地域に向かう。夏にはカリフォルニア沖に、冬にはメキシコ北西部沖に高気圧があるため、この海洋気団の多くは、それ以上南に移動することができない。かくして気団が含む水分のほとんどは「北部太平洋沿岸地域」で雨になる。多くの場所で冬の降水量は夏よりも多いが、季節による変動が最も激しいのはこの地域の南端部である。オレゴン州南部とカリフォルニア州北部の沿岸では、7月と8月の降水量が100ミリメートル未満で、12月から2月の10分の1しかない。

この地域は概して降水量が多いが、かなりの部分が半乾燥地域である。ワシントン州のピュージェット湾周辺では、年間降水量がわずか600ミリメートルしかない。降水が激しい雷雨の形になることはほとんどなく、濃い霧のような、穏やかな小雨がよく降るのが典型である。激しい雨はそのまま流れ去るのが普通だが、ここではそうならないため、結果的に植物は、水分を最大限に利用することができる。

海岸沿いで降水量が多く、地理的に近いのに気候が大きく異なるという、2つの現象を生んでいる最大の要因は、この地域の山々である。太平洋気団が陸上を東や南東方向へ進むと、「北部太平洋沿岸地域」に連なる山脈に突き当たって上昇する。空気は上昇すると冷えて水分含有量が減り、結果として雨が降る、という訳である。

オレゴン州南部・中部からカナダのブリティッシュコロンビア南西部までの一帯には、コースト山脈の背後に、オレゴン州のウィラメットバレーやワシントン州のピュージェット湾低地などの低い土地が控えている。東に向かう気団がこの低地を下降すると、暖まって水分含有量が増す。その空気にさらに水分が加わることはないため、ほとんど降水は起きない。

低地の東には、カスケード山脈という、南北に連なる2つ目の山脈がある。ワシントン州にあるレーニア山は標高が4,390メートルで、ほかにも2,750メートルから3,650メートル級の山々が多数ある。カスケード山脈の降水は冬期になると雪に変わるため、ここは米国で最も降雪量が多い地域となっている。

最後に、カスケード山脈のさらに東のワシントン州内陸部で、気団は再び下降して暖まる。空気中に残っているわずかな水分はそのまま維持されるため、ワシントン州東部の大部分の年間平均降水量は、300ミリメートルに満たない。

こうした山-谷-山の繰り返しで構成される一帯の南と北では、2つの山脈が合流して、山脈を隔てている谷が消滅する。最も降水量が多い地域は、降水と曇り空が絶えることがないアラスカ州の「パンハンドル地帯」(訳注=パンハンドルはフライパンの柄。カナダ沿岸部に細長く延びている部分)を含む北部沿岸部沿いの一帯である。アラスカ州北部や、「パンハンドル」西側の沿岸地域に来ると、平均降水量は急激に低下する。同州中央部の南向きの沿岸部のほとんどは、年間平均降水量が1,000ミリメートルから2,000ミリメートルである。

この地域の海洋性の立地は、雨をもたらすほかにも、気温の変化を緩やかにする効果を持つ。夏は涼しく、冬は驚くほど暖かいが、湿気が多いために風が冷たく感じられ、気温の割に快適とは言えない。

気団が季節移動するということは、この地域の沿岸部で頻繁に強風の吹く期間があることを意味する。冬の荒天期には、風速が時速125キロメートルを超えることも珍しくない。沿岸部の山脈がある程度風を防ぎ、概して夏には風も和らぐが、その夏でも、この地域の東部まで強風が吹くことがある。そうなると、火災の危険が増す。

「太平洋岸北西部」では、天気が晴れると、接する山々の峰を、ほとんどどこでも見渡すことができる。この地域の最北端にあるマッキンリー山は、標高6,200メートルの北米最高峰である。オレゴン州では、標高およそ1,200メートルに及ぶコースト山脈の山々が、ほぼ途切れずに続いている。一方、ワシントン州に入ると、山脈は途切れがちになり、コロンビア川やチヘーリス川などの下線が山と山の間を抜けて流れている。ワシントン州内では、コースト山脈の標高が300メートルを超えることはほとんどない。

カリフォルニア州北部とオレゴン州南部にまたがるクラマス山脈の地形は雑然としており、一定のパターンがほとんど見られない。ここは岩だらけで荒れ果てた、誰も住まない不毛の土地である。

オレゴン州の低地は、東のカスケード山脈が隆起したのと同時期にこの地域が沈下して形成された地溝の一部である。この地溝は、カナダのバンクーバー島をブリティッシュコロンビア州のほかの地域と隔てる海峡となって北方に続き、さらにアラスカ州の「パンハンドル」地域を形成する島々の間を通っている。これによって、はるか北のジュノーまで続く内陸航路が作られている。

さらに内陸では、クラマス山地から北へカスケード山脈が延び、ブリティッシュコロンビア州の南部まで続いている。これらの山脈のうち南の部分は、浸食を受けた標高の高い高原に火山の山頂が連なる地形となっている。全米で数少ない有史時代の活火山の1つであるカリフォルニア州のラッセン山と、オレゴン州のフッド山までの山々が、それを取り巻く高原から屹立している光景は、特に素晴らしい。カスケード山脈の北部はもっと険しく、長年、人口が多いピュージェット湾近くの低地から東への移動を妨げる大きな障害になってきた。ここでは、レーニア山を代表とする死火山が最も高い標高を誇り、くっきりとした峰を見せている。

アラスカ州の「パンハンドル」地域を過ぎ、氷河で覆われた巨大なセントエライアス山脈を越えると、山脈はアラスカ州南部で分岐する。コースト山脈、特にチューガッチ山地とキーナイ山脈は、東から西に向かうにつれて標高が低くなる。内陸にあるアラスカ山脈の方が標高は高く、途切れることも少ない。クック湾の奥に位置する広大な低地は、アラスカ山脈を貫く渓谷の南側にある。ここにはアラスカ州内では文句なしに最大の都市であるアンカレッジ(1993年の推定人口226,000人)が良港を囲むように位置しており、内陸部に通じる交通の便に恵まれている。

アラスカの州都であるジュノーは、「パンハンドル」地域の狭い沿岸低地にあり、州のほかの地域への輸送手段は空路と水路に限られている。この都市から車を運転して行ける最も遠い距離は約15キロメートルである。アラスカ州が「パンハンドル」の森林やサケ漁から富を得ていた時代や、スカグウェー経由のカナダ・ユーコン準州の金鉱地への交通の便が考慮すべき条件だった時代には、ここジュノーに州都を構えるのは妥当だった。しかし州の経済が変化して、ほかの資源の重要性が増すと、「パンハンドル」地域は活気をなくしていった。アラスカ州中部のフェアバンクス(1989年の推定人口32,300人)や州の南部へのアクセスがいいアンカレッジでは、人口増加率がジュノーを上回った。1989年のジュノーの人口はまだ29,000人に満たなかった。

植生に関しては、クラマス山地には立派なアカスギがある。ワシントン州とオレゴン州にはベイマツ、ベイツガ、ベイスギがある。そしてアラスカ半島にはベイトウヒが見られる。ここは単なる森林地帯ではなく、空に向かってまっすぐに伸びる高木が、美しい広がりを見せている土地である。

もっと乾燥した低地の場合、例えば、ウィラメットバレーの通常の植生はプレーリーグラスで、カスケード山脈の東側の土地では草と砂漠の低木となっている。これらの低地と、高木限界より高度が高いツンドラ地帯の2カ所を除けば、「太平洋岸北西部」は、すべて森林に覆われているか、もしくは覆われていた。降水量が多く、冬が温暖であるため、樹木の成長が促進される。林業は長年、この地域の経済活動の主流だった。今日でも、パルプや紙製品用の木材は米国南東部の方が生産量は多いが、材木の生産では「北部太平洋沿岸部」に勝る地域はない。

「北部太平洋沿岸地域」は、極地を例外とすれば、ヨーロッパ人による探査が最も遅かった海岸地帯である。ヴィトゥス・ベーリングは1740年以前から、アラスカ沿岸部はロシア領だと主張していた。その後1778年になって、ジェームズ・クック船長がオレゴンからアラスカ南東部までの沿岸を航海した。1805年、探検家メリウェザー・ルイスとウィリアム・クラークが、カスケード山脈を横断してコロンビア川の河口にたどり着いたが、フィラデルフィアとニューヨーク市(いずれもそれぞれ人口約75,000人)が、米国最大の都市の地位を競っていたのが、ちょうどその頃だった。米国人開拓者たちが「オレゴン街道(Oregon Trail)」を通ってウィラメットバレーへの移動を開始した1840年代半ばまでに、ニューヨークの人口は急増し、50万人に近づいていた。

この地域は、ヨーロッパ人がやってくる前も、人口は比較的多かった。穏やかな環境だったため、1年を通じて食料は豊富だった。シカ、ベリー類、根菜類、貝類、そして特にサケがこの地域の自然の恵みであり、その量は無尽蔵のように思われた。アメリカ・インディアンたちはこれを利用して狩猟・採集の経済活動を行い、食用作物は栽培しなかった。彼等は沿岸部に集中していた。多数の民族グループに分かれて、沿岸部にある個別の谷間に居住していたが、その場所は狭いことが多かった。ベイスギの厚板で大きくて立派な家を建設し、同じ木材で作った丸木舟で海へ出かけた。

ヨーロッパ人がこの沿岸部に到着すると、ほとんどの場所で、インディアンはどこかに消えてしまったように見えた。各グループは非常に孤立した状態にあったため、組織的な抵抗は不可能だった。それぞれの少数部族は黙って場所を明け渡し、ヨーロッパ人の入植にほとんど影響を及ぼさなかった。今日では、南部に残っているインディアンはほとんどいない。ここより北のアラスカ州の「パンハンドル」地域では、今でもインディアンが有力な少数民族グループを形成している。

沿岸部で最初に村落を築いたヨーロッパ人はロシア人だった。容易に搾取できる富を探して、18世紀末にやってきた。その富とは毛皮だった。ロシア人は交易所や伝道所をアラスカ州南東部に集中的に作ったが、その一部は遠くカリフォルニア州北部まで及んだ。開拓地では食料を自給できたことがなく、遠く離れて分散したこれらの入植地を維持する費用は、たいてい毛皮の売上による収入を上まわった。ロシアはこの植民地を米国へ売却しようと何度か試み、最終的に1867年、720万ドルの価格で売却に合意した。

19世紀初め、ハドソン湾会社が毛皮取引事業をコロンビア川流域に移した。この会社は、1830年代末に米国人宣教師と開拓者がミズーリからオレゴン街道を越える長い旅を始めるまで、「太平洋岸北西部」で最も大きな影響力を持っていた。新たな米国人開拓者は、ほとんどがウィラメットバレーに移住した。その数はたちまちのうちに、北西部全体を合わせても小さな英国系住民の人口を上まわった。

オレゴン州とワシントン州はその後発展を遂げることになるが、そこで決定的な役割を果たしたのは鉄道だった。1883年にノーザン・パシフィック鉄道がシアトルまで開通した。その10年後には、グレート・ノーザン鉄道が完成した。それまでこの地域は、南米の南端を経由して米国東部やヨーロッパの市場へ向かう海上輸送に大きく依存していたが、それも終わりを告げた。

今日では、この大自然に恵まれた地域にも、米国のほかの地域と同様に、都市人口がある。ワシントン州シアトルとオレゴン州ポートランドの大都市圏には、100万人以上の人々が住んでいる。

シアトルは19世紀後半のブーム時期以降、一貫して「北部太平洋沿岸地域」の最大の都市である。製材の中心地として作られ、大陸横断鉄道と結びついた時から、地域で最大の地位を占め始めた。1920年代からは、航空機メーカーのボーイング社の本拠地となり、世界最大の「企業の町」と呼ばれている。このほか同市には3,500の製造業があり、セメント、陶土、釣り具、小麦粉、金属製品、繊維製品、食品などを生産している。

シアトル市の中心部は、西側でピュージェット湾、東側でワシントン湖に接する狭い地峡に押し込まれた形になっている。ここは美しい街である。住宅は、沢山の丘の上や、並木道が続く快適な街区に分散しており、どこからでも山や海の景色を楽しむことができる。

ポートランドは、この地域の中では古い都市だが、ほかのたいていの地域の都市よりは新しい。シアトルと比べると、ポートランドの経済は多様化している。また、コロンビア川の渓谷が東へ向かう低地ルートになっているため、内陸部との関係も密接である。例えば、ポートランドはワシントン州東部から運ばれる穀物の主要積み換え地点であり、木材製品と食品加工がこの地域の製造業経済の主な活動である。ポートランドは海岸からおよそ160キロメートル内陸にあるが、コロンビア川下流は航行が可能なので、海洋港としてシアトルと張り合う関係にある。

多くの意味で、「北部太平洋沿岸地域」の経済構造は、基本材の生産と、国内のほかの主要市場からの孤立という2つの条件に支配されている。この地域では、特に、木材など需要の多い製品をずっと生産してきた。しかし、輸送費がかさむため、生産者が製品の市場価格を手頃な水準に抑えるのは難しかった。その結果、市場地域がもっと近くて費用も安いほかの供給地域に目を向けたため、「北部太平洋沿岸地域」の農産物の多くは、域外ではなく、地元市場向けに生産されている。

オレゴン州にある広大なウィラメットバレーは、この地域の沿岸近くにある、文句なしに最大の農業地域である。ここの土地では1世紀以上にわたり耕作が行われており、農家は裕福で基盤が安定している。大部分の農地では飼料作物が栽培されていて、多くの農家はいまでも秋になると野焼きをする習慣を守っている。そのため数週間も、盆地の大部分が厚い煙に覆われてしまう。

ウィラメットバレーで生産される乳製品は、やはりほとんどが地元市場向けに生産され、地域農業に最も貢献している。特産物の中で最も重要なのはおそらくイチゴだろう。そのほかホップ、芝生の種子、サクランボ、スペアミントなどの特産物も、この地域の気候にうってつけである。地元のワイン産業を支えるブドウの生産も近年、増加している。

ワシントン州のピュージェット湾低地は、もう1つの重要な酪農地帯である。ここでも特産物が栽培されており、エンドウマメの生産高が一番多い。エンドウマメは急速冷凍されて全米の市場に出荷される。この寒冷地方の作物は、地域の気候に特に適合している。

ワシントン州のカスケード山脈の東側に見られる農業の景観は、また異なっている。この地域の大部分は半乾燥気候であり、沿岸部や山間部に広がる常緑樹の代わりに、草や砂漠低木が生えている。この地域はコロンビア高原と呼ばれているが、高原特有の平坦さはほとんどない。この地域の大部分はうねうねと続く丘陵で構成されている。ワシントン州中部のその他の地域では、「クーリー」と呼ばれる切り立った枯れ谷で地形が分断されている。この地域は更新世の氷河の後退期に、氷河が融解して生じた洪水によって溝(channel)が刻まれた溶岩の厚い層で覆われている。そして、かさぶた(scab)状の溶岩の小山が地表に点在していることから、それにふさわしく、「溝のあるかさぶた状土(channeled scabland)」と呼ばれている。

オレゴンとワシントンの州境に沿って、ワシントン州東部の大部分を横断するコロンビア高原のこの部分は、「太平洋岸北西部」で最も重要な主要農業地域と言える。

ワシントン州東部から中央部にかけての丘陵地方は「パルース(Palouse)」と呼ばれており、年間降水量はほかの内陸部よりもいくらか多くて350ミリメートルから650ミリメートルである。この地域の主要作物は小麦で、春小麦と冬小麦の両方を栽培している。小麦は通常、畑ごとに1年おきに栽培する。畑は一応耕すが、1年間は何も植えないようにする。こうすると蒸発散が遅れ、土壌の水分が増加する。「パルース」の大規模小麦農場は機械化が進んでおり、生産性も高い。ここで生産される小麦のほとんどは、ポートランド経由でアジアへ輸出される。

ここ数十年、灌漑がこの地域の農業で大きな役割を果たしてきた。2つの大規模灌漑地域が開発されている。カスケード山脈から東へ向かって流れる多数の川の水が、比較的狭い谷間の土地の灌漑に利用されている。その結果、この地域は米国有数のリンゴ産地となった。

コロンビア川では、スポーカンの北西にあるグランドクーリーに、主として水力発電により電力を行うためのダムが建設された。また、それによってワシントン州の南部・中央部に大量の灌漑用水を提供している。1950年末にこの水が利用できるようになったおかげで、この地域の作付面積は著しく増加した。主な農産物には、テンサイ、ジャガイモ、アルファルファ、乾燥マメなどがある。

ワシントン、カリフォルニア、オレゴンの3州は、米国で伐採される木材の半分以上を供給している。またワシントン州は「深南部」のジョージア州と、パルプと紙の生産で首位を争っている。林業は「北部太平洋沿岸地域」の最初の主要産業だったが、その豊かな山林が全米で重要になったのは20世紀に入ってしばらくたってからだった。輸送施設に改良が加えられ、また東部の多くの森林が過剰伐採で破壊されたという背景から、この地域の森林が製材に使われるようになったのである。

ベイマツ(住宅の構造材として、また床、ドア、合板用として最も重要である)がこの地域の主要製材用樹木であることに間違いはないが、各地区には利用可能な様々な樹木が生えている。例えば、カリフォルニア州北部では、アカスギが地域的に重要である。ベイスギはオレゴン州以北の地域で広く伐採されている。

大きな樹木が多いことに加え、市場まで距離が離れていることから、伐採事業は大規模になりがちである。例えば、米国のある大手木材会社は、ワシントン州に69万ヘクタールもの土地を所有し、同州最大の民間土地所有者になっている。ワシントン州の大部分と、オレゴン州全域およびカリフォルニア州北部の土地の大半は政府所有である。政府所有の土地で民間企業が行う伐採事業が、木材の生産全体で大きな役割を果たしている。効果的な売り込み活動によって、この地域の木材製品は米国のあらゆる市場に進出することが可能になった。

「北部太平洋沿岸地域」では、降水量が豊富で地形が険しいため、水力発電の潜在能力は国内でほかに並ぶ地域がないほど大きい。オレゴン州とワシントン州だけで、潜在発電能力は全米の40%にのぼる。特に、ミシシッピ川より流量が多く、また米国とカナダの国境から海まで1,200キロメートル流れる間に300メートル近い落差があるコロンビア川は、電力開発関係者にとって、まことにうれしい存在である。

1933年に操業を開始した、この地域最大のグランドクーリー・ダムは、コロンビア川に最初に建設されたダムである。その後10カ所以上ものダムが下流にできた。カナダのブリティッシュコロンビア州と米国は、安定した発電量を確保するために、流量の多い時には水を貯蔵し、少ない時には水を放出するダムを、さらに3カ所、カナダ側に建設することで合意した。

これらの開発により、「北部太平洋沿岸地域」には安価な電力が供給されるようになった。そして、この安価な電力に引きつけられて、大量に電力を消費する製造業者がこの地域にやってきた。代表的なのはアルミ溶解産業である。

林業と漁業は一時期、この地域の経済の屋台骨だった。18世紀末から19世紀半ばまでの期間には、多数の捕鯨船が北太平洋の冷たい海に集まってきたものである。しかし乱獲により、北太平洋のクジラの数は、昔の水準に比べると見る影もないほど減ってしまった。

ヨーロッパ人の入植前、サケは沿岸部族の主要な食料源の一つだった。そして今でも、この地域で捕獲量が最も多い魚である。サケは海から川をさかのぼって移動し、真水で産卵する。何年も前には、産卵のために川を遡上するサケが川を埋め尽くし、川岸の人々はたくさんのサケを簡単に捕獲することができた。

サケの漁獲高は、過去50年間で大きく減少し、今ではかつての水準の半分以下である。サケはほとんどがアラスカの沖合で捕獲される。この地域の川がダムによってせき止められたため、従来の産卵場所のうち、特にコロンビア川上流とその支流に近づくことができなくなった。規模の小さなダムには、魚梯(ぎょてい=魚ばしご)が建設されている。これは、魚が上の段にジャンプして、ダムを迂回できるようにするための、緩やかな送水階段である。だが、大規模なダムでは使えないため、スネーク川とその支流のほぼすべてと、グランドクーリーより上にあるコロンビア川の全支流では、サケが上ることができない。

アラスカの南部沿岸部は明らかに「北部太平洋沿岸地域」の一部だが、この地域のほかの部分とは分けて眺めなければならない。アラスカ州と、北米大陸の人口が多い地域とを結ぶ鉄道はない。未舗装の部分もある1本の長い高速道路だけが、カナダの内陸部を経由して、アラスカ南部の沿岸部と米国のその他の地域とを結んでいる。沿岸部に山脈があるため、アラスカ州南東部の「パンハンドル」地域に住む人々は、ほとんど数百メートルを越えない幅の、狭い海岸線沿いの地域に押し込められている。この一帯は、外界との連絡手段を航空機と船に頼っているため、孤立感や、全米の動きからの疎外感を、この北太平洋沿岸地域のほかの地区よりも強く感じている。さらに、物不足や高い輸送コストによって物価が高い経済になっている。

アラスカの経済は鉱物、製材、漁業に大きく依存していると、多くの人が信じている。しかし、実際には、この州内の圧倒的な雇用者は、連邦政府、中でも国防総省である。アラスカ州のノーススロープにおける石油開発ブームでさえも、経済の政府依存という状況を解消してくれず、わずかに修正したにとどまっている。

*上記の日本語文書は参考のための仮翻訳で、正文は英文です。

The North Pacific Coast

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, An Outline of American Geography.)

The North Pacific Coast

By Stephen S. Birdsall and John Florin

Cold, clear mountain streams tumble down rock-strewn courses. The destination: a rugged, unused coastline where precipitous, fog-enshrouded cliffs rise out of pounding surf. Mountains are visible in the distance – lofty, majestic, covered with snow. Tall needleleaf evergreens cover the land between with a mantle of green. Cities, where they exist, give the impression that they are new. This is America's North Pacific Coast, or more popularly, the Pacific Northwest – the coastal zone that stretches from northern California through coastal Canada to southern Alaska.

An important element of its regional character is the North Pacific Coast's relative isolation from the rest of America. Less than 3 percent of the American population lives there. Populated sections of the region are separated from the other principal population centers by substantial distances of arid or mountainous terrain. Residents of the region often view this isolation as positive, a geographic buffer against the rest of the world. Economically, however, it has been a hindrance. High transportation costs inflate the price of Pacific Northwest products in distant eastern markets and discourage some manufacturers from locating in the region.

THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

The North Pacific Coast is defined primarily on the basis of its physical environment. Stated very simply, it is a region strongly subject to maritime influence and rugged terrain. Precipitation is high, and vegetation associated with heavy moisture is located near the coast but with marked variation over short distances because of the influence of surrounding mountains on the region's climate.

The greatest average annual precipitation in the United States is found in the Pacific Northwest. Averages above 190 centimeters are common, and averages are double that amount on the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains in northwestern Washington. During the winter, the cloud cover is almost constant.

The northern Pacific Ocean is a spawning ground for great masses of moisture-laden air. As these air masses move, they are pushed south and east by the prevailing winds onto America's Pacific shores. A high-pressure system located off the coast of California in summer and off northwestern Mexico in winter prevents many of these maritime air masses from drifting farther southward and ensures that most of their moisture falls over the North Pacific Coast. Winter precipitation amounts are everywhere higher than summer levels, but the seasonal difference is more marked on the southern margin of the region. The coast of southern Oregon and northern California receives less than 10 centimeters of precipitation during the summer months of July and August, only one-tenth of the amount that falls there between December and February.

Although this area has generally high precipitation, considerable portions are semiarid. Parts of the borderlands of Puget Sound in Washington receive only about 60 centimeters of precipitation annually. Precipitation seldom falls in the form of heavy thundershowers; more typical is a gentle, light, frequent rain that feels like a heavy mist. One consequence is that runoff, so normal in heavy rains, is lessened, and vegetation can make maximum use of the moisture.

The region's mountains are the main reason for both the high precipitation along the coast and the substantial climatic variations that exist in close proximity. As a Pacific air mass passes over land moving eastward and southeastward, it strikes the mountain ranges that line the North Pacific Coast and is forced to rise. As the air rises, it cools, and its moisture-carrying capacity is reduced, resulting in precipitation.

Along a belt extending from south-central Oregon to southwestern British Columbia in Canada, the Coast Ranges are backed by a trough of low-lying land, including the Willamette Valley in Oregon and the Puget Sound lowland in Washington. As the east-moving air descends into these lowlands it warms, and its moisture-carrying capacity is increased. Because additional moisture is not introduced into the air, little precipitation occurs.

To the east of the lowland is a second north-south trending range of mountains called the Cascades. Mount Rainier in Washington has an elevation of 4,390 meters, and many peaks are between 2,750 and 3,650 meters high. Winter precipitation in the mountains falls in the form of snow, making this the snowiest portion of the country.

Finally, in the eastern extension of the region beyond the Cascades in interior Washington, air masses again descend and warm. The little moisture that remains in the air is retained, and most of eastern Washington averages less than 30 centimeters of precipitation yearly.

South and north of this mountain-valley-mountain system, the mountain ranges merge and the separating valley disappears. Heaviest precipitation amounts are concentrated in a single band along the northern coast, including Alaska's "Panhandle," which is dominated by moisture and cloudiness. Average precipitation levels drop sharply along the coast in Alaska north and west of the Panhandle; most of the southward-facing coast of central Alaska averages 100 to 200 centimeters annually.

In addition to bringing rain, the region's maritime location provides a moderate temperature regime. Summers are cool. Winters are surprisingly warm, although the dampness means that the air can feel raw and less comfortable than the thermometer might suggest.

The seasonal movement of air masses means frequent periods of high winds along the region's coastal margin. It is not uncommon during the winter months for winds to exceed 125 kilometers per hour during the stormier periods. Although the coastal mountains provide some protection and winds are generally lower in the summer, high winds can reach the eastern portions of the region even in the summer. When they do, the danger of fire is worsened.

Few places in the Pacific Northwest do not offer a view of neighboring mountain peaks when the weather is clear. Mount McKinley at the region's northern extremity is, at 6,200 meters, the highest in North America. The peaks of the Coast Range of Oregon are fairly continuous in that state, with elevations reaching about 1,200 meters. In Washington they are discontinuous, with several rivers, notably the Columbia and the Chehalis, cutting pathways across them. Coast Range elevations in Washington are seldom above 300 meters.

The Klamath Mountains of northern California and southern Oregon offer a jumbled topography. Little pattern is apparent in the terrain. This is a wild, rugged, empty area.

The lowlands of Oregon are part of a structural trough that was created when that area sank at the same time that the Cascades to the east were elevated. This trough extends northward in the form of straits separating Canada's Vancouver Island from the rest of British Columbia, then passes through the complex of islands that line the Alaska Panhandle and provides the Inside Passage north as far as Juneau.

Farther inland, the Cascades extend from the Klamath Mountains northward into southern British Columbia. The southern section of these mountains appears as a high, eroded plateau topped by a line of volcanic peaks. Between Mount Lassen in California (one of the few volcanoes in the United States to have been active in historic time) and Mount Hood in Oregon, these peaks are especially splendid in their isolation above the surrounding plateaus. The northern Cascades are more rugged and have long proved a difficult barrier to movement eastward from the populous Puget Sound lowland. Here, extinct volcanoes, most notably Mount Rainier, provide the highest elevations and best defined peaks.

Beyond the Alaska Panhandle and the massive, glacier-covered St. Elias Mountains, the mountains divide in southern Alaska. The Coast Ranges, notably the Chugach and Kenai Mountains, decline in elevation from east to west. The interior mountains, the Alaska Range, are much higher and more continuous. A large lowland at the head of Cook Inlet is south of a gap through the Alaska Range, and here Anchorage, easily the largest city in Alaska (with an estimated population of 226,000 in 1993), is located around its good harbor and with easy connection to the interior.

Juneau, the capital of Alaska, is located on a narrow coastal lowland on the Panhandle; its only transportation connections to the rest of the state are by air or water. The farthest one can drive from town is about 15 kilometers. This location for the capital was reasonable when Alaska's wealth was in the Panhandle's forests and salmon fisheries and when access to the Yukon gold fields through Skagway was a consideration. As the state's economy changed and other resources became more important, the Panhandle languished. Fairbanks (with an estimated population of 32,300 in 1989), in central Alaska, and Anchorage, which is accessible to the southern portion of the state, outstripped Juneau in population growth; the capital city still had fewer than 29,000 people in 1989.

In terms of vegetation, there are magnificent redwood stands in the Klamath Mountains; Douglas fir, hemlock, and red cedar in Washington and Oregon; and Sitka spruce on the Alaska peninsula. This is a land not just of forest, but of beautiful expanses of tall trees reaching straight for the sky.

Except for the drier lowlands, where the normal vegetation of the Willamette Valley is prairie grass and that of the land east of the Cascades a mix of grass and desert shrub, and except for the tundra above the tree line, all of the Pacific Northwest is, or was, covered by forest. Tree growth is encouraged by plentiful moisture and moderate winter temperatures. Forest products were long the economic mainstay of the region. Even today, while the southeastern United States produces more wood for pulp and paper products, no other part of the country provides as much lumber as the North Pacific Coast.

PATTERNS OF HUMAN OCCUPATION

No other coastline, except for the polar areas, was explored by Europeans as late as was the North Pacific Coast. Vitus Bering had claimed the Alaska coast for Russia by 1740, but it was not until 1778 that Captain James Cook sailed the coast from Oregon to southeastern Alaska. By the time explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark worked their way across the Cascades to the mouth of the Columbia River in 1805, Philadelphia and New York City, each with about 75,000 people, were vying for the title of the country's largest city. By the mid-1840s, when American settlers began traveling the Oregon Trail to the Willamette Valley, New York's population was fast approaching 500,000.

The pre-European population of the region was relatively large. The moderate environment provided a plentiful supply of food throughout the year. Deer, berries, roots, shellfish, and especially salmon represented a natural bonanza of food that seemed without limit. The American Indians responded to this with a hunting and gathering economy, and no food crop cultivation. Concentrated along the coast, they were divided into many distinct ethnic groups, each occupying their own, often small, coastal valley. They constructed large, impressive houses of red cedar planks and went to sea in dugout canoes made of the same wood.

Along most of this coast, the Indians seemed simply to melt away when Europeans arrived. Because their extreme isolation made organized opposition impossible, each small tribe succumbed quietly, making little impact on European settlement. Today, few Indians remain in the south. Farther north, the Indian population remains a substantial ethnic group in the Panhandle of Alaska.

Russians were the first Europeans to establish permanent settlements along the coast. They came late in the 18th century, motivated by the search for easily extracted riches. These riches proved to be furs, and the Russians established a series of trading posts and missions that were concentrated in southeastern Alaska but that extended as far south as northern California. The outposts never became self-sufficient in foodstuffs, and the cost of maintaining these scattered, distant sites usually exceeded the income from fur sales. Following several earlier Russian attempts to sell the colony to the United States, a $7.2 million sale price was finally agreed upon in 1867.

The Hudson's Bay Company moved its fur-trading operations into the Columbia River basin early in the 19th century. It was the dominant influence in the Pacific Northwest until the late 1830s, when American missionaries and settlers began the long journey across the Oregon Trail from Missouri. Most new American settlers moved into the Willamette Valley, but they quickly outnumbered the small British population of the entire Northwest.

The railroads were of key importance in the eventual growth of Oregon and Washington. In 1883, the Northern Pacific Railroad was completed to Seattle and was followed a decade later by the Great Northern. This ended the region's overwhelming dependence on oceanic shipment, which sailed via the southern tip of South America to the eastern United States and European markets.

Today, this land of the great outdoors, like nearly every other part of the United States, has an urban population. Both Seattle, Washington, and Portland, Oregon, have metropolitan area populations of more than 1 million people.

Seattle has been the largest city along the North Pacific Coast since the boom era of the late 19th century. Founded as a logging center, Seattle began to achieve regional dominance when it was linked to the transcontinental railroads. The city has been the home of the Boeing (aircraft) Company since the 1920s, and it has been called the world's largest company town. Other of the city's 3,500 manufacturers produce cement, clay, fishing supplies, flour, metal products, textiles, and food products.

Seattle's urban core is tucked onto a narrow isthmus bordered by Puget Sound on the west and Lake Washington on the east. It has a beautiful site, with views of mountains and water offered to the residents of its many hills and pleasant, scattered neighborhoods of tree-lined streets.

Portland is an old city by the standards of the region, new by most others. Its economy is more diversified than Seattle's, and its relations with the region's interior are closer because of the lowland routeway to the east provided by the valley of the Columbia River. Portland is a major transshipment point for grain from eastern Washington, for example, and wood products and food processing are principal activities of the local manufacturing economy. Portland, inland about 160 kilometers from the coast, nevertheless rivals Seattle as an ocean port because the lower Columbia River is navigable.

THE REGIONAL ECONOMY

In many ways, the economic structure of the North Pacific Coast is dominated by the production of staple products and by its isolation from major markets elsewhere in the country. The region has always contained a number of high-demand products, notably lumber and foodstuffs. However, movement costs reduced the ability of producers to get their products to market at reasonable cost. Consequently, market areas turned to other sources of supply that were nearer and less expensive, so that much of the North Pacific Coast's agricultural products are grown for the local market, not for export.

The broad Willamette Valley in Oregon is easily the largest agricultural area near the region's coast. The land has been cultivated for more than a century, and its farms are prosperous and well established. Much farmland is in forage crops, and many farmers still follow the practice of burning their fields in the fall – with the result that for a period of several weeks, large sections of the valley are covered by a layer of smoke.

Dairy products, also generated mostly for the local markets, are of greatest importance to the agriculture of the Willamette Valley; strawberries are perhaps the most important specialty crop. Other specialty crops also thrive in the valley's climate, including hops, grass for turf seed, cherries, and spearmint. Even grape production, supporting a local wine industry, has increased in recent years.

The Puget Sound lowland in Washington is another important dairy area. Again, specialty crops are also grown, with peas leading the pack. Quick frozen and then shipped to markets throughout America, this cool-weather crop is particularly well adapted to the local climate.

The area east of the Cascades in Washington presents a different kind of agricultural landscape. Most of this area is semiarid, and grasses and desert shrubs replace the majestic evergreens of the coast and mountains. Although called the Columbia Plateau, the area has little of the characteristic flatness one expects of a plateau. Much of the area consists of rolling hills. Elsewhere in central Washington, the landscape has been cut by steep-sided dry canyons called coulees. That section – properly called "the channeled scablands" because lava pockets dot the surface with scab-like knolls – is covered by a deep blanket of lava flows eroded by the floods from glacial melt during the Pleistocene ice retreat.

That portion of the Columbia Plateau along the Oregon-Washington border and across much of eastern Washington is a substantial farming area, easily the most important in the Pacific Northwest.

The hilly country of east-central Washington, called the Palouse, averages between 35 and 65 centimeters of precipitation annually, somewhat more than other parts of the interior. Wheat is the primary crop of the area, with both spring and winter varieties grown. Wheat is normally planted on a given field every other year; in alternate years, the land is plowed, but nothing is planted. This practice retards evapotranspiration and allows soil moisture to increase. The large wheat farms of the Palouse are heavily mechanized and highly productive. Most of the product is exported through Portland to Asia.

Irrigation has played a major role in the area's agriculture in recent decades. Two major irrigated areas have been developed. The water from a number of streams flowing eastward out of the Cascades is used to irrigate their relatively narrow valleys. The result is one of the country's most famous apple-producing areas.

The Columbia River, at Grand Coulee northwest of Spokane, was dammed primarily to provide hydroelectric power. It also made available large amounts of irrigation water to south-central Washington. After these waters became available in the late 1950s, crop acreage in the area expanded considerably in response. Major agricultural products include sugar beets, potatoes, alfalfa, and dry beans.

Washington, California, and Oregon together provide more than half of all timber cut in the United States, and Washington vies for the lead (with the Deep South state of Georgia) in pulp and paper production. Although forestry was the first major industry in the North Pacific Coast, its rich forest did not become nationally important until well into the 20th century, when improved transportation facilities, coupled with the destructive overcutting of many eastern forests, opened the region's woods to lumbering.

Douglas fir (of prime importance as structural supports for houses and for flooring, doors, and plywood) is easily the major lumber tree of the region, although each section has its own mix of trees to harvest. In northern California, for example, redwoods remain locally important; the western red cedar is also widely cut in the area from Oregon northward.

The large size of many of the trees plus the distances to market tends to encourage large-scale logging operations. One major U.S. lumber company, for example, owns some 690,000 hectares of land in Washington, making it the state's largest private landowner. A substantial part of Washington and a majority of all land in Oregon and northern California is government owned. Private logging on government land plays a large role in overall production. Effective marketing has enabled lumber products of the region to penetrate all market areas of the country.

The plentiful precipitation and rugged topography of the North Pacific Coast provide a hydroelectric potential unmatched in the United States – 40 percent of the country's potential is contained in Oregon and Washington alone. The Columbia River, in particular, with a flow volume larger than that of the Mississippi River and a drop of nearly 300 meters during its 1,200-kilometer course from the U.S.-Canadian border to the sea, is a power developer's delight.

Begun in 1933 and still the region's largest, Grand Coulee Dam was the first dam constructed on the Columbia River. It was followed by no fewer than 10 dams downstream. British Columbia and the United States agreed to the construction in Canada of three additional dams that would store water during periods of heavy flow and then release the water when flow was low to guarantee consistent power generation.

These developments have provided inexpensive electricity for the North Pacific Coast. Inexpensive electrical power, in turn, has attracted manufacturers that are heavy power consumers; most notable is the aluminum-smelting industry.

Forestry and fishing at one time formed the backbone of the region's economy. Large numbers of whaling vessels were attracted to the cold waters of the North Pacific during the late 18th century and first half of the 19th century. Heavy overharvesting has reduced the North Pacific's whale population to a small fraction of former levels.

Salmon contributed a major part of the foodstuffs of the coastal tribes before the arrival of Europeans, and remains the principal fish caught throughout the region. Salmon migrate upstream from the ocean to spawn in freshwater. Years ago, their spawning runs filled the rivers, and massive catches were easily available to people on the banks.

The size of the salmon catch has declined greatly over the past five decades, and today it is less than half its former level. Most salmon are caught off the Alaska coast. When the region's streams were dammed, access to many traditional spawning grounds was blocked, especially on the upper Columbia and its tributaries. Fish ladders – a series of gradual water-carrying steps that allow fish to jump from level to level and thus bypass a dam – have been constructed around some of the smaller dams, but they do not work on the larger ones. As a consequence, nearly all of the Snake River and its tributaries, plus all of the branches of the Columbia above Grand Coulee, are closed to salmon.

ALASKA – A POLITICAL ISLAND

Coastal southern Alaska is clearly a part of the North Pacific Coast, but it must be viewed as somewhat separate from the rest of the region. No railroad connects Alaska with the more populated parts of the continent, and only a single, long highway, part of which remains unpaved, connects coastal southern Alaska through interior Canada to the rest of the United States. People in the Panhandle of southeastern Alaska are crowded by coastal mountains onto a narrow shoreline rarely more than a few hundred meters wide. This portion of the region looks to air and sea transportation for connection with the rest of the world, which leads to an even greater sense of detachment than might be typical of the rest of the region, a greater sense of separation from the activities of the rest of the country, and an economy of high prices resulting from scarcity and high transportation costs.

Many believe that the Alaskan economy is based heavily on minerals, lumbering, and fishing. In fact, the federal government, primarily the Department of Defense, is the dominant employer in the state. Even the petroleum development boom on the state's North Slope has only modified, not eliminated, this orientation.

[Stephen S. Birdsall is dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Michigan State University and is the co-author of four books and atlases, including Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada.]

[John Florin is chair of the geography department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Pennsylvania State University. His recent publications include Atlas of American Agriculture: The American Cornucopia with Richard Pillsbury and Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada with Stephen S. Birdsall.]