国務省出版物

米国の地理の概要 – 人の住まない内陸部

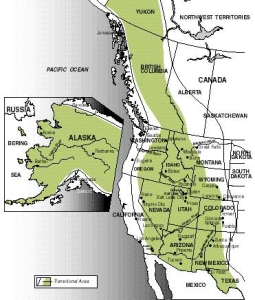

ロッキー山脈の東側の斜面から西のシエラネバダ山脈(カリフォルニア州)、太平洋北西部のカスケード山脈を経てアラスカまで、人口がまばらという点で米国最大の地域が広がっている。平均人口密度が低いことが、この地域を際立たせる最大の特徴である。実際には、この地域の地理を構成するその他の要素には場所によって大きな違いがみられる。岩だらけの土地が続き、そのあちこちに広い平らな部分を持つ高原が点在しているところもある。年間降水量も一定ではなく、アイダホ州北部では1250ミリメートルを超えるが、高原地方では250ミリメートルに満たない。この地域の住民はほとんどがヨーロッパ系だが、南部はヒスパニック系やアメリカン・インディアンの比率が高い。灌漑農業と牧畜が重要な地域もあれば、製材業、観光業、鉱業が経済活動の大部分を占める地域もある。

この広大な地域には、米国で最も風光明媚な場所がいくつかある。この地域に対して人間は局地的には重要な影響を及ぼしているが、自然環境の様々な素晴らしさを前にして、人間はすっかり影が薄くなっている。

東部出身の米国人は、激しい起伏がめったにない、ゆったりとした地形の土地に慣れている。たとえ山があっても、ふもとから頂上までの標高差が1,000メートルを超えることはほとんどない。対照的に、西部の内陸部では、1,000メートルを超えるほどの劇的な高低差がよくみられる。

東部出身の米国人は、激しい起伏がめったにない、ゆったりとした地形の土地に慣れている。たとえ山があっても、ふもとから頂上までの標高差が1,000メートルを超えることはほとんどない。対照的に、西部の内陸部では、1,000メートルを超えるほどの劇的な高低差がよくみられる。

この地域の自然地理的要素の2つ目は、土地の険しさである。米国東部では山のほとんどが丸みを帯び、同じ形をしているが、西部の山々は斜面が急でほぼ垂直になっており、その頂上の多くは、ぎざぎざの刃が空に突き出ているように見える。このような違いが生まれたのは、山の年齢も一因である。西部の山は、すべてとは言えないが、そのほとんどが東部よりもかなり若い。従って、土地の表面を滑らかにする浸食作用にさらされてきた期間がずっと短い。

地質年代の最も新しい時代である更新世に、山岳氷河で土壌が削られて、西部内陸部の地勢が出来上がった。いまも残る氷河の残骸を、この地域の一部で見ることができる。小さな氷河はアラスカ州南部の太平洋沿岸の山々にもっとも広く散在しているが、さらに南に下ってコロラド州のロッキー山脈中央部や、カリフォルニア州のシエラネバダ山脈でも見ることができる。

高山性の氷河は、標高が高い場所で形成され、氷のかさが増すに従って徐々に斜面を下って流れる。この移動する氷は、大きな侵食作用を起こす。この侵食パターンが十分長く続けば、両側がほぼ垂直で底面が比較的平らな、深いU字型の谷ができる。もし2つの氷河が並んで流れると、「アレート(山稜)」と呼ばれる小さなぎざぎざを特徴とする、狭い稜線ができる。シエラネバダ山脈のヨセミテ渓谷は、氷河で刻まれた典型的ともいえる渓谷であり、深さ2キロメートル近くにも達する。これは、この地域で最も多く写真に撮られている高山性氷河作用の事例といえるだろう。

「人の住まない内陸部(Empty Interior)」の大部分を占めるのは、山ではなく台地である。この地域の中で最も劇的な景観を誇る一帯は、ユタ州とアリゾナ州のコロラド川中流沿いにあるコロラド台地だろう。土地の起伏が構造的に大きく変化している場所もあるが、この地域の大部分の地下には、緩やかに傾斜する堆積岩が横たわっている。この地形的に大きな特徴は、この高原を横切って流れる「外来河川」(乾燥した環境に水という未知のもの、つまり外来のものを運び込むことから、このように呼ばれる)の侵食によって生まれた。そのうち最も重要なのがコロラド川とその支流である。この地域の環境を見れば、浸食作用を及ぼす要因として最も影響力が大きいのが河川であることはすぐわかる。従って、これらに加えて、地質学的に近い年代に、コロラド高原の広い範囲で著しい地質隆起が発生したことから、主に河川のすぐ脇に沿って、強度の下方侵食が発生した。こうして形成された渓谷は、米国有数の自然観光資源となっている。実際、アリゾナ州にあるコロラド川沿いのグランドキャニオンは、米国でもっともよく知られた自然の景勝地の1つである。グランドキャニオン国立公園では、所々で幅16キロメートル以上にもなる渓谷系が形成されている。さらに、このような堆積層の地形では、固い岩も柔らかい岩もあって浸食抵抗性が一定でないため、角張った急斜面や段丘の連なりが生まれ、この地域の特徴となっている。

コロラド台地を起点に、南はニューメキシコ州南部とアリゾナ州を横断し、西はカリフォルニア州のデスバレーとモハーベ砂漠まで、そして北はオレゴン州とアイダホ州まで続く地域を占めているのは、「盆地と山脈の地域」である。80あまりの広くて平らな盆地を持つこの広大な一帯は、通常は長さが120キロメートル未満で、南北の方向に一直線に連なる、高さがほぼ1,000~1,600メートルの山脈が、200以上も存在する。コロラド川流域の北と西の地域はほとんどが内地排水である。つまり河川は地域内で始まって地域内で終わり、海への出口はない。その結果、この地域には周辺の山脈が浸食を受けて発生した大量の堆積物が流れ込んだ。

更新世には、当時の湿潤な気候と、高山性氷河の氷解から生まれた湖が、この地域の大部分を占めていた。そのうち最大のボンネビル湖は、現在のユタ州北部にあり、面積は25,000平方キロメートルもあった。これらの湖のほとんどは、年間降水量の減少が河川の流量に影響し、消滅するか、面積がかなり小さくなってしまった。また、ネバダ州のピラミッド湖やユタ州のグレートソルトレークのように、今も残っている湖の多くは塩度が極めて高い。河川の流水は、溶解可能な塩分を常に少量ずつ吸収して運んでおり、通常はわずかとはいえ海の塩度を保つ役割を果たしている。しかし、この地域の湖は、川が流れ込んでくるばかりで、そこから海に流れ出る出口がないため、塩分濃度が高まることになった。面積が約5,000平方キロメートルの湖、グレートソルトレークは、ボンネビル湖の名残であり、今日では、その塩分濃度は海よりもずっと高くなっている。

「盆地と山脈の地域」の北にあるコロンビア台地は、溶岩流が徐々に蓄積されて出来上がった。周囲を山に囲まれていたため、厚さが平均3メートルから6メートルにもなる溶岩流が、繰り返し流れ込んでは蓄積されていき、場所によっては厚さ650メートルに達するところもある。この地域には、少数の小さな火山や噴石丘は点在しているが、この辺の火山活動が残した主な特徴は、かつての溶融物質が大量に流れ出た跡である。ここでも、河川の浸食作用で、深い急斜面の渓谷が作られている。

このように浸食による深い谷が所々にある高原が、ロッキー山脈と太平洋山岳地帯の間の地域を北上して、カナダのユーコン州まで続いている。アラスカ州中央部では、ユーコン川の集水域が、アラスカ山脈からブルックス山地に至る地域の大部分を占めている。表層物質は主に堆積岩である。

西部内陸部では、降水量と標高の間に、強い相関性がある。標高が低い地域は、概して乾燥している。通常は、山の斜面の中間地点あたりで最も降水量が多い。この地域の地表水は、ほとんどすべてを外来河川に頼っている。

地形、気温、降水量という3要素の相関関係によって、「人の住まない内陸部」全域の植生分布は、明白に標高で区分されている。最も標高が低い場所には、砂漠に生息する低木、主にヤマヨモギが生えている。はるか南の地域では、夏の終わりに、ある程度降水量が増加するため、ヤマヨモギと草地の両方がみられる。その他の場所では、ヤマヨモギと草地の両方が見られるのは、砂漠の低木地域より標高が高い場所だけである。ヤマヨモギ生育地よりも高い斜面を上ったところに低い方の樹木限界線があり、これより標高が高い場所では、樹木の成長に十分な量の雨が降る。森林が始まる地点は、草地と樹木が混在する移行地域である。ここにはピニョンマツ(松)やビャクシン(柏槇)の様な小型の樹木が生えている。標高が高くなると、これに代わって、ポンデローサマツ、コントルタマツ、ベイマツのような、より大きな樹木で構成される広大な森林が現れる。山がもっと高くなると、次第に亜高山性のモミ種のような小型の樹木に替わり、もうひとつ上の樹木限界線が現れる。この限界線より標高が上がると、強風が吹き、温度が下がり、生育期間も短くなるので、樹木は育たなくなり、やがて樹木の替わりにツンドラで覆われることになる。

「人の住まない内陸部」では、バイソン(バッファロー)、ワピチ(北米エルク=オオジカ)、プロングホーン(羚羊)、クマ、オジロジカ、七面鳥などの野生動物が増えている。

ネバダ州では、様々な政府機関が、すべて土地の90%近くを管理している。ほかの州ではこの比率は下がるものの、政府による土地の管理という基本パターンは、「人の住まない内陸部」のどこへ行っても見られる。

これほど広い土地が相変わらず政府の管理下にあるのは、驚くべきことではない。この地域とアラスカは、米国で相当数の人々が定住するようになった最後の地域である。土地のほとんどは農業利用できる見込みが全くなかったため、農業利用の振興を目的とした連邦政府の土地分配プログラムは意味がなかった。米国国勢調査局は1890年に、開拓辺境の終わりを宣言したが、この時点では、西部内陸部の大部分は未開拓の状態にあった。その後、製材業や鉱業といった農業以外の利害関係者が、民間の土地所有の拡大を要求し始めたが、そのころには、連邦政府は土地をほとんど無償で分配したプログラムの見直しを始めていた。

米国の国立公園としては、イエローストーン、グレーシャー、グランドキャニオンなどが有名だが、その多くが西部内陸部にある。しかし国立公園は、公有地全体の一部にすぎない。これら公有地を最も多く所有しているのは、米内務省土地管理局で、公有地を様々な方法で利用しており、うち放牧がもっとも重要である。同局はこの地域の灌漑・水力発電ダム建設でも主役を担ってきた。

米農務省林野部は、土地管理局に次いで多くの公有地を所有している連邦政府機関である。林野部は多目的の土地管理の中でも、従来から伐採と放牧に力を入れているが、土地のレクリエーション利用についてもその質と量を高めている。

「人の住まない内陸部」には、ほかに2つの用途があるが、この2つの用途をみると、この地域の歴史や、この土地の質と有用性に対する米国の考え方がわかる。まず、アメリカン・インディアン保護特別保留地の中でも最大級のものが、この地域、特にアリゾナ州北部とニューメキシコ州にある。また、米国最大の爆撃および射撃訓練場のほか、唯一の原子爆弾試験施設もこの地域にある。人口がまばらであり、その他に土地の需要があまりないからである。

19世紀の後半の数十年に、農業の辺境は西に移動したが、その際、西部内陸部の大部分はさっと通り過ぎてしまった。実際、鉱物資源、輸送手段、末日聖徒教会がなかったならば、この地を定住地として選ぶ人など、20世紀に入ってもほとんどいなかったことだろう。

一般的にはモルモン教として知られる末日聖徒教は、1830年にニューヨーク州北部で設立された。モルモン教会と信徒は、その教義が「特殊」と見られたため、繰り返し口汚く罵倒され、暴力も受けた。モルモン教徒は自分たちの宗教を実践する場所を求めて何度も移動した。そして多くの教徒が、独立したモルモン州の創設を目指して、徒歩で西部へと進んだのである。

西部の最初の居住地として彼等が選んだ場所は、ユタ州北部のワサッチ山脈とグレートソルトレークの間にひっそりと存在する、ワサッチ・バレーだった。ここがその後、ソルトレークシティとなる。ここは農業を始めるにはふさわしくない場所のように見えたに違いない。気候は乾燥しており、湖は塩度が高かったために役に立たず、風景は荒涼としていた。しかし、モルモン教徒はすぐさま農作業に着手し、集落は新たな入植者が来るにつれて拡大していった。出生率が高かったことも人口増の一因であった。彼等は、北は現在のオレゴン州とアイダホ州、南はカリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスに至るまでの土地に、「デゼレット(Deseret)」という名の独立国家を作ることを夢見ていた。そして、モルモン社会はソルトレークシティからずっと遠くへと広がっていった。

最終的には、「デゼレット」を作るというモルモン教徒の夢はついえた。カリフォルニア州とネバダ州で金が発見されると、アメリカ合衆国の拡張はモルモン地域を越えて進み、モルモン教徒は再び合衆国の支配下に入ってしまった。結局「デゼレット」は6つの州にまたがって分割されてしまったのである。

モルモン教徒は、西部内陸部での生活上の問題点に直面した最初の米国人だったが、その大部分を自分たちで解決した。中でも、灌漑の解決ほど重要なものはなかった。それより以前、米国人は広範囲に及ぶ灌漑を必要としておらず、多数の農業利用者のところまで、水を集めて運ぶために必要な技術と中央管理システムなど、ほとんどだれも知らなかったのである。モルモン教徒はワサッチ山脈の西の斜面に多数の貯水ダムを建設した。また、何キロメートルも続く運河を建設して、ダムの水を渓谷の下方にいる利用者まで運んだ。こうした努力の結果、今日では、渓谷の大部分が、農作物や樹木や芝生で覆われている。こうしたの初期の努力が、西部内陸部での灌漑ブームの火付け役となった。

モルモン教徒は、今でも西部内陸部に多大な影響を及ぼしている。この地域に住むおよそ1,100万人の住民のうち、150万人がモルモン教徒である。

灌漑と農業:「人の住まない内陸部」を流れる重要河川のうちのいくつかは、灌漑を筆頭とする様々な目的に多くの水が利用されている。1902年開墾法(Reclamation Act of 1902)の規定により、西部17州(アラスカとハワイを除く)におけるダム、運河、そして最終的には水力発電システムの建設を、連邦政府が支援することになった。今日では、このような連邦政府の支援プロジェクトから得られる水の80%以上が灌漑に利用されている土地の面積は、計400万ヘクタール以上に及ぶ。灌漑地のほとんどはカリフォルニア州にあるものの、大規模な灌漑プロジェクトは地域全体に散らばっている。

スネークリバー平原で100万ヘクタールに及ぶ土地が灌漑されたことによって、アイダホ州の土地の灌漑面積は、この地域が最大となった。これにより、アイダホ州は米国有数のジャガイモとテンサイの産地になった。コロンビアバレー開墾プロジェクトでは、ワシントン州中央部のグランドクーリー・ダムに蓄えられたコロンビア川の豊富な水を使って40万ヘクタールを優に超える土地の灌漑を行い、アルファルファ、テンサイ、ジャガイモなどの作物を生産している。ワサッチ渓谷の灌漑は、モルモン教徒が開拓を始めた最初の数十年以降、ほとんど進んでいない。ワサッチ渓谷にあるおよそ40万ヘクタールの灌漑地では、主にテンサイとアルファルファが生産されている。コロラド州の西部から中央部にかけてのコロラド川流域にあるグランドバレーでは、主にアルファルファとジャガイモが生産されているが、モモなどの果樹も重要である。ワシントン州では、コロンビア川の支流、特にヤキマ川とウェナチ川が、米国で最も有名なリンゴ産地に水を供給している。

これらの各地域が生産する作物の種類は限定されている。耕作期間が短いため、ほとんどの長期植付け作物は生産することができない。また、地元の需要が限られているため、乳製品や生鮮野菜も需要はごくわずかである。

さらに南の灌漑地域は、灌漑用水の不足に悩まされてきたものの、北の地域と比べて大きな利点が1つある。それは、耕作期間が長いことだ。カリフォルニア州のインペリアルバレーは、年間の無霜期間が300日を超え、米国有数の作物生産地となっている。米国の冬レタスの多くはこの地域が供給しており、ブドウや綿花、ウシの肥育飼料となるアルファルファも同様である。この地域ではウシを25万頭以上飼育している。新たに建設された発電施設は、地元で豊富に手に入る牛糞を燃料にしている。インペリアルバレーの耕作期間は二毛作ができるほど長いため、もちろん全体的な生産性の向上に貢献している。

カリフォルニア州のソルトン湖の北にあるコーチェラバレーでは、デーツ(ナツメヤシ)、ブドウ、グレープフルーツなどの作物を栽培している。コロラド川下流沿いのユマバレーでは、綿花、テンサイ、オレンジの生産が盛んである。アリゾナ州フェニックス近くのソルトリバーバレーでは、冬レタス、オレンジ、綿花が主要作物となっている。これら南の地域で栽培される作物は、ずっと北の作物と異なり、米国東部の主な市場地域にある農業の中心地との競争に直接さらされることは、ほとんどない。

輸送サービス:西部内陸部では、地域内の交通がほとんどないため、輸送網を広げる主な目的は、できるだけ速く、安いコストで地域を横断できるようにすることだった。従って、主要高速道路や鉄道路線は、そのほとんどが地域を東西に通り抜け、中西部の都市部から西海岸の都市部に至っている。

こうした輸送網の設計とは別に、この地域は横幅が広いため、ここを通過する人々へのサービスを目的とする施設を、多数建設する必要がある。この地域の町の多くは、鉄道のサービス・管理センターとして始まった。センターは、地域人口の多少にかかわらず、鉄道職員を必要とする場所にはどこにでも作られた。1940年代末に技術革新が始まると、現場で必要となる鉄道職員の数は減ったが、ガソリンスタンドや車の修理工場、モーテル、レストランなどでトラックや自動車で移動する人々にサービスを提供するための労働力の需要は、むしろその人口減少分を上回った。

都市部発展の初期には輸送サービスが重要な影響を及ぼしたが、大都市といえるようになった町については、通常、ほかにもその成長を支えてきた特質がある。例えば、人口が35万人を超えるワシントン州スポーカンは、同州の「内陸の帝国(Inland Empire)」第一の中心地である。この地域はワシントン州中心部を流れるコロンビア川に半分囲まれた地形が地理的境界線として定められており、昔から農業が盛んだった。人口およそ50万人のニューメキシコ州アルバカーキは、同州の中心に位置し、交通の便もよかったため、スポーカンと同じ役割を果たすようになった。アリゾナ州フェニックスは当初、農業の中心地として発展したが、米国人が暖かく乾燥した環境を求めてここに集まるようになって急速に成長した。現役引退後の人々にとっての中心地になったのに加え、製造業の中心地にもなり、電子機器産業などの、小型で付加価値の高い製品を製造する産業が、フェニックスの発展にとって特に重要な役割を果たしている。

ユタ州オグデンは、主要鉄道センターとして機能している都市であり、この地域の重要な鉄道センターの中でも、早くから発展した町だった。しかしここは、大都市にはならなかった。ユタ州の州都としての機能を発揮し、モルモン教の総本山としても君臨するソルトレークシティから、北へおよそ55キロメートルしか離れていないことがその要因である。

観光業:「人の住まない内陸部」の様々な景観は素晴らしい魅力に富んでおり、毎年、何百万人もの観光客を引き寄せている。大きな公園を訪れる人々は最初に、モーテルや軽食堂、土産物店、その他の地方色豊かな店が建ち並ぶ長い華やかな歓楽街を通り抜けなければならない。さらに、それぞれの観光スポットは距離が離れていることが多いため、いたるところでサービス施設が必要になる。ネバダ州の合法なギャンブルも、この地域の観光産業の一部に含めれば、観光業が地域全体に及ぼす影響はさらに大きくなる。

製材業と牧畜:牧畜と製材業は、その基本材の多くを政府の所有地に頼っている。林野部と土地管理局の所有地は誰でも放牧に利用することができ、「人の住まない内陸部」での製材業は、そのほとんどが林野部の所有地で行われている。牧畜と製材のどちらも、1ヘクタール当たりの生産性は、特に私有地と比べて、相対的に低い。

この明白な非効率さの一因は、土地があまり良質でないことである。乾燥した地域の多くでは、ウシが十分な草を食べるのに、1頭当たり40ヘクタールが必要となる。この地域の大半では、季節による気候変動が激しいため、米国でも数少ない季節ごとの移動放牧が行われている。移動放牧とは、家畜の群れを、冬は低地へ、夏には山の牧場や牧草地へと、季節ごとに移動させる放牧方法である。特にヒツジの牧畜にとっては重要である。スペインとフランスの国境にあるピレネー山脈で羊飼いをしていた多くのバスク人が、家畜の群れを管理する契約労働者としてこの地にやってきた。今日では、このバスク人の子孫たちが、ネバダ州などいくつかの州で人口の大部分を占めている。

鉱業:19世紀末には、モルモン教徒のすぐ後に続いて、金の採掘者がこの地域にやってきて定住した。その数はモルモン教徒に次いで2番目に多かった。ネバダ州でカムストック鉱脈が発見されたことから、バージニアシティが生まれた。この町は、1870年ごろの最盛期には人口2万人の都市に成長したが、その後、良質の鉱石の減少とともに、ほぼ消滅してしまった。

カムストック鉱脈発見直後の数年間に、金・銀鉱採掘がブームとなって、ネバダ州の人口が急増した。ついには1864年、近隣諸州に先駆けて、ネバダ州はアメリカ合衆国への編入が認められた。19世紀末までには鉱物資源の多くが枯渇したため、ネバダ州では広い範囲にわたって人口が減少し、20世紀に入ってかなりの時間が過ぎるまで人口が元の水準に戻ることはなかった。今日、ネバダ州にとっても、西部内陸部のどの地域にとっても、鉱業は経済的にあまり重要ではないが、廃墟となった採鉱所の中には、重要な観光名所となっているものもある。

この地域の経済に貢献している鉱物資源で今日最も重要なのは、アリゾナ州とユタ州に生産が集中している銅である。ソルトレークシティ近郊のビンガム鉱山の広大な露天掘りの採掘場は、人間が掘った世界最大の穴と言われており、これまで800万トンほどの銅を産出してきた。アリゾナ州にある大小多数の銅採鉱所のうち、最も重要なのは同州の東部のモレンチにある。そのほかにもサンマニュエル、グローブ、ビスビーなど、すべてすべてアリゾナ州南部に重要な鉱山がある。

「人の住まない内陸部」で採鉱される銅鉱石のほとんどは等級が低く、金属含有量は5%未満である。そのため、ほとんどの鉱山は、近くに溶解または濃縮施設を持ち、出荷物の重量を大幅に軽減することによって、出荷コストを減らしている。このため、金属精製業は、この地域の主要製造業の1つである。

この地域で銅の次に重要なのは鉛と亜鉛だが、この2つはほかのいくつかの金属とともに、同じ場所から採掘されることが多い。例えば、モンタナ州のビュートヒル鉱山は、長年にわたって銅だけでなく鉛と亜鉛の重要な産地であった。アイダホ州北部のクールダレーヌ地区では金、銀、鉛、亜鉛が産出されており、コロラド州のレッドビル地区では上記4種類の鉱物のほか、鉄鋼製品の製造に使われるモリブデンが生産されている。実際、世界のモリブデン供給量の4分の3ほどがレッドビル地区で産出されている。この地域では、ウランの探査も広く行われており、今日ではユタ州とコロラド州がウランの主要産地となっている。年間の石炭採掘量は、およそ2,500万トンである。

ユタ州、コロラド州、ワイオミング州にまたがる数千平方キロメートルの地域に、グリーンリバー地層の広大な油頁岩鉱床が広がっている。この油頁岩の中に1兆バーレルもの石油が眠っている。この量は、全世界の総確定埋蔵量よりもはるかに多い。しかし、操業上、環境上の問題があるため、この開発の大部分は概ね保留になっている。

これらの鉱物資源を基盤として都市が持続的に、または大きく発展したことはほとんどなかった。1990年時点で人口34,000人のモンタナ州ビュートが、この地域で鉱業(銅)を主要経済基盤として発展した最大の町だろう。しかし、ビュートは、農産物加工の中心地としてもまた、長年重要な役割を果たしてきたのである。

*上記の日本語文書は参考のための仮翻訳で、正文は英文です。

The Empty Interior

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, An Outline of American Geography.)

The Empty Interior

By Stephen S. Birdsall and John Florin

Stretching from the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains westward to the Sierra Nevada of California, to the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest and into Alaska, is the largest area of sparse population in America. Its low average population density is the key identifying feature of this region. Indeed, there is much variation in other elements of the territory's geography. Portions have rugged terrain interspersed with a series of plateaus, many of which contain extensive flat areas. Annual precipitation ranges from more than 125 centimeters in northern Idaho to less than 25 centimeters in the plateau country. The population of the region is mostly of European origin, although Hispanic-Americans and American Indians are found in significant proportions in the south. Irrigated agriculture is important in some areas, as is ranching, whereas in other areas, lumbering, tourism, and mining are dominant.

This massive expanse of land contains some of America's most strikingly scenic portions. The impact of humans on the region, although locally important, has been overshadowed to a great degree by the varied splendors of the natural environment.

A DIFFICULT ENVIRONMENT

Eastern Americans are accustomed to an undulating terrain where variations in elevation are seldom dramatic. Where mountains occur, most do not contain an elevation change from the mountain's base to its top that exceeds 1,000 meters. By comparison, dramatic changes of 1,000 meters or more are common in the interior West.

A second element of the region's physical geography is its ruggedness. Most of the mountains of the eastern United States appear rounded and molded; the ranges of the West present abrupt, almost vertical slopes, and the peaks frequently appear as jagged edges pointing skyward. This difference is due partly to age. Most of the western mountains, although by no means all of them, are substantially younger than the eastern ranges. Thus erosion, which results in an eventual smoothing of the land surface, has been active for a much shorter time.

During the most recent period of geologic history, the Pleistocene, the carving done by mountain glaciers did much to form the topography of the interior West, and remnants of the glaciers can still be found in parts of the region. Most widespread in the Pacific mountains of southern Alaska, smaller glaciers are found as far south as the central Rocky Mountains in Colorado and the Sierra Nevada of California.

Alpine glaciers form in higher elevations and gradually flow downhill as the volume of ice increases. The moving ice is a powerful agent for erosion. Where this erosion pattern continues for a sufficiently long time, a deep U-shaped valley is created with almost vertical sides and a relatively flat bottom. If two glaciers flow side by side, a narrow ridge line is formed, characterized by jagged small peaks called aretes. Yosemite Valley in the Sierra Nevada, an almost classic glacially carved valley nearly 2 kilometers deep, is perhaps the region's most photographed example of alpine glaciation.

Most of the Empty Interior is occupied by plateaus rather than mountains. Probably the most scenically dramatic portion of this section is the Colorado Plateau along the middle Colorado River in Utah and Arizona. Although there are some large structural changes in relief, most of the area is underlain by gently dipping sedimentary rocks. The major landscape features are a result of erosion by exotic streams (so-called because they carry water, something otherwise unknown – or exotic – into this arid environment) that cross the plateau, most notably the Colorado River and its tributaries. In this environment, streams are easily the predominant erosive influence. Thus, when accompanied by recent substantial geologic uplift over much of the plateau, great downward erosion has resulted, primarily in the immediate vicinity of the streams. The canyonlands that have been produced are some of the best known examples of America's natural scenic resources. In fact, the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in Arizona is one of the country's most widely recognized natural scenic attractions. In Grand Canyon National Park, a canyon system has been created that is at places more than 16 kilometers wide. In addition, the variable resistance of strong and weak rocks in these sedimentary formations has created an angular pattern of scarps and benches that is especially characteristic of the area.

Filling the country from the Colorado Plateau to the south across southern New Mexico and Arizona, west into Death Valley and the Mojave Desert in California, and as far north as Oregon and Idaho, is the basin and range region. This wide area is composed of a series of more than 200 north-south trending linear mountain ranges that are usually no more than 120 kilometers long and typically rise 1,000 to 1,600 meters from their base within a collection of some 80 broad, flat basins. North and west of the Colorado River basin, most of the area has interior drainage; that is, streams begin and end within the region, with no outlet to the sea. One result is that much of this area has received vast quantities of alluvia eroded from the surrounding mountains.

During the Pleistocene, substantial parts of the region were covered by lakes that resulted from a wetter climate and the melt of alpine glaciers. The largest, Lake Bonneville, covered 25,000 square kilometers in northern Utah. Most of these lakes are gone or greatly diminished in size because stream flow now depends on a lower annual precipitation, and many of the lakes that remain, such as Pyramid Lake in Nevada or Utah's Great Salt Lake, are heavily saline. Flowing water always picks up small quantities of dissolvable salts, which normally make a minor contribution to the salinity of the world's oceans. But because they lack an outlet to the ocean, lakes in the basin and range area have increased their salt concentration. The Great Salt Lake, covering about 5,000 square kilometers, is the remnant of Lake Bonneville and today has a salt content much higher than that of the oceans.

North of the basin and range region, the Columbia Plateau is the result of a gradual buildup of lava flows. Contained by the surrounding mountains, these repeated flows, each averaging 3 to 6 meters thick, have accumulated to a depth of 650 meters in some areas. A few small volcanoes and cinder cones dot the area, but the primary features of volcanic activity here are the vast flows of formerly molten material. Here, too, streams have eroded deep, steep-sided canyons.

With some gaps, the pattern of eroded plateaus continues northward into the Yukon Territory in the area between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Ranges. In central Alaska, the drainage basin of the Yukon River occupies the territory from the Alaska Range to the Brooks Range. Surface materials are mostly sedimentary rocks.

There is a strong association between precipitation and elevation throughout the Interior West. Low-lying areas are generally dry. Heaviest precipitation amounts are usually found on the mid-slopes of mountains. The entire region is almost totally dependent for surface water on the exotic streams.

The association between topography, temperature, and precipitation results in a marked altitudinal zonation of vegetation throughout the Empty Interior. The lowest elevations are generally covered with desert shrub vegetation, most notably sagebrush. In the far south, there is a modest late summer increase in precipitation that allows a sagebrush/grasslands combination. Elsewhere, this combination is found at elevations above the desert shrub. Upslope from the sagebrush is a tree line, above which precipitation is sufficient to support tree growth. The forests are at first a transitional mix of grass and small trees, like pinon pine and juniper. At higher elevations, these blend into more extensive forests of larger trees, such as ponderosa pine, lodgepole pine, and Douglas fir. If the mountains are high enough, smaller trees such as subalpine fir varieties and then a second tree line are encountered. Above this upper tree line, a combination of high winds and a short, cool growing season render tree growth impossible, and the trees are replaced by tundra.

The Empty Interior supports a growing wildlife population that includes the bison (buffalo), the North American elk, the pronghorn antelope, the wild bear, the white-tailed deer, and the wild turkey.

THE HUMAN IMPRINT

In the state of Nevada, various government agencies control almost 90 percent of all land. Although the percentages are lower elsewhere, the basic pattern of governmental predominance is found throughout the Empty Interior.

It is not surprising that so much of the land remains in government hands. This area and Alaska were the final regions to be occupied by any substantial numbers of people, and federal programs of land distribution, designed to encourage agricultural use, were not relevant because little of the region held any real agricultural promise. The U.S. Bureau of the Census proclaimed the end of the settlement frontier in 1890, a time when much of the Interior West still remained unsettled. Also, by the time other interests, such as lumbering or mining, began to push for greater private land ownership, the federal government was reevaluating earlier programs in which it distributed land almost for free.

A substantial part of America's total national park system is found in the interior West, including such famous parks as Yellowstone, Glacier, and Grand Canyon. But the national parks are only a small portion of the total public land area. The largest share of these lands is held by the Bureau of Land Management, a part of the U.S. Department of the Interior, which puts this land to many uses, grazing being the most important. The bureau has also been the main agent in the construction of irrigation and hydroelectric dams in the area.

The Forest Service, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is the second largest of the federal landholders. The service has traditionally emphasized logging and grazing under its multiple-use charge, and it has increased the quality and quantity of recreational uses of the land.

Two other uses of parts of the Empty Interior say much about the region's past and about America's attitude toward the land's quality and usefulness. First, some of the largest American Indian reservations are found here, especially in northern Arizona and New Mexico. Also, some of the country's largest bombing and gunnery ranges, as well as its only atomic bomb testing facility, are found here. The population is sparse, and alternative demands on the land are not great.

As the agricultural frontier moved westward in the late decades of the 19th century, it largely swept past the Interior West. In fact, were it not for minerals, transportation, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, few people would have chosen the region until well into this century.

The Latter-Day Saints, or, more commonly, the Mormons, were established in upstate New York in 1830. The church and its followers were attacked repeatedly, both verbally and physically, for what were considered their "unusual" beliefs. The Mormons moved several times, searching for a place to practice their religion. Many Mormons, often on foot, pushed into the West, where they hoped to create an independent Mormon state.

The locale they selected for their initial western settlement was the Wasatch Valley, tucked between the Wasatch Mountains and the Great Salt Lake in northern Utah, a location that would later become Salt Lake City. It must have seemed an unlikely spot to begin an agricultural settlement. The climate was dry, the lake saline and useless, and the landscape barren. Nevertheless, the Mormons quickly began their agricultural operations; their settlements expanded as new arrivals came. A high birth rate also pushed their population numbers upward. They dreamed of founding an independent country to be called Deseret, stretching northward into what is now Oregon and Idaho and southward to Los Angeles, California, and Mormon communities were established at greater and greater distances from Salt Lake City.

The Mormons ultimately failed in their hopes for creating Deseret. With the discovery of gold in California and Nevada, American expansion moved through and beyond the Mormon area, and the Mormons again found themselves under the will of the United States. Deseret was divided eventually among a half-dozen different states.

The Mormons were the first Americans to face the problems of life in the Interior West, and they solved the majority of them. None of their solutions was more important than irrigation. Americans had previously had no need for extensive irrigation, and the techniques and central control necessary to collect and move water to a large number of agricultural users were almost unknown. The Mormons constructed a large number of storage dams on the western slopes of the Wasatch Range, and many kilometers of canals moved the water to the users in the valley below. The results of these efforts today cover much of the valley with agricultural crops, trees, and green lawns. These early efforts at large-scale irrigation were the beginning of an irrigation boom in the interior West.

Mormons continue to have a substantial impact on the Interior West. Of the roughly 11 million persons found in this region, over 1.5 million are Mormons.

DISPERSED ECONOMIC STRUCTURE

Irrigation and Agriculture: Much of the flow of several of the more important rivers in the Empty Interior is diverted for various uses, with irrigation claiming the largest share. The Reclamation Act of 1902 provided for federal support for the construction of dams, canals, and, eventually, hydroelectric systems for the 17 western states (excluding Alaska and Hawaii). Today, over 80 percent of the water from these federally supported projects is used to irrigate over 4 million hectares. While most of this irrigated land is in California, large irrigation projects are nevertheless scattered throughout the region.

The 1 million hectares irrigated in the Snake River Plain makes Idaho the region's leader in terms of the amount of land irrigated. This enables the state to be among America's leaders in potato and sugar beet production; alfalfa and cattle are also important. The Columbia Valley Reclamation project, supplied by the bountiful waters of the Columbia River impounded behind Grand Coulee Dam in central Washington, contains well over 400,000 hectares, producing such crops as alfalfa, sugar beets, and potatoes. Irrigation along the Wasatch Valley has expanded little since the first decades of Mormon settlement. About 400,000 irrigated hectares there are devoted primarily to sugar beets and alfalfa. The Grand Valley, along the Colorado River in west-central Colorado, produces alfalfa and potatoes as principal crops, although tree fruit, especially peaches, are also important. In Washington, tributaries of the Columbia River, notably the Yakima and Wenatchee, supply water for America's most famous apple-producing regions.

Each of these areas produces a limited set of crops. The region's short growing season precludes production of most long-season crops. And local demand is limited, minimizing the need for dairying or many fresh vegetables.

The more southerly irrigated districts, although affected by irrigation water shortages, nevertheless have one major advantage over their northern counterparts – a far longer growing season. California's Imperial Valley, with a frost-free period in excess of 300 days, is one of America's premier crop producing areas. Much of America's winter head-lettuce supply comes from here, as do grapes, cotton, and alfalfa for fattening beef. The cattle population of the valley is over 250,000 head. A newly constructed electric power generating facility there uses locally abundant cattle manure for fuel. The Imperial Valley's growing season is long enough to support double-cropping, and of course this increases overall productivity.

The Coachella Valley north of the state's Salton Sea produces such crops as dates, grapes, and grapefruit. The Yuma Valley along the lower Colorado River supplies cotton, sugar beets, and oranges. In the Salt River Valley, near Phoenix, Arizona, winter lettuce, oranges, and cotton are the major crops. These southern crops, unlike those grown farther north, face little direct competition from the agricultural centers in the major market areas of the eastern United States.

Transportation Services: Because little traffic is generated within the Interior West, a prime goal of transport developers has been to permit movement across the region as speedily and inexpensively as possible. Consequently, most major highway and rail routes pass through the region east-west, from the urban centers of the Midwest to those of the West Coast.

Despite these requirements of transport design, the great width of the region demands development of many service facilities for the traffic passing through. Many of the towns of the region began as centers established to service and administer the railroads. The centers were founded wherever railroad personnel were needed, whether the region was populated or not. Although fewer local railroad workers were needed as technological innovations were implemented beginning in the late 1940s, this population reduction was more than compensated for by the growing need for people to serve truck and automobile traffic with gas stations, car repair facilities, motels, and restaurants.

Although transport services represented the principal early influence on the growth of urban centers, cities that have become the largest have usually been aided by some additional attribute. Spokane, Washington, with a population of over 350,000, has, for example, become the principal center for the "Inland Empire" of Washington. That area, geographically defined and half encircled by the sweep of the Columbia River across central Washington State, has long had substantial agricultural production. Albuquerque, New Mexico, with a population of about 500,000, has gained a role similar to Spokane's through its centrality and accessibility in that state. Phoenix, Arizona, grew initially as an agricultural center and then boomed as Americans flocked to its warm, dry environment. It has become a retirement center as well as a focus of manufacturing activities, with industries that produce small, high-value products, such as the electronics industry, being particularly important in the city's growth.

Ogden, Utah, is one community that exists as a major rail center and was early among the most important such places in the region, but it has not become a major urban place. It is only about 55 kilometers north of Salt Lake City, a city whose continued dominance derived from its key functions as the capital of Utah and of Mormonism.

Tourism: The variety and appeal of the Empty Interior's scenic wonders attract millions annually. Visitors to most of the major parks must first pass a long, garish strip of motels, snack bars, gift shops, and other sources of local color. In addition, distances between attractions are usually great, and services are thus needed in countless locations. When legal gambling operations in the state of Nevada are included as part of the area's tourist industry, the overall regional impact of tourism becomes even greater.

Lumbering and Ranching: Ranching and lumbering depend on governmental land for many of their basic materials. The holdings of the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management are open to grazing, and most lumbering in the Empty Interior is carried out on Forest Service lands. Levels of production per hectare for both ranching and lumbering products are relatively low, especially when compared with land held in private hands.

One reason for this apparent inefficiency is the limited quality of the land. In many drier areas, 40 hectares of land per head is needed for satisfactory cattle grazing. The great seasonal climatic variations found in much of the region make this one of the few areas in America where transhumance is practiced – a seasonal movement of animal flocks, by those who tend them, from the lowlands in winter to mountain pastures and meadows in summer. It is especially important in the sheep-ranching economy. Many Basques, expert shepherds from the Pyrenees of Spain and France, came to this area as contract laborers to manage the herds. Today, descendants of the Basques are a substantial part of the population of several states, especially Nevada.

Mining: In the late 19th century, gold miners followed shortly on the heels of the Mormons to become the second largest group of settlers in the region. The discovery of the Comstock Lode in Nevada gave rise to Virginia City, which grew into a city of 20,000 during its heyday around 1870 before nearly disappearing with the decline of high-quality ore.

The boom in gold and silver mining in the years immediately following the Comstock discovery created rapid population growth in Nevada. This culminated in the admission of the state into the union in 1864, long before most of its neighbors. The depletion of much of this mineral resource by the late 19th century resulted in a widespread population decline in Nevada, one from which it did not fully recover until well into the 20th century. Today, the mining economy is of little significance to the state--or to any part of the interior West--although some of the abandoned mining centers are important tourist attractions.

Leading today's list of mineral contributions to the region's economy is copper, with production concentrated in Arizona and Utah. The vast open pit of the Bingham mine outside Salt Lake City, said to be the largest human-made excavation in the world, has yielded some 8 million tons of copper. Among the several score major and minor copper-mining centers in Arizona, the most important is at Morenci in the eastern part of the state. Other important mines are at San Manuel, Globe, and Bisbee, all in southern Arizona.

Most of the copper ore mined in the Empty Interior is low grade, with a metal content of under 5 percent. Consequently, most mines have a smelting or concentrating facility located nearby to lessen shipment costs by greatly reducing the weight of the material being shipped. Refining is thus a major manufacturing industry in the region.

Lead and zinc follow copper in regional importance, with the two often joined by several other metals mined at the same location. The Butte Hill mine in Montana, for example, long was a significant producer of lead and zinc as well as copper. The Coeur d'Alene district in northern Idaho produces gold, silver, lead, and zinc; the Leadville district in Colorado has those four plus molybdenum, used in the manufacture of steel products. In fact, some three-quarters of the world's supply of molybdenum comes from the Leadville district. Uranium exploration has also been widespread in the region, and today Utah and Colorado are the principal producing states. Approximately 25 million tons of coal is mined annually.

Spread across thousands of square kilometers of the area where Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming meet are the vast oil shale deposits of the Green River Formation. Locked in these rocks are as much as a trillion barrels of oil, vastly more than the entire proven alternative oil reserves of the world. However, operational and environmental problems have put development of this industry largely on hold.

There has been little sustained or substantial urban growth based on these mineral resources. Butte, Montana, with a population of 34,000 in 1990, is perhaps the region's largest city developed with mining (copper) as the main base of the economy, yet it has long been an important processing center for agricultural products as well.

[Stephen S. Birdsall is dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Michigan State University and is the co-author of four books and atlases, including Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada.]

[John Florin is chair of the geography department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Pennsylvania State University. His recent publications include Atlas of American Agriculture: The American Cornucopia with Richard Pillsbury and Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada with Stephen S. Birdsall.]