国務省出版物

米国の地理の概要 – アパラチアとオザーク山地

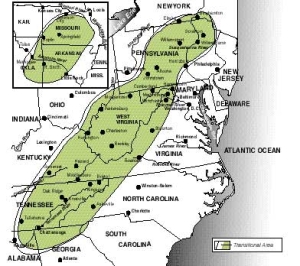

ニューヨーク州からアラバマ州まで広がるアパラチア山地と、オザーク・ウォシタ山地との間は、400キロメートルほど離れている。しかし実際には、この2つの山岳地域は1つの自然地理学的地域に属しており、地勢学的に強い類似性を持っている。また、地勢と人間の定住の間には、ほかに類を見ないほど密接な関連性がある。

初期の開拓者たちは、植民地時代の米国に上陸すると、西方に高い山々が広がっているという噂を耳にした。実際に山に入ってみると、その高さが誇張して伝えられていたことがわかった。アパラチアにしろオザークにしろ、米国西部でよく見られるような、ドラマチックな眺望が得られるのは、ごくわずかな場所だけである。

しかし、地理に詳しい人々のほとんどは、アパラチアとオザークの地形を山岳性と呼ぶことに賛同するだろう。土地によっては高低差が500メートル以上の場所が多く、時には1,000メートル以上に及ぶところもある。傾斜が急な場所も多い。

しかし、地理に詳しい人々のほとんどは、アパラチアとオザークの地形を山岳性と呼ぶことに賛同するだろう。土地によっては高低差が500メートル以上の場所が多く、時には1,000メートル以上に及ぶところもある。傾斜が急な場所も多い。

アパラチア地域の人文地理学的特徴は、今でもその地勢と密接に絡み合っている。ここに山がなければ、この地域は「深南部」のように、単に隣接するいくつかの地域の一部でしかなかったはずである。山があればこそ、「アパラチアとオザーク山地(Appalachia and the Ozarks)」は、ほかの地域とは違う特徴を持った、いかにも米国らしい1地域として存在しているのである。

アパラチア地域は、少なくとも3つの自然地理学的地域で構成されている。この3つに分けた小地域は、概して北東から南西へと、帯状に並んでいる。

最も東に位置する「帯」がブルーリッジ山脈である。「先カンブリア代」の古い岩でできたこの地域は激しく侵食され、現在の最高標高は、影も形もないほど低くなっている。大西洋沿岸の南部低地のうち、ピードモント台地は、ニューヨーク州からアラバマ州まで続くアパラチア山脈の東側で、ブルーリッジ山脈と境界を接している。

ブルーリッジ山脈は、全体として北から南に向かって、高さと幅が増している。南の部分、特にバージニア州ロアノークの南側に、アパラチア地域で最も山が険しい場所がある。ピードモント高原からブルーリッジ山脈にかけては、標高が急激に大きく変化する。ペンシルベニア州とバージニア州では、ブルーリッジ山脈が、ピードモント高原と西のグレートバレーの間を貫く、細長い尾根になっている。この尾根はノースカロライナ州とテネシー州の州境に沿って広がり、最も広い場所では幅150キロメートルにも及ぶ。

ブルーリッジ山脈の西には、尾根と渓谷の地域がある。ここは、ブルーリッジ山脈とロッキー山脈の間にある広大な堆積岩盤の一部である。この岩盤の東端は激しく褶曲して断層を形成し、それが直線的に連なっている。

尾根と渓谷の地域の幅は、平均およそ80キロメートルである。谷を隔てて高さ100メートルから200メートルの多数の尾根が、そびえている。尾根には比較的切れ目が少なく、その大半はこの地域の景観を横切って流れる川によって作られたものである。幅が数キロメートルにも及ぶ渓谷は、アパラチア地域で最も肥沃な農地を提供している。この地域全体の尾根は比較的侵食に強い頁岩や砂岩でできていることが多く、通常、渓谷の地面は石灰岩でできている。

これらの尾根のうち最も東側にある尾根とブルーリッジ山脈の間に、グレートバレーがある。このアパラチア地域のほぼ全体を縦方向に走るグレートバレー(ほとんどのところで、平坦というよりは小高くなっている)は、歴史的に見て、米国の重要な交通路の1つであり、山脈そのものを除けば、地形的特徴の中で何よりもアパラチア地域の人々を最も強く結びつけてきた要素である。

アパラチア地域の最も西側にあるのがアパラチア高原である。その東側はアレゲーニー・フロントと呼ばれる険しい急斜面に接しているが、ここはロッキー山脈より東にある場所としては、西への移動を妨げる、最も大きな難所だった。この地域の地形は、その大部分が、内陸低地の水平な地層が川の流れで侵食してできたものである。侵食によって、険しく切り立った尾根と狭い渓谷が隣接する、起伏の激しい、複雑な地形が生まれた。ニューヨーク州とペンシルベニア州に位置するアレゲーニー台地の北の部分には、南側より丸みのある、穏やかな景観が広がっている。一部を除き、平らな土地はほとんどない。多くのコミュニティは、峡谷の限られた平地に押し込められている。

オザーク山地からウォシタ山脈に至る高地の地形は、アパラチア山脈とほぼ同様の地勢学的区分に属するが、全体として北東から南西ではなく、東西に流れている。ウォシタ山脈の南には、褶曲した尾根と渓谷が平行して連なっている。アーカンソー川流域の樋(とい)のような構造が、谷間がウォシタ山脈とオザーク山地を分けている。オザーク山地は、高原が侵食されてできた、凹凸の激しい丘陵地帯で、アパラチアの台地部分とよく似ている。

開拓者がブルーリッジを越えてアパラチア高地まで入ってきたのは、移民が東海岸に最初に住み着いてから150年後の、植民地時代の終わりごろだった。グレートバレーとその向こうにある山岳地域への経路として、もっとも容易で、最初に使われたルートは、ブルーリッジの高さが丘陵地帯とほとんど変わらない、ペンシルベニア州南東部にあった。多くのペンシルベニア住民たちは、北と西に広がる山地は住むのに適さない土地であると考えた。この結果彼らは、徐々に渓谷を下ってバージニア州に定住するようになった。そしてさらに、南部の低地から内陸に移動する人々がそこに加わった。

その後、18世紀も終わるころになって、人々は周辺の高地にある渓谷や谷間に住むようになった。彼等が選んだ土地は、さらに遠くの西方にある地域と比べて痩せていた。起伏が激しく、寒冷な高地気候だったため、この地域のほとんどは農園経営に適していなかった。一握りの大規模農園が発達したのは、もっと広い一部の低地だけだった。

18世紀末から19世紀初頭にかけて開拓者がこの土地に来たとき、この地域は小規模農業に適している可能性も十分あった。農民1人が管理できる開拓地は、面積にして約10-20ヘクタールにすぎず、このような狭い土地であれば、渓谷にも存在した。森林は猟獣の獲物であふれ、木材も豊富だった。そして、森や山の牧草地で家畜を放牧することもできた。当時の基準では、これはなかなかの土地と言えたため、すぐに農民が山に定住するようになった。

この地域の大半は、次第に他の地域から隔絶し、孤立していった。より平坦で肥沃な土地が西部で開拓され、穀物生産が機械化されるにつれ、小規模なアパラチア農場の経済的重要性は次第に低下していった。バージニア州の西端に位置するカンバーランド・ギャップや、そこからケンタッキー州のブルーグラス盆地に至る「ウィルダネス・ロード(Wilderness Road)」などのような、この地域を走る有名な交通路でさえも、実際には曲がりくねった、進むのが困難な道だった。

北東部海岸線と五大湖地方の東西間の移動には、アパラチア高地北部を避け、モホーク・コリドーを通る平坦なオンタリオ湖畔の道が使われた。アパラチア高地南部には、簡単に進める経路が全くなかった。主要な鉄道路線は、この地域を迂回して作られていた。

アパラチア地方、特にその南部では、大都市の発展が遅れていた。ひとつには、この地域が南部のほかの地域と同様、農業に力を入れていたからである。他の地域で製造業や都市生活への転換が猛烈な勢いで進み始めた後も、この農業一辺倒の状況はしばらく続いた。また、アパラチア地域の産物は種類が少なく、都市の製品やサービスに対する需要も限られていた。これに加えて、輸送手段にも乏しかったのである。

大規模農場が生まれず、都市開発も進まなかったことの重大な結果として、初期の開拓者以降、新しい移住者がこの地域に入植してくることはほとんどなかった。初期の開拓者たちは今いる場所に住み続ける傾向があり、時間の経過とともに家族、地域共同体、土地に対する愛着が増していった。このように地域住民の移動が少なかったことから、米国のほかの地域では見られないような、独自の文化的特徴が発達した。アパラチアは単に昔のままでいることによって、ますます独自性を高めていった。

アパラチア地方の住民は比較的貧しい。地域によっては、1940年代に採炭が機械化され、地域の労働需要が大幅に減少したことが、貧困の主な原因と見ることもできる。これは特に、アパラチア地方の主要石炭産出地域であるケンタッキー州東部にあてはまる。

アパラチア住民の生活態度は保守的である。米国で最も保守的なプロテスタント教会の多くは、アパラチア地方に由来を持つ。また、山の住民が移住して自分たちの宗教を持ち込んだ場所を起源とする教会もある。政治的には、この地方選出の公職者のほとんどは決定的に保守的だが、地方ポピュリズムの要素も見受けられる。この地方偏愛主義は、相対的な孤立状態の中で生まれた家族やコミュニティの強い絆により育まれた。この絆によって家族やコミュニティの結束が固くなり、ほかの地域との関係が弱まっている。

この地域の南部は、最もアパラチア的な色彩が濃く、多くの米国人もアパラチアと認めている場所である。しかし、この地域の住民についてここで述べてきた事柄の多くは、オザーク山地や、もっと北のアパラチア地方にも当てはまる。

アパラチア北部とアパラチア全域とのつながりは、南部に比べて不明確である。確かに、山の多い地形を共有しているし、険しい傾斜で初期の開拓が困難だったことも共通している。しかし、南部と比べてさほど貧困ではない。また、初期の北西ヨーロッパ系の開拓者に続いて、比較的新しい移民がこの地域に入植している。特にペンシルベニア州とウェストバージニア州北部では、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて、炭鉱の仕事が多くの東欧系移民をこの地に引き寄せた。

宗教を筆頭に、アパラチア地方北部の文化様式の多くは、南部高地とはまったく違っている。キリスト教原理主義教会はそれほど一般的ではなく、多くの郡、特にペンシルベニア州内では、カトリック教徒と、様々な会派の東方正教会の教徒が過半数を占める。

アパラチア地方北部の輸送網は、南部よりも急速に充実していった。その一因としては、南部と比べて山が連続しておらず、標高も低かったため、切り開くのが容易だったことを挙げることができる。また、中西部の北部が急速に発展すると、アパラチア北部は、北米大陸の主要な商業・製造業発展地帯の中心になった。製造業の中核地域の東西を結ぶ輸送網が山岳地域を貫いて急速に発展した。この結果、アパラチア地方北部、特にペンシルベニア州中部と西部およびニューヨーク州では、アパラチア南部と比べて経済が著しい発展を遂げた。

アパラチア地方に対して米国民が抱くイメージが「田舎」であることは疑いない。これはある程度当たっている。この地域の都市化の比率は、全国平均のおよそ半分でしかない。住民の大多数は、農村人口、または農村の非農家居住者人口(農村に住むが、都市の職業に従事している人々)に分類されている。しかし、アパラチア地方の高い農村の人口密度は、大規模な商業的農業システムによって支えられているわけではない。むしろ、農村人口密度の高さは小規模農業や鉱物資源(主に石炭)に依存している。

アパラチアは米国で自作農が最も盛んな地域であり、ケンタッキー州とウェストバージニア州が、この分野でこの国をリードしている。アパラチア地方には重要な商品作物がないため、初期に小作制度が発展することはほとんどなく、その傾向は今も残っている。

アパラチア地方の平均的な農場の広さは約40ヘクタールしかない。さらに、この地域の大部分は地形が険しく、土壌もやせており、耕作期間も短い。このため、農作物栽培に適した土地が限定される結果となり、相対的に放牧や牧畜に力を入れるようになった。畑が狭く、渓谷に散らばっているため、大規模農業機械を効率的に使うことはほぼ不可能である。これら諸々の要因がすべて重なった結果、農業収入は低い。地域の農民の大多数は副収入を得るためにパートタイムの仕事につき、やっと農業を続けている。

この地域のほとんどで見られる農業は、一般農業と呼ばれる。つまり、特定の生産物ないしその組み合わせが、農家の収入の大部分を占めることがない、という形態だ。険しい斜面の農業利用に最も一般的で、恐らく最も適しているのは、粗放的な畜産業である。渓谷地域では、タバコ、リンゴ、トマト、キャベツなど多数の作物が、地域的重要性を持っている場所もある。狭い畑で栽培するタバコが、アパラチア南部では最も一般的な換金作物である。トウモロコシはこの地方で最も重要な条播作物だが、通常は家畜の飼料として使われる。

このように、この地域の農業パターンは収支ぎりぎりといったところだが、いくつかの重大な例外がある。例えば、バージニア州のシェナンドア川流域は、かつてバージニアの穀倉地帯と呼ばれていたが、深南部とグレートプレーンズの肥沃な草原地帯で栽培される小麦との競争によって、19世紀末に、小麦の市場から締め出されてしまった。今でも秋蒔き小麦は栽培しているものの、飼料用の干草とトウモロコシ、そしてリンゴがこの地域の主要作物となっている。七面鳥の飼育も地元では重要である。ペンシルベニア州中部の多くの渓谷では、酪農とリンゴの生産が重要である。テネシー川流域も立派な農業地帯であり、飼料用作物と畜産が最も重要である。

アパラチア地方の大部分で、農業の強力な相棒とも言える産業は、石炭である。アレゲーニー台地のほぼ全域で、地下には一連の瀝青炭層が広がっており、全体として世界最大の瀝青炭鉱地区を形成している。侵食活動によってアレゲーニー台地の起伏に富んだ地形を作り出したものと同じ水流の働きで、石炭層は露呈している。

アパラチアの石炭は、1860年代の南北戦争直後に重要性が高まった。コークスを燃焼させる新たなタイプの鉄鋼炉の開発によって、こうした新たな需要が生み出された。というのも、コークスは瀝青炭を加工して作られるからである。この時代に、ペンシルベニア州南西部とウェストバージニア州北部の厚い石炭層から燃料を得て、ペンシルベニア州ピッツバーグは「鉄鋼の町」としての地位を確立した。20世紀になってエネルギー源として電力が使われるようになると、アパラチアの石炭は、東海岸沿いや内陸の製造業の中心にある発電所に、燃料を供給した。

ほぼ1世紀にわたって成長を遂げた後、石炭産業は1950年代から斜陽の時代を迎えた。石油と天然ガスが石炭に替わる主な燃料源になると、石炭の生産量は落ち込んだ。1950年から1960年にかけて、石炭を主要産業とする多くの郡は、人口の4分の1を完全に失った。その結果もたらされた経済不況と、アパラチア地方に特有の貧困とが重なって、ここは特に難しい問題を抱える地域となった。

今日では、電力需要の増加に加え、石油の埋蔵量と採掘コスト、原子力の安全性に関する絶え間ない懸念から、発電における石炭の必要性が再認識されている。新しい発電所では、地元産の石炭を大量に使って発電しており、その大部分は地域外にも送電される。毎年1億トン近くのアパラチア石炭が輸出されている。

アパラチア石炭の採掘にはいくつかの方法がある。最初に使われたのは、坑内採鉱または縦坑(立坑)式採鉱と呼ばれる方法であり、特にこの地方の北部では今でも重要な採鉱方式である。現代の坑内採鉱技術(巨大な可動式ドリルと連結した採炭機械を使って石炭を石炭層からはがし、ベルトコンベアの上に乗せて地上まで運ぶ)を使えば、毎分数トンの石炭を石炭層から採ることができる。

露天採鉱は、石炭層が地表近くにある場合には、かなりコストを抑えられる方法であり、重要度が著しく高まっている。今日最も重要な石炭の産地であるこの地方の中央部(主にケンタッキー州東部、バージニア州西部、ウェストバージニア州南部)では、大型機械を使って石炭層の上の斜面から岩を取り除き、露呈してきた石炭を垂直に持ち上げるだけである。斜面に沿っていくつかの石炭層をこの方法で採掘すると、独特な階段状の形状ができあがり、遠くからは、上に行くほど小さくなる箱が、いくつも重なり合っているように見える。

ケンタッキー州で採掘される石炭のおよそ半分と、オハイオ州とアラバマ州産の石炭のほとんどは露天鉱から採掘され、またペンシルベニア州、バージニア州、ウェストバージニア州産の石炭のほとんど、そしてアパラチア地方全体で採掘される石炭の3分の2には、縦坑式採掘法が使われている。

アパラチア地方で最初の重要な炭田は、台地にある瀝青炭田ではなかった。その前に、ペンシルベニア州内の尾根と渓谷の地域の北端にある、無煙炭の開発が行われた。無煙炭は硬くて、煙の出ない、暖房用の石炭である。1860年代に瀝青炭からコークスを作る技術が開発されるまでは、鉱石の溶解に使う主要燃料でもあった。暖房用石炭の使用量が減少したことに加え、無煙炭の代替用途がなかったことから、無煙炭生産地は経済不況に陥った。無煙炭の埋蔵量は依然、豊富だが、今日の産出量はごくわずかである。

石炭はアパラチアの人々にとってありがたくもあり、また迷惑の種でもあった。石炭はこの地域の大部分にとっては、長い間経済的な大黒柱であり、直接または間接的に何十万人もの労働者を雇用してきた。しかし一方で、何万という人が採掘関連の事故で犠牲となった。また、長年炭塵を吸いつづけてきた結果、炭塵肺症に苦しむ人が無数にいる。近年、市場の需要増に対応して産出量が回復しているが、これは機械化が大幅に進んだことが主な要因である。ほとんどの採掘権は、これを早い時期に低価格で取得した企業が保有している。アパラチア地方の多くの州は、自州で採掘された石炭に課税したり、税率を引き上げたりしているが、石炭税は今も低率で、石炭収益のほとんどは外に出て行ってしまう。

その他の採鉱事業として、オクラホマ、カンザス、ミズーリの州境が接するオザーク山地の「トライステート(3州)」地域が、古くから鉛採掘の主要地域だった。アパラチア地方の外に位置するミズーリ州南東部では、250年以上にわたって鉛が産出しており、その露天鉱床は今でも米国で最も重要である。米国でこれまでに採掘された鉛のほとんどはミズーリ産である。同州は現在、全米の総産出量の4分の3以上を占めている。

米国で最初の油井が掘られたのは、1859年、ペンシルベニア州北部でのことで、その後ほぼ19世紀を通じて、石油生産で米国をリードしていた。今日、この地域が供給する原油だけでは、国の需要のごく一部しか満たすことができないが、依然として高品質の石油や潤滑油の重要な産地の1つである。

最後に、テネシー州南東部は、米国内に残っている最も重要な亜鉛生産地である。さらに、ノースカロライナ州とジョージア州の州境に近いテネシー州ダックタウンの周辺にはいくつか銅山があり、ミシシッピ川東岸で唯一の主要銅産地となっている。

石炭と同様、アパラチアの河川も、この地域にとってはありがた迷惑な代物だった。確かに、重要な輸送ルートとなった川もいくつかあるし、最も初期の時代の製粉所や製材所は、水力を利用していた。しかし、これらの河川には負の側面もあった。豪雨になると、狭い渓谷を頻繁に洪水が襲ったからである。南部の山岳地方は、西の太平洋沿岸を除けば米国内で最も雨の多い地域である。

これらの河川の1つであるテネシー川を安全管理したいという願いから、米国史上最大で、おそらく最も成功を収めた地域開発計画が実施された。1930年代に、テネシー川を利用してその流域全域の経済状況を改善するための計画が立案された。そして、このテネシー川流域開発公社(TVA)に最初に与えられたのは、テネシー川を開発して航行に適した川にする任務だった。今日では、喫水3メートルのはしけ(艀船)が航行できる水路が、はるか上流のテネシー州ノックスビルまで続いている。

このほかのTVAの活動は、そのほとんどが、最初の任務の論理的延長線上にあると見ることができる。水路の開発には、流量を確保し、洪水を減らすための一連のダムの建設または購入が含まれていた。ダムがある以上、水力発電所も併設するのが当然だった。今日では、TVAがテネシー川とケンタッキー川で管理する30以上のダムのほとんどに、発電施設が備わっている。とは言うものの、TVA施設で作られる電力の約80%は、石炭を燃料とする10基を含む火力発電所と、数カ所の原子力発電所で発電される。TVAは年間5,000万トン近くの石炭を使っており、アパラチア地方最大の石炭使用者である。

安価な電力に引き寄せられて、ノックスビルの南の大規模アルミ加工施設など、電力を大量に使用するいくつかの産業が、テネシー川流域に集まってきた。米国で最初の原子力研究施設は、ノックスビルの西にあるオークリッジに置かれたが、その理由のひとつは、大量の電力が入手できたことにあった。ノックスビルやチャタヌーガ、ブリストル・ジョンソンシティ・キングスポートの「トライ・シティーズ(3都市圏)」は、すべて重要な製造業の中心地である。TVAはまた、もう1つの電力大量消費型産業である化学肥料の主要な開発・生産者にもなった。

TVAは、ダムの上流域の農民を支援して、川による農地の侵食を抑制する重要なプログラムに着手した。その目的は洪水の原因となる水の一部を農地で吸収させ、湖がシルト(土砂)で埋まるのを遅らせることにあった。

TVAは、川そのものだけでなく、その沿岸の一部にある52万ヘクタールの土地も所有していた。この土地の中に大型の公共のレクリエーション地域が開発され、現在では立派なレクリエーション施設となっている。

連邦議会は1965年に、アパラチア再開発法を可決し、アパラチア地域委員会(ARC)が設立された。同委員会はニューヨーク州からアラバマ州までの地域を管轄し、これまでに同地域の経済改善計画に数十億ドルを投じている。アパラチア地方の高速道路網を発展させることを主眼としたもので、それによって、この地域の孤立した状況を緩和し、製造業をこの地域に誘致することを期待している。

もう1つの政府の活動であるアーカンソー川航行システムは、1960年代から70年代にかけて建設され、1971年に開通した。アーカンソー川とミシシッピ川の合流地点から、タルサのわずか下流にあるオクラホマ州カトゥーサまで、喫水3メートルの船が航行できる運河が作られたのである。その結果、はしけの輸送量と同時に、アーカンソー川の水量を安定させるために建設された多くのダムによる水力発電量も増加した。

この地域の未来はどうなるのだろうか。「アパラチアとオザーク山地」が「米国製造業の中核地域」になりそうもないのは確かであり、ここにはそれを望んでいる人もほとんどいない。それでも、変化の兆しは見える。ジョージア州、南北両カロライナ州、テネシー州の南部高地地方の一部では、レクリエーションを目的とした別荘の建設がブームになっている。ノースカロライナ州、バージニア州、そしてオザーク山地やウォシタ山脈には、富裕階級の逃避地がある。長期的に見れば、この地域から外への移住者は、まったくなくなることはないものの、減少傾向にある。また、この地域の住民1人当たりの所得と全米平均との格差も縮小してきている。経済的に最悪の時期は、おそらく脱したと言えるだろう。

*上記の日本語文書は参考のための仮翻訳で、正文は英文です。

Appalachia and the Ozarks

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, An Outline of American Geography.)

Appalachia and the Ozarks

By Stephen S. Birdsall and John Florin

The Appalachian Uplands, stretching from New York to Alabama, and the area of the Ozark-Ouachita mountains are separated by some 400 kilometers of land. They are actually two parts of a single physiographic province that have a strong topographic similarity and an unusually close association between topography and human settlement.

Early settlers, when they reached the shores of colonial America, heard tales of a vast range of high mountains to the west. As they moved into those mountains, they discovered that their elevation had been exaggerated. Only in a few small areas do the Appalachians or Ozarks approach the dramatic vistas so common in the West.

Nevertheless, most who concern themselves with such questions would agree that much of the Appalachian and Ozark topography should be called mountainous. Local relief is greater than 500 meters in many areas, and it is sometimes greater than 1,000 meters. Slopes are often steep.

The human geography of Appalachia remains closely intertwined with its topography. Without the mountains, the area would merely be a part of several adjoining areas, such as the Deep South. With them, Appalachia and the Ozarks exist as a distinctive and identifiable American region.

A VARIED TOPOGRAPHY

Appalachia is composed of at least three physiographic provinces. These sub-areas are arranged in parallel belts lying roughly northeast-southwest.

The easternmost belt is the Blue Ridge. Composed of ancient Precambrian rocks, this section has been severely eroded, and its highest elevations are currently only a fraction of their former levels. The Piedmont section of the Atlantic southern lowlands bounds the Blue Ridge along Appalachia's eastern side from New York to Alabama.

The Blue Ridge generally increases in elevation and width from north to south. In the south, especially south of Roanoke, Virginia, is the most mountainous part of Appalachia. The changes in elevation from the Piedmont onto the Blue Ridge are usually abrupt and substantial. In Pennsylvania and Virginia, the Blue Ridge is a thin ridge between the Piedmont and the Great Valley to the west; along the North Carolina-Tennessee border, it broadens to a width of nearly 150 kilometers.

To the west of the Blue Ridge, one encounters the ridge and valley section. This is part of the great expanse of sedimentary rock beds that lie between the Blue Ridge and the Rocky Mountains. The eastern edge of these beds has been severely folded and faulted, resulting in a linear topography.

The ridge and valley section averages about 80 kilometers in width. It is occupied by many ridges, usually rising 100 to 200 meters above the separating valleys. Gaps in the ridges are relatively infrequent and usually have been created by rivers that cut across the grain of the area. Several kilometers wide, the valleys provide some of the best farmland in Appalachia. The ridges throughout this section generally are composed of relatively resistant shale and sandstone, and the valleys usually are floored by limestone.

Between the Blue Ridge and the first of the ridges is the Great Valley. Running virtually the entire length of the region, the valley (which is hilly rather than flat in most areas) is historically one of the important routeways in America, and one that has tied the people of Appalachia together more than any other physical feature save the mountains themselves.

The westernmost part of Appalachia is the Appalachian Plateau. The plateau is bounded by a steep scarp (slope) on the east called the Allegheny Front, which was the most significant barrier to western movement in the country east of the Rocky Mountains. The topography of this region has been created largely through stream erosion of the horizontal beds of the interior lowland. Erosion created a rugged, jumbled topography, with narrow stream valleys bordered by steep, sharp ridges. The northern portion of the Allegheny Plateau, in New York and Pennsylvania, has a rounder, gentler appearing landscape. Except for limited areas, level land is scarce. Most communities are forced to squeeze themselves into small level spaces in the stream valleys.

The Ozarks-Ouachita uplands follow a topographic regionalization broadly similar to the Appalachians, with the "grain" now east-west instead of northeast-southwest. The Ouachita Mountains to the south exhibit a series of folded parallel ridges and valleys. They are separated from the Ozarks by the structural trough of the Arkansas River Valley. The Ozarks is an irregular, hilly area of eroded plateaus, much like the Appalachian Plateau section.

THE APPALACHIAN PEOPLE

Settlers did not push through the Blue Ridge into the Appalachian Highlands until late in the colonial period, 150 years after initial occupation of America's East Coast. The easiest and first-used passageway into the Great Valley and the mountains beyond was in southeast Pennsylvania, where the Blue Ridge is little more than a range of hills. Many Pennsylvanians found the mountain lands to the north and west inhospitable. Consequently, they gradually spread their settlement down the valley into Virginia. They were soon joined by others moving inland from the southern lowlands.

Then, late in the 18th century, people began settling the valleys and coves of the surrounding highlands. The land they chose was poor in comparison with areas farther west. Its ruggedness, coupled with the cool upland climate, rendered most of the region unacceptable for the plantation economy. Only in some of the broader lowlands did a few sizable plantations develop.

When American settlers came to this area in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the region provided adequate settlement potential for smaller farms. About 10 to 20 hectares of cleared land was all a farmer could handle. Such plots were available in the stream valleys. The forests teemed with game, wood was plentiful, and animals could graze in the woods and mountain pastures. By the standards of the time, this was reasonably good land, and a farming population soon occupied the mountains.

Much of the region gradually grew more isolated and separate from other areas. As flatter, richer agricultural land to the west was opened and grain production was mechanized, the small Appalachian farm became increasingly marginal economically. Even famous pathways through the region, such as the Cumberland Gap at the western tip of Virginia and the Wilderness Road from there to the Bluegrass Basin of Kentucky, were, in fact, winding and difficult.

East-west travel between the northeastern seaboard and the Great Lakes area followed the route of the Mohawk Corridor and the flat lakeshore of Lake Ontario, thus avoiding the northern Appalachian uplands. There was no easy passage at all across the southern Appalachians. Major railroad lines skirted the area.

Appalachia, particularly southern Appalachia, was slow to develop any substantial urban pattern. In part, it shared with the rest of the South an emphasis on agriculture that continued well after other regions of the country had begun their rush toward manufacturing and urban living. Also, the products of Appalachia were few, and the demand for the goods and services of cities was limited. Added to this was the paucity of transportation.

One major result of the lack of both plantations and urban development was that few new migrants were added to the early settlers. These people tended to stay where they were, and, as time passed, their attachment to family, community, and land grew. This regional immobility led to the development of a cultural distinctiveness uncommon in the rest of the United States. Appalachia became increasingly unusual by simply remaining the same.

Appalachia's people are relatively poor. In some areas, especially eastern Kentucky, Appalachia's major coal-producing area, much of the blame for the area's poverty can be attributed to a great decline in the regional demand for labor as coal mining was mechanized in the 1940s.

The region's people are conservative in attitude. Many of America's most conservative Protestant churches trace their roots to Appalachia. Others are found where mountain people have moved and taken their religion with them. Politically, most elected officials are decidedly conservative, although strands of rural populism are found. The area's provincialism is bred of the strong bonds of family and community formed in relative isolation, which tie their members together and lessen their association with others.

The southern portion of the area is the most clearly Appalachian, and the one that most Americans recognize as Appalachia. But much of what has been said here about the region's residents fits the Ozarks and the Appalachian region to the north as well.

The northern Appalachians are far less clearly associated with the broader region. Certainly they share the mountainous topography, and some of the early developmental problems created by steep slopes were also common. But poverty is far less evident than it is farther south. Also, more recent immigrants followed the early northwestern European settlers into the area. This is especially true in Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia, where coal mining attracted many East European migrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Many cultural patterns in the northern Appalachians, with religion a notable example, are not at all the same as those of the southern highlands. Fundamentalist churches are less common; in many counties, especially in Pennsylvania, Catholics and members of various Eastern Orthodox churches are in the majority.

Transportation within the northern Appalachians soon became far better than that in the southern Appalachians, in part because the mountains were less continuous and lower and, thus, more easily breached. Also, as the upper Midwest boomed, the northern Appalachians became the center of the continent's major belt of commercial and manufacturing growth. Transport lines connecting the eastern and western portions of the manufacturing core region soon ribboned through the mountains. The economic consequence of this was far more development within the northern Appalachian area, especially in central and western Pennsylvania and New York, as compared to the southern Appalachians.

ECONOMIC AND SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

The national image of Appalachia is unquestionably rural. In some ways, this is valid. The urban percentage for the region is only about half the national average. A majority of the population is classified as either rural or rural nonfarm residents (people who live in rural areas but have urban occupations). However, Appalachia's high rural density is not supported by a large-scale, commercial agricultural system. Rather, small farms and minerals dependency (primarily coal) are the keys to this dense population.

Appalachia is America's primary region for owner-operated farms, with Kentucky and West Virginia leading the country in that category. Without any important commercial crop in Appalachia, there was little early growth of farm tenancy, and that pattern has remained.

The average farm in Appalachia contains only about 40 hectares. Furthermore, the rugged topography, poor soil, and short growing season in much of the region have resulted in a limited amount of available cropland and a greater relative emphasis on pasturage and livestock. Because fields are small and scattered in the valleys, the efficient use of large farm machinery is nearly impossible. The net result of all this is that farm incomes are low. A great many of the region's farmers turn to part-time jobs to provide supplementary income that will allow them to remain on the farms.

The type of agriculture found in most of the region is called general farming; that is, no discernible product or combination of products dominates the farm economy. Extensive animal husbandry is the most common and probably best agricultural use of the steep slopes. A number of crops, such as tobacco, apples, tomatoes, and cabbage, are locally important in some valley areas, with small plots of tobacco being the most common cash crop in the southern Appalachians. Corn is the region's leading row crop, but it is normally used on the farm for animal fodder.

There are important exceptions to this pattern of semi-marginal agriculture. The Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, for example, was early called the breadbasket of Virginia. Competition from wheat grown in the fertile grasslands of the Deep South and Great Plains forced the valley out of the national wheat market in the late 19th century. Although winter wheat is still grown, hay and corn for fodder and apples are now the valley's major crops, with turkey-raising also locally important. Dairying and apple production are important in the many valleys of central Pennsylvania. The Tennessee Valley is also a substantial agricultural district, with fodder crops and livestock most important.

Over much of Appalachia, farming's chief partner is coal. Almost all of the Allegheny Plateau is underlain with a vast series of bituminous coal beds that together comprise the world's largest such coal district. The coal seams have been exposed by the same streams that have, through their erosive activity, created the rugged topography of the plateau.

The coal of Appalachia became important shortly after the U.S. Civil War in the 1860s. It was the development of new types of coke-burning iron and steel furnaces that created this demand, because coke is processed from bituminous coal. The thick coal seams of southwestern Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia provided the fuel for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to rise to its status of Steel City during this period. As the nation turned to electrical power in the 20th century, coal from Appalachia provided fuel for electric-generating facilities along much of the East Coast and in the interior manufacturing core.

After the better part of a century of growth, the coal industry fell into a period of decline beginning in the 1950s. Production dropped as petroleum and natural gas replaced coal as major fuel sources. Between 1950 and 1960, many coal counties lost a full one-quarter of their population. The resulting economic depression, blending with the poverty common to Appalachia, created areas of particularly severe problems.

Today, growing power demands, coupled with continuing concern over the availability and cost of petroleum supplies and the safety of nuclear power, have reemphasized the need for coal in electric power generation. New generating plants use huge quantities of locally mined coal to produce electricity, much of which is transmitted to areas outside the region. Nearly 100 million tons of Appalachian coal is exported annually.

Appalachian coal is mined in several different ways. Underground or shaft mining was used first and is still quite important, especially in the northern parts of the region. Modern underground mining techniques – huge mobile drills and continuous mining machines that rip the coal out of the seams and then deposit it on conveyor belts for the trip to the surface – mean that tons of coal per minute can be removed from a seam.

Surface or strip mining, which is far less expensive if the coal seams are near the surface, has increased greatly in importance. In the central region (primarily eastern Kentucky, western Virginia, and southern West Virginia), where the most important producing section is today, large machines remove the rocks along a slope above a coal seam and then simply lift off the uncovered coal. Extraction along several seams on a slope by this method creates a peculiar, stepped appearance that looks from a distance like a series of increasingly smaller boxes piled on top of one another.

About half of the coal mined in Kentucky and most mined in Ohio and Alabama is from strip mine lands, while most of the coal from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia – and two-thirds of that from Appalachia as a whole – is from shaft mines.

The first important coal field in Appalachia was not the bituminous fields of the plateau. Their exploitation was preceded by operations in the anthracite field at the northern tip of the ridge and valley in Pennsylvania. Anthracite is a much harder, smokeless coal that was important in home heating. Anthracite was also a major fuel for ore smelting until techniques to produce coke from bituminous coal were developed in the 1860s. The decline in use of coal for heating, coupled with the lack of alternative uses for anthracite, led to an economic depression in the anthracite belt. Although substantial anthracite reserves remain, production today is minimal.

Coal has been a mixed blessing to the people of Appalachia. It has long been the economic mainstay for large parts of the region and has employed, either directly or indirectly, hundreds of thousands of workers. Still, tens of thousands have died in mine-related accidents. Black lung, the result of many years of breathing too much coal dust, has affected countless others. The recent recovery of production in response to increased market demands has been accomplished mainly by greater mechanization. Most mineral rights are held by corporations that obtained them early and at low prices. While a number of Appalachian states have either initiated or increased surcharges on coal mined in their state, coal taxes remain low, and most coal profits leave the region.

In other mining activities, the Tri-State district in the Ozarks, where the borders of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri meet, has long been a major area of lead mining. Southeastern Missouri, outside Appalachia, has produced lead for over 250 years, and surface mines there remain America's most important. Missouri has supplied most of the lead ever mined in the United States and currently produces more than three-quarters of the total national production.

The first oil well in the United States was drilled in northern Pennsylvania in 1859, and that state led the country in production through most of the 19th century. Today, the area supplies only a small part of the nation's crude oil needs, but it remains an important producer of high-quality oils and lubricants.

Finally, southeastern Tennessee is the most important remaining area of zinc production in the United States. In addition, several mines around Ducktown, Tennessee, near the North Carolina and Georgia borders, are the only major copper producers east of the Mississippi River.

REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS

Like coal, Appalachia's rivers have been a mixed blessing to the region. Some of the streams have been important transportation routeways, and water power was used by the earliest gristmills and sawmills. These rivers also had a darker side, for they frequently flooded their narrow valleys during periods of heavy rain. The southern highlands are the moistest area of the country east of the Pacific coast.

Out of a desire to control one of these rivers, the Tennessee, the largest and perhaps most successful regional development plan in American history was implemented. In the 1930s, a plan was conceived to harness the river and to use it to improve the economic conditions of the entire Tennessee Valley. As a result, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was first given the charge to develop the Tennessee River for navigation. Today, a three-meter barge channel exists as far upstream as Knoxville, Tennessee.

Most of the other activities of the TVA can be viewed as logical extensions of the initial commitment. Navigation development included the construction or purchase of a series of dams to guarantee stream flow and reduce flooding. As long as the dams were there, it was natural to include water-power facilities with them. Today, most of the more than 30 dams controlled by the TVA on the Tennessee and Kentucky Rivers have power-generating facilities. About 80 percent of the electricity produced at TVA facilities comes from thermal plants, including 10 that burn coal, and several nuclear-powered facilities. The TVA uses nearly 50 million tons of coal annually and is Appalachia's largest coal user.

The inexpensive electricity attracted to the valley a few industries that are heavy users of power, including a large aluminum-processing facility south of Knoxville. The country's first atomic research facility was placed at Oak Ridge, west of Knoxville, partly because of the availability of large amounts of power there. Knoxville, Chattanooga, and the Tri-Cities of Bristol, Johnson City, and Kingsport are all substantial manufacturing centers. The TVA also became a principal developer and producer of artificial fertilizers, another heavy power-consuming industry.

Above the dams, the TVA initiated a major program to help valley farmers control erosion at the farm. The goal was to hold part of the floodwaters at the farm and to slow the rate at which the lakes were filling with silt.

In addition to the water itself, the Authority owned 520,000 hectares of land along parts of the rivers. Major public recreation areas were developed on some of this land, and the area is now a substantial recreation facility.

In 1965, Congress passed the Appalachian Redevelopment Act, which created the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). Responsible for an area that extends from New York to Alabama, the commission has spent several billion dollars in a program to improve the region's economy. Its primary thrust is to improve highways in Appalachia in the hope that this will decrease isolation and encourage manufacturers to locate in the region.

An additional government activity, the Arkansas River Navigation System constructed during the 1960s and 1970s and dedicated in 1971, established a three-meter navigation canal up the Arkansas River from its confluence with the Mississippi River to Catoosa, Oklahoma, just downstream from Tulsa. The result has been an increase in barge traffic and the production of hydroelectric power from the many dams constructed to stabilize the river's flow.

What of the region's future? Certainly Appalachia and the Ozarks are not likely to become part of America's Manufacturing Core, and few in these regions really want that. Still, there is a sense of change. Parts of the southern highlands in Georgia, the Carolinas, and Tennessee have witnessed a boom in recreational and second-home construction. Havens for the well-to-do are found in North Carolina, Virginia, and the Ozarks and Ouachita Mountains. The long-term pattern of out-migration from the region, while not ended entirely, has been reduced, and the gap between per capita income levels in the regions and the United States has narrowed. Economically, perhaps the worst is over.

[Stephen S. Birdsall is dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Michigan State University and is the co-author of four books and atlases, including Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada.]

[John Florin is chair of the geography department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Pennsylvania State University. His recent publications include Atlas of American Agriculture: The American Cornucopia with Richard Pillsbury and Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada with Stephen S. Birdsall.]