国務省出版物

米国の地理の概要 – 迂回された東部

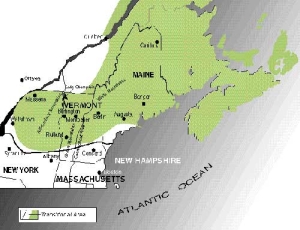

米国東部の地図を見ると、ボストンから北の大西洋沿岸には大都市が存在していないことがよくわかる。ここから内陸に向かう幹線道路もほとんどなく、内陸部の都市は概して海沿いの都市よりも規模が小さい。ニューイングランド北部とニューヨーク州のアディロンダック山脈で構成されるこの地域は「迂回された東部(Bypassed East)」と呼ばれている。

「迂回された東部」は幹線道路の近くに、また時にはその両側に位置するが幹線道路そのものには接していない。海上輸送もこの地域を楽に迂回できるため輸送上の一種の空白地域になっていて、その結果、地域経済は成長が鈍化し景気停滞さえ起きている。

ニューイングランド南部は米国大都市圏の一部だが、同北部はほとんど含まれていない。むしろ「カナダの大西洋州」と言った方がはるかに当たっている。

「迂回された東部」はその大部分が美しい自然に恵まれている。ニューハンプシャー州のホワイト山脈にあるプレジデンシャル山地の地形は、米国東部で最も険しいものの1つである。長い海岸線が大西洋に突き出し大波に洗われている。海岸は極めて入り組んでおり、印象的な岬と岩だらけの浜辺に囲まれた入り江とが混在している。アメリカ大陸で最大級の都市からわずか数時間の場所に、ほとんど人の住まない広大な無人地帯が広がっている。

「迂回された東部」はその大部分が美しい自然に恵まれている。ニューハンプシャー州のホワイト山脈にあるプレジデンシャル山地の地形は、米国東部で最も険しいものの1つである。長い海岸線が大西洋に突き出し大波に洗われている。海岸は極めて入り組んでおり、印象的な岬と岩だらけの浜辺に囲まれた入り江とが混在している。アメリカ大陸で最大級の都市からわずか数時間の場所に、ほとんど人の住まない広大な無人地帯が広がっている。

「迂回された東部」の大部分はアパラチア高地が北東部に延びた部分である。しかし、この地域の構造は、一見したところアパラチア南部の尾根と峡谷がはっきり分かれた地形とはほとんど似ていない。

ニューヨーク北部のアディロンダック山脈は、カナダ楯状地が南の方へ延びた一部である。この広大な高地は大陸氷河作用によって大きく侵食された。このため表面は概して角張っているというよりも丸みを帯びている。アディロンダック山脈は標高がそれほど高くないが、この高地の面積はかなり広がっている。

広大な台地がニューイングランドの大部分を占めている。ここは地理学的に見て古く、また水と氷の流れによって激しい侵食も受けている。その結果、この地域の標高は1,500メートルを超えることがほとんどない。大陸氷河によって広い範囲で浸食を受けたため、大地全体の丘や山のほとんどが丸くなっている。そして氷河が届かないほど高い高地にだけ険しい山々を見ることができる。

ニューイングランド北部には、バーモント州のグリーン山脈とニューハンプシャー州のホワイト山脈という2つの山岳地帯がある。標高はグリーン山脈の方が低く、最も高いところでも1,500メートル未満で山頂は丸くなっている。対照的にホワイト山脈は1,900メートルまで達し、山頂近くの斜面は岩だらけで険しい。

さらに南に下った高地が流水で激しく侵食された場所には、その北側にある大きな山岳地帯から大きく離れて複数の峰が突き出している。そのうち最大のものがニューハンプシャー州南部のモナドノック山である。「モナドノック」とは、周りの岩が水の侵食によって取り除かれたことにより低い孤立した山となった硬岩地域の総称である。メーン州中部には同じように印象的なモナドノックであるカターディン山が景観を支配している。

ニューイングランド北部(ニューヨーク州を含む)を特徴付けているのはこれらの山々だが、人々は谷間や低地に家を持ち生計を立てている。そのうち最大級の居住地はニューハンプシャー州とバーモント州の間のコネチカット川流域、バーモント州とニューヨーク州の州境沿いのシャンプレーン湖低地、メーン州北部のアルーストゥーク川流域である。これより小さな低地が海岸線に沿って多数存在し、無数の小川が台地全体の至るところに切り込みをつけている。

「迂回された東部」は、北極と大陸と海洋のそれぞれの気象系が合流する場所であるため暑くなることはほとんどなく、しばしば寒冷でたいていは湿度が高い。アメリカ大陸の東側に位置することから偏西風が大陸性の気象条件をこの地に運んでくるため、海からの影響をあまり受けないことが多い。沿岸部と内陸部の気候は大きく異り、内陸の標高の高いところほどさらに増幅している。

「迂回された東部」に沿って南に流れているラブラドル海流は冷たい。まだ夏が終わっていなくても、よほど勇敢でない限りこの冷たい水に長い時間つかっていたいとは思わないだろう。それでも沿岸の気候条件は、海に近いせいで非常に温暖である。沿岸地域での農業の耕作期間は、内陸部の平均である120日より70日も長い。沿岸部の真冬の平均気温は、近隣の内陸部よりも3℃から6℃高いことが多い。逆に、真夏の気温は内陸部のほうがわずかに高い。

海洋の影響で特に南部の沿岸部に雲や霧が出やすく、夏期には気温がさらに下がる。従って、夏の暑さと日光を必要とする作物を育てるのは難しい。

雨量はこの地域のほぼ全域で豊富で、年間降水量は1000ミリメートルから1500ミリメートルになる。通常、降水量は1年を通じて平均している。概して降雪量は多く、ほとんどの場所で総降水量の25%から50%を降雪から得ている。最もよほど勇敢でない限りこの冷たい水に短い時間でもつかっていたいとは思わないだろう。内陸の場所での年間降雪量は平均250ミリメートル以上である。沿岸部での冬の積雪はまばらで頻繁に雪が解けて地面がむき出しになるが、内陸部の土地は毎冬3カ月から5カ月間雪に覆われる。

「迂回された東部」は住むにも働くにも気楽な場所ではない。厳しい気候、険しい地形、そしてやせて岩だらけの土壌のため少数の特に恵まれた場所以外では農業の機会が限られている。最近まで大規模な鉱物資源の鉱床はほとんど発見されていなかった。それに加えて地域の市場が小さく、また比較的隔離された場所にあることから製造業の発展が阻害されてきた。従って、この地域ならではのいくつかの利点が相対的により重要な意味を帯びてくる。

この地域は常に「迂回された東部」だったわけではない。大西洋に大きく突き出た岬状の土地柄だけに、この地方の海岸はヨーロッパからの探検家や移民が最初に出合う「新世界」だった。17世紀の半ばまでには、メーン州中部・南部にある小さな港の多くにイギリス人が村を作った。18世紀の中ごろまではアメリカン・インディアンがいたため、開拓地は内陸部まで進むことができなかった。

初期のヨーロッパ系移民にとって、メーン州沖合の豊かな漁場である浅瀬はすぐに重要な場となった。大陸棚のすぐ外側に位置する深さ30メートルから60メートルの堆は魚が豊富である。浅瀬であるため、海のかなりの深さまで日光が届き、多くの魚にとって不可欠な餌であるプランクトンの成長が促される。タラやハドックのような冷水魚が豊富である。この資源を利用して、初期の移民たちは塩漬けタラを大量に輸出し始めた。

この地域のもう1つの主要資源は樹木だった。ニューイングランドの森林の大半は、ストローブマツ(松)が占めていた。これは巨大な木で、高さ60メートル以上にまっすぐ伸びる。その材木は節がなく、軽くて丈夫で切るのも容易だった。今は原生林がほとんどなくなってしまい、残っている二次林や三次林はこれと比べて背が低く規模も小さい。森林資源を有していたことから、メーン州は造船業の中心地域となった。

農業は初期の移民が就いた主要な職業の3番目だったが、一般的に農場の規模は小さく収穫量も限られていた。初期の農業は主に自給が目的だった。

ニューイングランド北部で農業の発展がピークを迎えたのは、おそらく19世紀に入った直後である。しかし、米国の別の場所で2つの新たな事態が起きたため、最初は少人数で、やがて大挙して、人々は自分の農場を捨てるようになった。その1つは西部の開拓だった。19世紀の初め、開拓はアパラチア山脈を越えて五大湖の南にある肥沃な農地まで進んだ。2つ目はその後1820年代になって、エリー運河が作られ、さらにその西にも別の運河が建設されたため、西部の農民が東海岸の市場にアクセスしやすくなったことである。貧しいニューイングランド北部の農家はオハイオやインディアナのような場所から運ばれる作物に押され、わずかながら持っていた市場を急速に失った。ニューイングランドの人々は悪い農地を捨て、良い農地を得るために西部への開拓団に加わった。

この地域の農業は1700年代末から1800年代初めにかけての時期に再度打撃を受けた。米国の産業革命発祥の地であるニューイングランド南部で、製造業が発展したためだった。工業の発展によって労働力の需要が大きく高まった。この需要を最初に満たしたのが、製造業での雇用がもたらす高い賃金と安定した収入を求めたニューイングランドの農民たちだった。特に繊維工場で子どもや女性の雇用が増えた結果、農業よりも製造業の仕事の方が価値がさらに高まったのである。

農業の衰退は過去150年間、「迂回された東部」のほとんどの地域で続いている。今日では、ニューイングランド北部の3つの州で農地となっている土地は全体の10%未満である。100年前は50%に近かったのである。つい10年から20年前までニューイングランド北部の多くの町では、人口の減少傾向は1世紀以上も続いた。農業は丘陵地帯から退き、その斜面は次第に森林へ戻っていった。河川の流域も土壌が痩せすぎていることが多く、気候が寒すぎ、農地も狭すぎるため農業生産は成功しなかった。

「迂回された東部」で今でも農業が重要な産業であるところでは、農業に適した少数の場所で集中的に単作農業を行っていることが多い。例えば、メーン州北東部のワシントン郡は、その酸性土壌を活かして米国有数の野生ブルーベリー栽培地域となっている。

農業は多数の土地で行われているが、中でも特筆に値する盛んな農作地域が2つある。1つは、メーン州北東部とニューブランズウィック州(カナダ)西部のセントジョン・アルーストゥーク川流域である。この地域のシルト(砂泥)質・ローム土壌はジャガイモの栽培に最適だが、耕作期間が短いことから、質の高いジャガイモ作りが盛んとなり、ほかの場所では種芋として広く使われている。そして大規模な機械化農法が圧倒的に多い。

しかしジャガイモの市場需要が減少したことや、消費者の嗜好が西部の農家産のジャガイモに移ったことから、同流域のジャガイモ農家は過去数十年間、困難に直面してきた。その結果、今日では主としてメーン州南部・中部の大規模農家が主に生産する家禽類や鶏卵が、同州の農業収入の半分を占めるようになった。これは、ジャガイモ収入の2倍にあたる。

特筆すべき2つ目の地域はシャンプレーン湖周辺の低地である。ここは「メガロポリス」に近いことから、遠隔地と比べて、牛乳の販売における市場優位性がかなり高い。牛乳は比較的かさばるが、生産コストが低い農産物であり、腐りやすく長期の保存が利かない。シャンプレーン低地は、ニューヨーク市とボストンの両方に牛乳を供給している。この地域は夏にそれほど暑くならず、湿気もあるため、飼料作物の栽培に適した気候条件に恵まれている。涼しい夏は、乳牛の飼育にも適している。

バーモント州は、人口1人当たりの乳製品の生産で、長らく米国の首位を独走している。酪農業は同州の農業の90%を占め、その多くはシャンプレーン低地で行われている。

「迂回された東部」の大半は森林の中にある。したがって、ここに大規模な木材製品産業がないと聞くと、意外に感じるかもしれない。しかし、初期に野放しの伐採が行われ、組織立った再植林作業が不十分だったため、原生林に替わって作られた森林の多くは、材木用としても、パルプ用としても、品質が落ちてしまう。

このように木材製品の生産は限られているが、例外はメーン州北部のパルプ材の生産である。米国東部で足を踏み入れるのが最も難しいこの広大な地域では、少数の個人所有者がほとんどの土地を保有しており、森林産業が今でも重要であることに変わりはない。

漁業もまた、問題は多いが、「迂回された東部」の経済の重要な一部である。メーン州のロブスター漁獲高は、米国のロブスター総漁獲高のおよそ80%から90%に相当する。同州はイワシの製品の生産でも首位に立つ。

この地域の海洋漁業には2種類ある。最も重要な沿岸漁業は小型船を使って行い、比較的少額の設備投資しか必要としない。漁獲の売上高が最も高いのはロブスターとタラである。沖合の堆で行う遠洋漁業には、大型船と多くの設備投資が必要である。堆で捕獲する魚はほとんどがタラ、カレイ、オヒョウのような深海魚である。

沖合漁業は、米国の国産石油の需要が高まったため、このところ脅威にさらされている。海底油田の採掘により、米国の豊かな漁場に、海洋汚染が発生する懸念があるにもかかわらず、内務省は1979年、石油会社数社に探査権を付与してしまった。その結果、大量の石油・天然ガス資源が見つかっている。

「迂回された東部」における鉱業は、沖合の石油・天然ガスの採掘以外は、現在あまり重要な産業ではない。しかし、常にこのような状況だったわけではない。鉄鉱石の採掘はアディロンダック山脈で100年以上も続いている。まだ豊富な埋蔵量が鉱床に残っているが、総産出量は比較的少ない。

ニューイングランド北部は火成岩や変成岩に恵まれているため、この地域は長年にわたって建築用石材の重要な産地となってきた。バーモント州中部やメーン州の中部海岸線に沿って多数の花崗岩採石場が操業している。バーモント州は大理石の産出でも全米随一の州である。これらの岩石すべての価値はアメリカ大陸のほかの場所で行われている鉱物産業と比べれば低いものの、バーモント州とメーン州の経済にとっては重要な要素の1つである。

「迂回された東部」ではわずかな差で都市居住者が多い。しかし、この地域には大きな都市部というものがほとんど存在しない。ニューイングランド北部で最も大きな都市は、バーモント州のバーリントンとメーン州のルーイストンであり、いずれも人口はおよそ4万人である。

この地域の主な中心地の規模が小さいことが、この地域の1人当たりの所得水準が比較的低い理由を、恐らく如実に物語っている。米国で高収入の職業は、そのほとんどが都市に基盤を置くが、この地域にはその都市型の職業が少ない。人口的には、全体の半分以下だが、伝統的に米国で低賃金と言われている第一次産業の職業に就いている労働者の比率が高い。大きな地域市場が存在せず、主要都市部への交通が不便だということは、他の地域と違って第一次産業が幅広い製造業経済の発展を支える基盤としての役割を果たしてこなかったということである。

しかし、ニューイングランド北部で経済成長が期待されそうな要因もある。1980年の米国国勢調査によると、南部と西部を別にすれば、成長率が全国平均を上回ったのはメーン、ニューハンプシャー、バーモントの3州だけだった。1980年代、ニューハンプシャー州は全国平均をかなり上回る成長を続け、バーモント州とメーン州は、平均をわずかに下回っただけで済んだ。

地域の人口の動向がこのように変化した理由は、いくつか考えられる。1つは、「メガロポリス」が次第に北へ拡大したことが挙げられる。「メガロポリス」の都市が拡大し、新たな周辺地域が都市化してその一部になると、人々は、さらに大都市から離れた場所に住居を求める。こうして「メガロポリス」の周辺部は着実に拡大し、ニューイングランドを北上してきたのである。

ニューイングランド北部には、多数の製造施設も新たに集まってきているが、その多くは中規模の労働力を必要とする軽工業である。工場がこの地域に集まってきた理由の1つとしては、小都市や田舎の環境の方が住みやすいと雇用者や労働者が考えたことが挙げられる。また、1960年代に、この地域にはいくつかの州間高速道路が建設され、交通の便も大きく向上した。

20世紀半ば以降は、観光業がニューイングランド北部の急成長産業となってきた。釣り、スキー、カヌー、そして美しい風景を楽しむためだけのドライブなどが、観光産業の成長を支えている。

アディロンダック地域の経済も、観光業に大きく依存している。1932年と1980年の冬季オリンピック開催地であるレークプラシッドはスキーに適した多くの地域の1つにすぎない。ニューヨーク州政府は、米国最大の州立公園であるアディロンダック州立公園を通じてこの地域の大半を管理している。

富裕階級が休暇を過ごすための別荘が海岸沿いや湖の周囲に立ち並び、また山中にも点在していて、その数は増えている。所有者がここにいるのは1年の数カ月または数週間だけで、残りの期間はできるだけ長く賃貸して別荘の購入費と維持費の足しにする。ニューイングランド北部の多くの郡では常時人が住んでいる家よりもこのような一時的な住居の方が多くなっている。

最後に、メーン州の沿岸地域の多くの集落やバーモント州、ニューハンプシャー州の小さな大学町、そしてこの地域全体に存在する古い村々は現役を引退した人たちが集まる場所として人気が高まっている。

*上記の日本語文書は参考のための仮翻訳で、正文は英文です。

The Bypassed East

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, An Outline of American Geography.)

The Bypassed East

By Stephen S. Birdsall and John Florin

A map of America's eastern seaboard reveals a lack of large cities along the coast north of Boston. Few major overland routes extend inland from this coast, and interior cities are generally smaller than those along the ocean. This area, comprising northern New England and the Adirondacks of New York, can be referred to as the Bypassed East.

The Bypassed East is near, even astride, major routeways, but not on them. Ocean transportation can easily bypass the region, putting it in a transportation shadow that has produced slow regional economic growth and even stagnation.

Southern New England is a part of metropolitan America. Northern New England, for the most part, is not. It is much more like Canada's Atlantic Provinces.

THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

Much of the Bypassed East is beautiful. The Presidential Range in the White Mountains of New Hampshire contains some of the most rugged topography in the eastern United States. The extensive shoreline thrusts out into the Atlantic and meets the ocean's waves with a heavily indented coast that mixes dramatic headlands with many small coves bordered by rocky beaches. Large empty areas, almost totally lacking in settlement, are only hours away from some of the largest cities on the continent.

Most of the Bypassed East is a part of the northeastern extension of the Appalachian Uplands. However, the structure of the area bears little surface resemblance to the clearly delineated ridge and valley system of the southern Appalachians.

The Adirondacks, in northern New York, are a southern extension of the Canadian Shield. This broad upland was severely eroded by continental glaciation, so that the surface features are generally more rounded than angular. Although elevations in the Adirondacks are not great, the areal extent of this highland is considerable.

A large upland plateau covers most of New England. This upland is old geologically and has also been heavily eroded by moving water and ice. One result is that elevations throughout the region seldom top 1,500 meters. Widespread scouring by continental glaciers rounded most of the hills and mountains across the plateau. Only where elevations were high enough to remain above the moving ice can one find more rugged mountains.

The two major mountain areas of northern New England are the Green Mountains of Vermont and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The Green Mountains are lower in elevation, less than 1,500 meters at their highest, and their tops are well rounded. The White Mountains, by comparison, rise to 1,900 meters, and their upper slopes are rugged and steep.

Farther south, where the upland plateau has been heavily eroded by flowing water, several isolated peaks stand well apart from the major mountain areas to the north. The largest of them is Mount Monadnock in southern New Hampshire. Monadnock is a name given to all such areas of hard rock that have become low, isolated mountains as the surrounding rocks were removed by water erosion. Mount Katahdin, an equally dramatic monadnock, dominates the landscape of its portion of central Maine.

Although northern New England (with New York) draws character from its mountains, its people find their homes and their livelihoods in the valleys and lowlands. The largest such areas are the Connecticut River Valley between New Hampshire and Vermont, the Lake Champlain Lowland along the northern Vermont-New York border, and the Aroostook Valley in northern Maine. A number of smaller lowlands border the seacoast, and innumerable streams have sliced the plateau throughout the area.

The Bypassed East is a place where polar, continental, and maritime weather systems meet, and the result is a climate that is seldom hot, often cold, and usually damp. Because of its location on the eastern side of America, the wind systems tend to push continental conditions into the area and to limit the maritime impact on the location. The substantial climatic difference between coast and interior is further increased by higher inland elevations.

The Labrador Current that flows southward along the Bypassed East is cold. Even in late summer, only the most intrepid swimmers are willing to dip themselves into its waters for more than a short time. Still, the climatic conditions along the coast are moderated substantially by proximity to the water. The growing season near the coast is as much as 70 days longer than the interior average of 120 days. Average midwinter temperatures at coastal sites are often 3° to 6°C higher than at nearby interior locations. Midsummer temperatures, in contrast, are slightly higher in the interior.

The maritime influence brings frequent cloud cover and fog, particularly along the southern coastline, which serve to cool temperatures further during the summer. It is consequently difficult to grow crops that require summer heat and sunlight.

Almost all parts of the region receive substantial precipitation, usually between 100 and 150 centimeters annually. Precipitation is usually scattered evenly throughout the year. Snowfall is generally substantial, with most places receiving between 25 and 50 percent of their total moisture in the form of snow. Most interior locations average at least 250 centimeters of snow annually. Winter snowcover near the coast is sporadic, with frequent thaws and bare ground, but snow covers the ground inland for three to five months each winter.

POPULATION AND INDUSTRY

The Bypassed East is not an easy place in which to live and work. Its harsh climate, hilly terrain, and thin, rocky soils limit agriculture, except in a few particularly blessed locations. Few mineral resource deposits of substantial size have been found until recently. Coupled with a small local market and relative isolation, this has limited the development of manufacturing. The advantages that the area does offer thus become relatively more important.

This was not always the Bypassed East. Its foreland location, jutting far out into the Atlantic Ocean, meant that its shores were among the first parts of the New World encountered by European explorers and settlers. By the mid-17th century, many of the small harbors of central and southern Maine housed British villages. Settlement was kept out of the interior by the American Indian population until the middle of the 18th century.

To the early European settlers, the rich fishing banks off the coast of Maine were immediately important. The banks, shallow areas 30 to 60 meters deep in the ocean at the outer margins of the continental shelf, underlie waters that are rich in fish. Their shallowness allows the sun's rays to penetrate easily through much of the water's depth, which encourages the growth of plankton, a basic food for many fish. Cold-water fish, such as cod and haddock, are abundant. Using this resource, the early settlers began a substantial export of salted cod.

The other prime resource of the region was its trees. The white pine was dominant in the forests of New England. A magnificent tree, it reached heights in excess of 60 meters and stood straight. Its wood was clear, light yet strong, and easily cut. Almost all of the virgin forests are gone now, and the second- and third-growth forests that remain are short and insignificant in comparison. Forest resources allowed the state of Maine to become a center for ship construction.

Agriculture was the third major occupation of the early settlers, but farms tended to be small and production limited. Early farming was primarily a subsistence activity.

The peak of agricultural development in northern New England probably came just after the start of the 19th century. But two developments elsewhere in America soon began to pull people off their farms, first in a trickle, then in droves. One was the opening of the West. Settlement moved beyond the Appalachians onto the rich farmlands south of the Great Lakes early in the century. Then, in the 1820s, the construction of the Erie Canal, and later other canals farther west, made the markets of the East Coast more accessible to western farmers. The poor farms of upper New England rapidly lost what little market they had to crops imported from places like Ohio and Indiana. New Englanders left their farms and joined the migration westward, exchanging bad land for good.

A second blow to the region's agricultural fortunes also occurred during the late 1700s and early 1800s with the development of manufacturing in southern New England, where the Industrial Revolution began in the United States. Industrial growth created a great demand for labor. That demand was first met with New England farmers seeking the higher wages and steady income offered by manufacturing employment. An increase in child and female labor, particularly in the textile mills, further enhanced the value of manufacturing work over farming.

Agricultural decline has continued across most of the Bypassed East for the last 150 years. Today, less than 10 percent of the land in the three states of northern New England is in farms; 100 years ago, the amount was closer to 50 percent. Until the last decade or two, many northern New England towns had patterns of population decline that lasted for a century or more. Farming retreated off the slopes, allowing them to return gradually to forest. Even in the valleys, soils were often too infertile, the climate too cold, and the farms too small for successful agricultural production.

Where farming in the Bypassed East remains important, it tends to specialize in single-crop production and to be concentrated in a few favorable locations. For example, the acid soils of Washington County, in northeastern Maine, support one of America's major centers of wild blueberry production.

While agriculture is found in a number of other locations, two significant areas of agricultural production in the region deserve special notice. One of these is the St. John-Aroostook Valley, an area of northeastern Maine and western New Brunswick (in Canada). The area's silty loam soils are ideal for potato growth, and the short growing season encourages a superior crop that is used widely elsewhere as seed potatoes. Large-scale, mechanized farming predominates.

The valley's potato growers have gone through a difficult period during the past several decades as a result of a declining market demand for potatoes and a preference on the part of consumers for the potato products of Western growers. As a result, poultry and eggs, mostly from large producers in south-central Maine, now account for half of the state's agricultural income--double the potato's share.

The second area is the Lake Champlain Lowland, whose proximity to Megalopolis gives it a substantial market advantage over more distant areas for the sale of milk, a relatively high-bulk, low-cost product that spoils easily and cannot be stored for any extended period. The Champlain Lowland supplies milk to both New York City and Boston. The area's summers are mild and moist, a climatic condition that encourages the growth of fodder crops. These cool summers are also well suited to dairy cows.

Vermont has long led the United States in the per capita production of dairy products. Dairy farming accounts for 90 percent of the state's agriculture, and much of it is found in the Champlain Lowland.

In much of the Bypassed East, the land is in trees, so lack of a large-scale wood-products industry may be somewhat surprising. However, earlier uncontrolled logging and limited organized reforestation meant that much of the forest that replaced the original trees is of poor quality for both lumber and pulp production.

An exception to this pattern of limited output is the pulpwood production of northern Maine. Here, on some of the most inaccessible large tracts of land in the eastern United States--where a small number of private owners control most of the land--forest industries remain important.

Fishing also remains an important, if troubled, part of the economy of the Bypassed East. Maine lobstermen account for about 80 to 90 percent of the total U.S. lobster catch, and the state also leads in sardine production.

There are two kinds of ocean fishing in the region. Inshore fishing, the most important, uses small boats and requires a relatively small capital investment, with lobsters and cod the most valuable catch. Deep-sea fishing on the banks off the coast requires far larger boats and more capital investment. Most fish caught on the banks are bottom feeders such as cod, flounder, and halibut.

Offshore fishing has recently been threatened by the high demand for domestic petroleum in the United States. Fears of pollution from offshore oil drilling in the country's rich fishing banks were overruled in 1979 when the Department of the Interior granted exploration leases to several oil companies, and major resources of petroleum and natural gas have been discovered.

Mining other than for offshore petroleum and natural gas in the Bypassed East is not currently of great importance. This was not always the case. Iron ore has been mined in the Adirondacks for more than 100 years, and the reserves there are still substantial, but total output from the mines is relatively small.

The igneous and metamorphic rocks of northern New England have made the area an important producer of building stone for years. Many granite quarries operate in central Vermont and along the central coast of Maine. Vermont is also the leading marble-producing state in the United States. The value of all of these rocks is small compared to the minerals industries found in other parts of the continent, but it is still an important element in the economy of the two states.

CITIES AND URBAN ACTIVITIES

By a slight majority, most of the residents of the Bypassed East are urbanites. However, the region contains few substantial urban areas. The two largest cities of northern New England are Burlington, Vermont, and Lewiston, Maine, both of which have about 40,000 residents.

The small size of the major regional centers is a good indication of what may be the greatest single reason for the relatively low per capita income levels found in the region. Most higher-income occupations in the United States are urban based, and this area lacks urban occupations. Although they are less than half of the total, a high percentage of the work force is engaged in primary occupations, which are traditionally among the lowest paying in America. The absence of a large local market and poor access to major urban areas means that primary industries have not served as the foundation for the development of a more broadly based manufacturing economy as they have elsewhere in the United States.

Nevertheless, there seems to be reason to anticipate that the economy will grow in northern New England. The 1980 U.S. census indicated that Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont were the only states outside the South and West to grow at a rate above the national average. In the 1980s, New Hampshire continued to grow at a rate well above the national average, and Vermont and Maine were only somewhat below the average.

There seem to be several reasons for this shift in regional population fortunes. One is the gradual northward growth of Megalopolis. As the cities of the urban region expand, as new peripheral areas urbanize and become a part of urban America, and as people search farther outward to find residences away from the large cities, the Megalopolitan periphery has been pushed steadily northward in New England.

Northern New England is also attracting a number of new manufacturing facilities, which tend to be light industry with medium-sized work forces. In part, they are locating in the region because the employers and their workers find the small-town and rural environments to be good places to live. Also, the construction of several interstate highways into the region during the 1960s has provided greater accessibility.

Tourism has been northern New England's boom industry since the mid-20th century. Fishing, skiing, canoeing, and just driving around looking at the beauty of the place – all of these are a part of this tourist growth.

The economy of the Adirondacks area is also heavily dependent on tourism. Lake Placid, home of the 1932 and 1980 Winter Olympics, is but one of many ski areas. The state of New York oversees much of the area through its Adirondack State Park, America's largest state park.

Strung along the seashores and around the lakes, and strewn across the mountains, is a growing collection of vacation homes – second homes for the well-to-do. They are occupied by the owners for a few months or a few weeks each year and then rented for as much of the rest of the time as possible to help pay the purchase and upkeep costs. In a number of the counties of northern New England, there are more of these part-time dwellings than there are permanently occupied houses.

Finally, many of the coastal communities of Maine, the small college towns of Vermont and New Hampshire, and old villages throughout the region have become popular retirement centers.

[Stephen S. Birdsall is dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Michigan State University and is the co-author of four books and atlases, including Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada.]

[John Florin is chair of the geography department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Pennsylvania State University. His recent publications include Atlas of American Agriculture: The American Cornucopia with Richard Pillsbury and Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada with Stephen S. Birdsall.]