国務省出版物

米国の地理の概要 – 「メガロポリス」

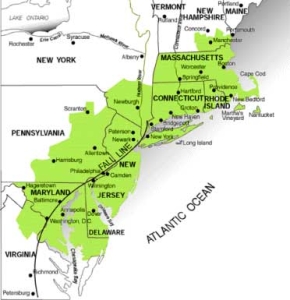

1961年、1人のフランス人地理学者が、米国北東部の都市化が進んだ地域に関する記念碑的な研究成果を発表した。ジャン・ゴットマン(Jean Gottmann)教授は20年を費やして、ニューハンプシャー州南部およびマサチューセッツ州北部からワシントンD.C.にいたる地域を研究した。そして、この一帯は「非常に特殊な地域」であると結論づけ、「メガロポリス」(Megalopolis)と命名したのである。

メガロポリスエリア

「メガロポリス」は、北東部の沿岸に隣接する独立した広大な大都市圏が次第に融合することによって形成された。これらの大都市の人口が増加するに従い、その影響は周辺のより小さい地域に波及していった。こうした大きなリング状の郊外地域は、それ自身都市のスプロール化を進めた。そうして生まれた大都市圏の外縁部分が最終的には相互に融合し始め、遂には広範な都市化地域が形成されることとなった。

「メガロポリス」の最大のテーマは「都市性」(urban-ness)である。程度の差こそあれ、都市サービスはこの地域に住む数百万の人々の生活を支えている。そうした都市の形態には大きな差異はない。オフィスビルやアパート、小規模店舗や大型ショッピングセンター、工場、精製所、住宅地、ガソリン・スタンド、ハンバーガー・ショップなどが数え切れないほど立ち並び、その合間には船や鉄道、トラックで運び込まれた商品を一時的に保管する倉庫がある。そしてこれらすべてがこの地域の800キロメートルにわたって並んでいる。

一方、「メガロポリス」にはたくさんの緑地も存在する。レクリエーションに使える公園などの場所があるし、優に300万ヘクタール以上の土地が農地に利用されている。

「メガロポリス」には様々な特徴があるが、この地域が米国できわめて重要な位置を占める理由は都市地域として大きな存在感を持つからである。1990年時点で人口が100万人を超える46の大都市圏のうち、10カ所は「メガロポリス」にあった。この地域は米国の総人口の17%を占めるが、面積ではわずか1.5%に過ぎない。

1人当たりの平均所得は高くホワイトカラーおよび専門職に就く居住者の比率は全米平均よりも高い。輸送と通信の活動はきわだって大きい。その理由の1つは、この地域が持つ海岸沿いの立地条件にある。民間航空の国際線を利用する旅客のおよそ40%は「メガロポリス」内の空港から出発している。さらに、米国の輸出量の30%近くが「メガロポリス」の6つの主要港を経由している。

米国の中でもこの特定の地域がこうした発展を遂げたのはなぜなのか。こう質問されたら、通常、地理学者が最初に考えるのはその位置である。実際「メガロポリス」の場合には、この広大な都市地域の位置と立地条件がその起源と成長の謎を解く鍵になる。

この地域の輪郭線を見ると、立地上様々な特徴があることが見て取れる。「メガロポリス」は海岸線に沿って位置しているため、その東端は複雑に入り組んでいる。多数の半島が大西洋に突き出している。島々が海岸に沿って散在しており、そのうちいくつかは、形成された地域社会を支えられるほど大きい。陸地が生みに突き出しているのを、そのまま鏡に映したような形で、湾や河口が陸地に入り組んでいる。このように陸地と海が相互に入り組んでいるため、陸地と海がより接近することになる。かくして、直線的な海岸線よりも安いコストで水上交通を利用する機会がはるかに大きくなる。

勿論、質の高い港も必要である。「メガロポリス」には、米国有数の天然港がいくつか存在する。直近の大陸氷河期に、「メガロポリス」の北半分は氷に覆われていた。その氷が解け始めると、河川の広い方水路ができ、川の浸食力によって平坦な海岸平野には深い溝が刻み込まれた。海水面が上がると、それより低い川谷は「溺れ」て河口を形成し、海岸線が内陸にいり込んだ。こうした氷河作用による川谷が、後にメガロポリスの発展に役立つこととなる港湾のいくつかを形成したのである。

このほかにも、1,2か所の地域に限定して、氷河期は大きな痕跡を残している。氷河の拡大によって大量の土壌や石や、その他の破片がすくい上げられた。そして氷河の前線が後退するに伴い、これが氷堆石として残された。氷河の後退によって、現在のコネチカット州沿岸地方のちょうど南側に、一連の尾根が残された。海水面が上昇すると、こういった氷堆石が島になり、海からの堆積物によって面積が拡大した。しかし、島の幅が広がらなかったため、この島は「ロングアイランド」と名づけられた。それいがいに呼びようがない形だった。

ロングアイランドは、大きく言って2つの点でニューヨーク港の質の向上に貢献してきた。第一に、港湾施設に利用できる海岸線は、ハドソン川に沿ってすでにかなり長かったが、それがさらに大きく延長される形になった。第二に、十分に発展した広大な港の周辺に都市部が拡大すると、より広いスペースが必要になる。潮汐湿地と浸食に耐えたパリセーズ峡谷の尾根のせいで、ニューヨーク都市部の拡大に適応できる良質の土地は、ハドソン川から西のニュージャージー州に限定された。ハドソン川の東岸には長細い土地しかなく、これがマンハッタン島である。しかし、イーストリバーの向こうには、ロングアイランドがある。ここはニュージャージーの湿地帯のような障害物がなく、平坦でわずかに起伏のある土地である。ロングアイランドの西端にあるニューヨーク市のブルックリン区とクイーンズ区は、早くから発展した。そしてロングアイランドは、都市部が東に大きく広がる余地を提供したのである。

「メガロポリス」には良質の港が多数あるが、それ以外の立地上の特色としてこの地域の都市経済の発展に大きく貢献したものはほとんどない。夏季は概して農業に十分なほど期間は長く、雨量も多いが、さほど気候が温暖というわけではない。土壌はむらがあり、メリーランド州ボルティモアやペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィアよりも内陸部の土壌の方が、ニューヨークに近い土地のほとんどの土壌よりも上質である。

「メガロポリス」のニューヨークから南の一般的な地形は、都市部の発展にとって有利な立地条件を追加提供する形になっている。大西洋沿岸から内陸に向かって行くと、まず非常に平坦な海岸平野があり、そのあとに起伏のある、時に小高い地形である「ピードモント台地」(Piedmont Plateau)が現れる。不規則に起伏するピードモント台地の下には、非常に古くて固い岩がある。ここの地表は浸食に強いため、ピードモント台地の標高は海岸平野よりも高く維持されている。従って、川がピードモント台地から流れ出る地点の至るところで、地形学的な境界線沿いに、一連の急流や滝が形成されている。この境界線は瀑布線(fall line)とも呼ばれている。

初期の入植者たちは、この瀑布線が航行の邪魔になるが、これが水力源であることも間違いないと思った。入植地は、できるだけ内陸に入ってはいるが、依然として海上輸送にも手近な、瀑布線沿いに発展した。さらに、瀑布線が航海の起点となることがしばしばあったため、内陸に運んだり輸出したりする商品は、瀑布線のいずれかの場所で荷降ろしして、別の輸送手段に移さなければならなかった。これらの場所は、商品を輸出するために内陸部から河川航行の起点へ運ばれる輸出商品によってもまた利益を得ていた。多くの場合、ここで製造業も営まれていた。

北米の中でもこの地域は、ヨーロッパとカリブ海植民地や南米の生産性の高い農場を直接結ぶ海路上に、またはその近くに位置していた。少なくともヨーロッパへの復路は、必ずここを経由した。従って、後に周辺で「メガロポリス」として発展した港は、停泊地として便利だったため、18世紀から19世紀にかけて急速に拡大した大西洋横断貿易に、大きく貢献した。

もう1つ、「メガロポリス」の発展にとって重要な意味を持っていたのが、内陸部に対する中核都市の位置だった。フィラデルフィアとボルチモアが急速に発展したのは、いずれも比較的広く良質な農業地帯の中心に位置していたからである。内陸部への交易路が早い時期に建設されたため、これらの都市の貿易機能の発展を促すことに役立った。ボストンから内陸に向かうと、土壌は(今も変わらないが)余りにも岩だらけで、地形も起伏が多すぎるため、農業には適していない。しかし、ニューイングランドの丘陵地は、造船には理想的と言える広葉樹や松の木で覆われていた。また、非常に生産力の強いニューイングランド沖合の漁場や、さらに南下した豊かななチェサピーク湾も手近にあった。

しかしながら、都市の立地条件を評価するに当たって、交通の便がどれほど重要であるかが最もよくわかるのはニューヨークである。この都市の最大の強みは、アパラチア山脈を通る最良の天然航路の起点に位置している点にある。後年エリー運河によって補強されたハドソン・モホーク河川系や、鉄道、高速道路が、西方の五大湖へつながっており、さらにそこから、広大な内陸部へと行き来することができる。内陸部の平野に入植地が増え、経済活動が活発になるにつれて、大量の生産物がメガロポリスの都市中心部へ運ばれるようになった。こうした取引の増加から最も利益を受けた都市が、もともと内陸部との天然の交通路に最も恵まれていたニューヨークだった。

米国の植民地時代に、ヨーロッパとカリブ海地域とアメリカ大陸を結ぶ三角貿易が盛んになるにつれ、ボルティモア以北の大きな港湾都市で、小規模な製造業が姿を現わし始めた。都市産業が成長するにつれて労働需要が増加し、北西ヨーロッパからの移民を引き寄せた。また多数の労働者が農業から転身したりしたため、これらの都市の人口はふくれ上がった。銀行その他の金融機関が、地元の製造業や海運業への投資を保証した。サービス業、卸・小売業、情報管理の中枢などがそろって成長し、都市の拡大さらに後押しした。そして最大の成長を遂げたのが、ニューヨーク、フィラデルフィア、ボストン、ボルティモアだった。

だがこの地域の最も特異な点は、これらの都市の成長自体ではない。上記4大都市(後に首都ワシントンを加えて5大都市になる)が、非常に近接した位置で成長を続けたことである。もちろん、ワシントンは特異な例である。なぜならワシントンもまた、瀑布線上にはあるものの、中央政府機構の肥大化が、この都市の発展をもたらした直接の原因だからである。他の4都市は、メガロポリスの軸に沿って存在する多数の小都市とともに、経済的刺激に依存する面が大きかった。19世紀における米国全体の成長が余りにも大きく、内陸部とこれら4港の結びつきが余りにも強かったため、4港湾都市のいずれも単独で近隣の港や競合する港へ流入する商品全部を吸収することはできなかった。20世紀の終わりまでには、これら4都市の後背地をすべて総合した経済的資源は、莫大な量に達していた。

「メガロポリス」全体に、地域としての一体感を与えている最も重要な要素が、都市形態と都市機能である。高層ビルや人通りの激しい道路、密集した住宅、そして工場などが、劇場、交響楽団、美術館、大型図書館などの様々な文化的機会と混在している。また時として、老朽化した建物や交通渋滞、大気汚染などの質的劣化も目に付く。これらすべて、そしてそれ以上のものが存在するのが、「メガロポリス」の大都市圏なのである。

これらの特徴は、世界中のほとんどどの大都市でも見受けられる。「メガロポリス」が特別なのは、この地域の都市としての特徴が、中核都市からはるか遠方まで波及しているため、各都市地域が大都市融合プロセスの中で互いに同化し始めたことにある。こうして「メガロポリス」は、きわめて都市的な類型と、都市に特有な諸問題が展開していく様子を非常に広い範囲で観察することができる、一種の巨大な実験室となったのである。

メガロポリスの人口密度は高く、1987年時点で1平方キロメートル当たりの平均は約305人だった。もちろん、周辺の郡部には、人口密度がこの地域平均の10%-20%しかないところもある。都市に近づくにつれて居住地の人口密度は高くなり、都市の中心部近くでは密度は非常に高くなる。例えば、ニューヨーク市では、1987年の人口密度が1平方ヘクタール当たり平均226人を超えていた。これを1平方キロメートルあたりに換算すると、22,660人以上になる。

都市機構の特徴のうち、このような人口密度のパターンと関係しているのは何だろうか。近代の都市は、要するに経済活動が行なわれている場所だから生まれている。ビジネス拠点を都市へ移すことを決めるさいには、基本的には、経済的利点が最大の要因である。この利点はあまりにも大きいため、多くの人々は互いに、しばしば望む以上に身を寄せ合って生活している。都市機構の恩恵を享受するため、多くのマイナス面を辛抱している。

しかしながら、住居を郊外へ移すことによって都市生活の欠点を最小限にしようとする都市生活者も増えてきた。さらに遠い、準郊外地域と呼ばれる地区へ引っ越した者もいる。小さな町やかつての別荘地域、田園地帯の家などに住む準郊外地域居住者は、遠く離れた職場まで通勤する。しかし、このような人口拡散も人口密集のもたらす欠点をすべて解消するには至っておらず、そうした欠点に直面する人々を単に移動させたに過ぎなかった。また人口拡散によって、この地域の居住者の職場も拡散している。大都市人口は無秩序に増えているが、仕事のために都市の中心部に入る必要がある人の割合は、以前よりも減少している。

都市の風景の重要な要素の1つは相互交流である。一般的に言って、何かを移動させるためのコストは、その距離に正比例する。従って、移動コストを最小限にするため、活動は都市に集中する。都市地域では、ある場所からほかの場所へ移動できることが重要である。それは、都市の土地の大部分が相互交流を容易にするために使われていることからも明らかである。道路、地下鉄、橋、トンネル、歩道、駐車場など、人的交流の移動経路はひと目でわかる。「メガロポリス」内の都市のように古くからある都市では、徒歩や馬車で移動していた時代に街の中心部の区画ができあがった。人的交流を促す都市機能に充てられている中心部の面積は全体のわずか35%程度である。自動車が台頭して以降に大部分が発達した新しい都市では、その割合ははるかに高い。

このほかにも、目につく度合は低いが、同じように重要な相互交流の形がある。都市において情報やアイディアの移動が容易なのは、集中して発展した電話、電報、テレタイプなどの通信システムのおかげである。90年前、あらゆる大都市の中心にあるオフィス街には電話網の回線がクモの巣のように張り巡らされ、通信需要の大きさを物語っていた。今日では電話線はケーブルに束ねられ、地下に埋設されている。

おそらく、相互交流が行われる最大の動機は、需要と供給が地理的に離れていることだろう。経済的にみて、ある商品やサービスに対する需要があるのに、その場所ではその需要を満たせない場合には、こういった商品やサービスは別の場所で入手しなければならない。その結果、相互交流が生まれてもおかしくない。

これらの点が、都市の景観にどのような意味合いを持っているかは明らかだろう。比較的狭い区域で、実に多くのさまざまな活動が行われている。1つの場所に集中しがちな機能もあれば、都市部全体に分散する機能もある。都市では様々な活動が行われているため、各機能の間で、あるいはまた同じ機能の範囲内で、相互交流が刺激される。これらの活動を地図にすると、実に雑多な土地利用のパターンが浮かんで来るはずだ。

人口や都市活動が集中すると、支援機能も必要になる。伝統的に市庁のさまざまな部門として組織・運営されるこれらの公共サービス機能は、経済的に見た場合、間接的な生産活動であるとしかいえないものの、商工業にとっては必要なものである。

上水道、電力、下水道、ゴミ収集などのサービスのほかにも、都市は警察や消防、公共交通機関の建設・整備、保健医療、重要な人口統計の作成、教育施設など、多くのものを提供している。

大都市ではこれらのサービスが普及したため、これを管理する巨大な政府組織が発達した。極端な事例を挙げると、1982年にニューヨーク大都市圏で業務を行っていた行政機関の数は1,550を超えていた。

都市の景観に特色を与える大きな要素は、まだほかにもある。それは都市への出入りのしやすさの度合である。都市の組織や構造の上で、各地区間を容易に行き来できるかどうかを、いつも考慮してきたとは限らない。例えば、「メガロポリス」にある多くの都市の市街地図は、17世紀から18世紀にかけて人気のあった、単純な正方形または長方形の格子状になっている。

これらの都市が発展するにつれて、こうした街路形態では往来が不便であることが明らかになった。例えば、格子状の街路だと、直角に交わる交差点が多くなる。交差点のたびに交通の流れが妨げられるため、交通量が増え、そうなると交差点での停止時間も長くなる。1900年までにボルチモアとボストンの人口は50万人を超え、フィラデルフィアは130万人近くに達し、ニューヨークは350万人に近づいていた。自動車の大きな影響が出てくるのはまだ先だったが、これらの都市の中心部では、すでに深刻な交通渋滞が起きていた。

1950年代に入ると、都市の面積の急速な拡大と移動のさいの自動車の利用増をもたらす変化が起きた。都市労働者のうち、中心部から遠く離れた人口密度の低い住宅地に住み始めた人の割合が大きくなった。このため、大量輸送は経済的に不利になった。トラック輸送にはスピードと柔軟性という経済的観点から見た強みがあり、貨物の短距離輸送には鉄道ではなく運送会社が使われるようになった。これに呼応して、交通計画担当者たちは、都市を取り巻く環状幹線と、出入口の少ない大量輸送用の高速道路を建設し、局地的な移動交通と、市街地横断交通や通過交通を区別することを提案した。このような変更は一部成功したが、ほかの要素も加わって、都市中心部内への流入や、中心部と周辺部の交通、そして最終的には周辺部の各区域間の交通に対する需要もまた増大させることとなった。全体的な交通経路がより複雑になり、管理も難しくなった。

このことから、都市の景観のもう一つの特徴が見えてくる。それは変化する景観である。フィラデルフィアやニューヨークのような大都市には、毎年数万人単位で、新しい居住者が転入してくる。これより多くの人が転出するが、遠くの都市へ移る人もいれば、大都市圏の郊外へ引っ越す人もいる。壊される建物もあれば、新たに建設されるものもある。街並みが変わり都市機能の形態も変えられるため、その新しいパターンに合わせて人、モノ、アイディアの流れも変わっていく。

このような変化は米国のどの主要地域でも見られるものかもしれない。だが、ある意味では、まさにこうした変化が「メガロポリス」を作り上げたと言える。

過去40年間で「メガロポリス」が経験した最も深遠な変化は、恐らく主要大都市圏の範囲が大きく拡大したことだろう。住民人口の居住範囲が最も遠くまで広がっていったのがグレーター・ニューヨークであることは明らかだが、ボストン、フィラデルフィア、ボルティモア、ワシントンの各地域も大きく成長した。ニューヨークはもともと人口が最も多く、最も経済が集中していたが、ほかの3つの港湾都市も確固たる成長基盤を持っていた。時を同じくして、連邦政府は機能を急速に拡大していった。そのため公務員の人口と、それに対して食べ物や衣服、その他のサービスを提供する人々も増加したため、コロンビア特別区--ワシントン市とコロンビア特別区は同一地域である--の面積だけでは吸収しきれないまでになった。都市開発は、隣接するバージニアとメリーランドの両州にも波及していった。

市域の境界線を越えて、はるか遠くまで都市人口が広がったことは、「メガロポリス」の田園の生活にも大きな衝撃を与えた。都市人口が増加するにつれて、田園部から運び込まれる食料に頼らなければならない人の数が大きく増えた。「メガロポリス」の都市部に住む数千万の人々が、米国内および海外からの農産物を消費している。しかしながら、都市に近い農地を耕作する人々の多くは、価格が高い食料品や、腐りやすい作物を専門的に生産することを選択した。乳製品や、トマト、レタス、リンゴをはじめ、集約的に生産した様々な「食卓用作物」が「メガロポリス」の田園部で生産される農産物の主流になっていった。

さらに人口密集地と活発な経済活動が、周縁部にまで広がるにつれて、地価が押し上げられた。数十年前に2万ドルで購入した60ヘクタールの農地が、最終的に100万ドルで不動産開発業者に売却されることもありうる。購入した開発業者がその土地を、それぞれ0.2ヘクタールの住宅用地250件分に分割して、公益設備や道路を整備した上で、1区画2万5,000ドルで売れば、総額625万ドルを得ることになる。

例え農家の人々が、こうした農地売却による利益の誘惑に耐えられたとしても、近隣の地域が都市活動に使われるようになると、土地にかけられる税金が都市なみに急激に上昇した。土地の利用を農業に限定するための規制が導入される以前は、こうした農家が農業を続けるには、価値の高い農産物に限った集約的農業以外に道はなかった。

「メガロポリス」における都市部のスプロール化と、それに伴う農業活動の変化は、主要な市街地の間をつなぐ幹線道路に沿って起きた。「メガロポリス」の都市間を行き来する交通量は早くから増加した。大都市で働く人々が住まいだけ移す場合、当然ながら主要オフィス街に行くのが便利な場所を選ぶ割合が多かった。主要な幹線道路と、これには及ばないが、都市の間を走る鉄道や主な支線道路が網の目のように発達し、これに沿って大都市人口の移動がまず始まり、最も遠くまで広がった。その結果、都市部はまず都市間を結ぶ主要道路に沿って一体化していった。そして、交通の便をよくしてほしいとの要求が高まったため、さらに優れた都市間の交通手段が作られることになった。

個々の都市部の人口が増加するにつれて、人口構成も変化した。1910年以前には「メガロポリス」の都市は多数のヨーロッパ系移民を受け入れていた。これらの移民たちは、「メガロポリス」にある大きな港のいずれか--通常はニューヨーク港--から入国していた。さらに西の中西部や「グレートプレーンズ」の農業地帯や都市部へ向かった。しかし、向かわなかった人々は、「メガロポリス」の都市の一画に集団で住みつき、たいていは国籍ごとコミュニティを形成した。

第一次世界大戦がヨーロッパで勃発すると、移民の流入が止まり、新たに別の 移民が、「メガロポリス」に流入し始めた。それまではわずかだった南部諸州からの黒人の移住が増加し始めたのである。黒人移住者と、南部の田舎から出てきた白人グループが、以前のヨーロッパ系移民グループと同じパターンで定住した。黒人の多くは、都市の中の、すでに少数の黒人が住んでいた地域に根を下ろした。

黒人の移住は20世紀半ばまで続いたので、人口密度も高まり、もともとの居住中心地から外へ向う拡大が生み出された。黒人人口は、内部で何十年にもわたって増加した後、しばしば黒人居住地周辺部でも黒人の人口密度は高くなり始めた。

近年、まったく新しい2つの局面で都市が変化した。この変化は、全米規模で起きていると言えるかも知れないが、最も劇的だったのは「メガロポリス」の港湾都市のような、最も大きくて古い都市でだった。

第一は、1960年代後半、米国の歴史で初めて、大都市圏--中心となる都市とその郊外を合わせた地域--から脱出する人の数が、転入する人の数を超えたということである。大都市圏からの脱出組みの落ち着き先は、一般的に言って、主に小都市や町やその間にある田園地帯だった。

第二は、大都市圏の多くの場所で、高層のオフィス・ビルが急激に増えたことだ。新しい金属やガラス板でできた高層オフィス・ビルの出現によって、1970年代以降、米国の多くの都市では、中心部の高層ビルが空を背に描く輪郭(スカイライン)が大きく変貌した。しかし、この変化は、もはや昔の都市中心部に限ったことではない。巨大なオフィス街が、郊外にも出現し、その多くは、大都市中心部よりも広いオフィススペースを持っている。一見したところ、この変化によって最も大きな影響を受けたのは、自宅のある場所ではなく、職場の場所と通勤パターンのようである。

明らかに都市部の特色は景観の変化である。そして「メガロポリス」で起きている変化は、この地域の特異な性質にふさわしいものである。「メガロポリス」の変化は連続的であり、激烈だった。その変化の規模は世界のどこにも類をみないものだったのである。

*上記の日本語文書は参考のための仮翻訳で、正文は英文です。

Megalopolis

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, An Outline of American Geography.)

Megalopolis

By Stephen S. Birdsall and John Florin

In 1961, a French geographer published a monumental study of the highly urbanized region located in the northeastern United States. Professor Jean Gottmann spent 20 years researching the area extending from southern New Hampshire and northern Massachusetts to Washington, D.C. He argued that this was a "very special region," and he named it Megalopolis.

Megalopolis was formed along the northeastern coast of the United States by the gradual coalescence of large, independent metropolitan areas. As the populations of these cities grew, the effects of growth spilled over into the surrounding rings of smaller places. Larger suburbs in these rings made their own contributions to the total urban sprawl. The outer fringes of the resultant metropolitan regions eventually began to merge with each other to form an extensive urbanized region.

The dominant theme of Megalopolis is "urban-ness." In varying degrees, urban services provide for the millions who live in this region, and urban forms are never far away. There are office and apartment buildings, small shops and mammoth shopping centers, factories, refineries, residential areas, gas stations, and hamburger stands by the thousands – interspersed with warehouses to store temporarily the goods brought by ship, rail, and truck – all this along the region's 800-kilometer route.

But Megalopolis also contains many green spaces. Some are parks or other land available for recreation; well over 3 million hectares are devoted to farming.

In spite of the mixed character of Megalopolis, it is its massive urban presence that makes this region so important in the United States. Ten of the country's 46 metropolitan areas exceeding 1 million population in 1990 were located in Megalopolis. The region holds 17 percent of the total U.S. population – in only 1.5 percent of the area of the country.

Average per capita income is high, and a higher than average proportion of its residents work in white-collar and professional occupations. Transportation and communication activities are prominent, partly a result of the region's coastal position. Approximately 40 percent of all commercial international air-passenger departures have Megalopolitan centers as their origin. And almost 30 percent of American export trade passes through its six main ports.

THE LOCATION OF MEGALOPOLIS

Why has this particular portion of the United States developed as it has? Whenever a geographer is asked such a question, the first aspect of the region considered is usually its location. And, indeed, in the case of Megalopolis, the site and the situation of this vast urban region hold clues to its origins and growth.

Many of the site characteristics are visible in the region's outline. Occupying a coastal position, the eastern margin of Megalopolis is deeply convoluted. Peninsulas jut into the Atlantic Ocean. Islands are scattered along the coast, some large enough to support communities. Bays and river estuaries penetrate the landmass in a kind of mirror image of the land's penetration of the ocean. This interpenetrated coastline brings more land area close to the ocean and, in this way, provides greater opportunity for access to cheap water transportation than would a straighter coast.

Quality harbors must also be present, and Megalopolis straddles some of the best natural harbors in America. The northern half of Megalopolis was covered by ice during the most recent of the continental glaciers. As the ice cover began to melt, large river spillways were formed. The erosive power of the rivers cut deeply into the flat coastal plain. As sea level rose, the lower river valleys were "drowned" to form estuaries, and the ocean margin was shifted toward the land's interior. These glacial river valleys formed some of the harbors that later proved useful in the development of Megalopolis.

The other major contribution of the glacial period is more specific to one or two locations. The large amounts of soil, stone, and other debris scraped up by the expanding glaciers were deposited as moraines when the ice front retreated. One series of ridges was left by retreating glaciers just south of what is now the coast of Connecticut. These moraines developed as an island when the seas rose, and it was widened by deposition from the ocean. The island was not made so wide, however, that it could be called anything except Long Island.

Long Island has enhanced the quality of New York's harbor in two major ways. First, the length of coastline available for port facilities, already significant along the Hudson River, is increased considerably. Second, when an urban area grows around a large, fully developed harbor, the growth creates a demand for more space. Good land to accommodate the New York area's urban growth was restricted to the west of the Hudson River in New Jersey by tidal marshes and the erosion-resistant ridge of the Palisades. To the east of the Hudson lies only a narrow finger of land, Manhattan Island. But beyond the East River is Long Island, a flat to slightly rolling land without the barrier marshes of New Jersey. New York's boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens developed early at the western tip of Long Island, and the island offered a great deal of room for further urban expansion toward the east.

Although Megalopolis possesses many high-quality harbors, there are few other site characteristics that contributed so positively to the region's urban economic development. The climate is not exceptionally mild, although the summers are generally of sufficient length and wetness to support farming. Soils are variable, with the soils inland from Baltimore, Maryland, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, better than most found closer to New York.

The general topographic features of Megalopolis south of New York do provide additional urban site benefits. Traveling inland from the Atlantic Coast, a very flat coastal plain is succeeded by a rolling, frequently hilly landscape called the Piedmont. The irregularly rolling relief of the Piedmont is underlain by very old, very hard rocks. This surface is resistant to erosion, and the level of the Piedmont is maintained above that of the coastal plain. Wherever rivers flow off the Piedmont, therefore, a series of rapids and small waterfalls are formed along a line tracing the physiographic boundary – a boundary known as the fall line.

Early settlers found the fall line to be a hindrance to water navigation but an obvious source of water power. Settlements developed along the fall line, locations as far inland as possible but still possessing access to ocean shipping. In addition, because the fall line was often the head of navigation, goods brought inland or those to be exported had to be unloaded at fall line locations for transfer to another mode of transport. These sites also benefited from goods moving for export from the interior to the head of river navigation. In many cases, manufacturing processes could be applied here as well.

This portion of North America was also on or near the most direct sea route between Europe and the productive plantations of the Caribbean colonies and southern America, at least on the homeward voyage. The ports around which Megalopolis later grew, therefore, were convenient stopping places and contributed actively to the transoceanic trade that expanded rapidly during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Also critical to this growth was the location of the core cities relative to the country's interior. Philadelphia and Baltimore grew rapidly because each was the focus of a relatively good-sized and good-quality agricultural region. Access routes to the interior were constructed early and helped support the growth of the trading functions of these cities. Inland from Boston, the soils were (and are) too shallow and rocky and the terrain too rolling for good farming, but the New England hills were covered with hardwood and pine forests nearly ideal for ship construction. Also accessible were the very productive fishing banks off the New England coast and farther south in the rich Chesapeake Bay area.

The importance of accessibility in evaluating a city's situation, however, is most apparent in the case of New York, whose chief advantage lay in its position at the head of the best natural route through the Appalachian Mountains. The Hudson-Mohawk River system, later amplified by the Erie Canal, railroads, and highways, provides access to the Great Lakes to the west, which, in turn, provide access to the broad interior of the country. As settlement density and economic activity on the interior plains increased, large amounts of the goods produced were carried to the urban cores of Megalopolis. The city that benefited most from this growing trade was the one with the greatest natural access to the interior: New York.

During America's colonial period, as trade grew between Europe, the Caribbean area, and the American mainland, small-scale manufacturing began to appear in the larger port cities from Baltimore northward. As urban industry grew, the demand for labor increased, drawing immigrants from northwestern Europe or diverting large numbers of workers from farming, thus swelling the populations of these cities. Banks and other financial institutions underwrote investments in local manufacturing and shipping. Service activities, wholesale and retail businesses, centers of information and control all grew and supported further urban expansion, with the greatest growth occurring in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore.

The most unusual feature of this region is not the fact that these cities grew, but that four such large cities (later to become five with the addition of Washington) continued to grow in close proximity to one another. Washington is unique, of course, because even though it, too, is located on the fall line, its growth has followed directly from expansion of the national government structure. The other four cities, along with many smaller ones along the Megalopolitan axis, depended largely on economic stimulation. So great was national growth during the 19th century, and so strong were the linkages between the interior and these four ports, that none of the four could wholly absorb the flow of goods to any of its neighbors and competitors. By the turn of the 20th century, the combined economic resources of these cities' hinterlands had reached continental proportions.

THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

Throughout Megalopolis, it is the urban forms and urban functions that provide the most significant regional unity to the territory. Tall buildings, busy streets, crowded housing, and industrial plants accompany an array of cultural opportunities – theaters, symphony orchestras, art museums, and large libraries. Also sometimes apparent are deterioration – dilapidated structures, traffic congestion, and air pollution. All of these and more are present in the metropolitan areas of Megalopolis.

These characteristics are also found in most large cities around the world. What distinguishes Megalopolis is that the urban characteristics in this region have spread out so far from their core cities that these urban regions have begun to merge with one another in a process of metropolitan coalescence. Megalopolis became in this way a kind of gigantic laboratory in which intensively urban patterns and peculiarly urban problems could be observed developing at a very large scale.

Population densities in Megalopolis are high, averaging about 305 persons per square kilometer in 1987. Of course, some peripheral counties have populations that are only 10 to 20 percent of the region's overall average density. Settlement density increases as a city is approached, until very high densities are reached near the city core. In New York City, for example, 1987 densities exceeded an average of 226 persons per square hectare, which amounts to more than 22,660 persons per square kilometer.

What other features of city organization are associated with this density pattern? Modern cities result basically from the locational consequences of economic activities. When someone decides to move or to relocate a business into a city, the economic advantages of such a choice fundamentally dominate the decision. So pervasive are these advantages that large numbers of people live close to one another, often closer than they would prefer, and tolerate many negative consequences to participate in the benefits of city organization.

An increasing number of urbanites, however, have minimized some disadvantages of city living by moving their residences to suburban locations. Others have moved even farther, into a zone referred to as exurbia. From small towns, areas of converted vacation homes, and rural estates, exurban commuters travel to distant workplaces. But this spread of population has not eliminated the disadvantages of clustering, only shifted the population facing them. It has also spread the workplaces for those living in the region; a smaller proportion of a sprawling metropolitan population than previously still finds it necessary to enter the central city for work.

A key component of the urban landscape is interaction. In general, the cost of moving something is directly proportional to the distance it must be moved. Activities therefore cluster in cities so that movement costs are minimized. The importance of the ability to move from one place to another in urban regions is evident from the high proportion of urban land devoted to facilitating interaction. The lines of interaction for human movement are visible in streets, subways, bridges, tunnels, sidewalks, and parking lots. In older cities such as those in Megalopolis, the downtowns were laid out when travel was by foot and horse-drawn carriage; therefore, these cities have only about 35 percent of their total central areas devoted to landscape features that support human interaction. In newer cities, developed largely after the rise of the automobile, the proportion is much higher.

Other forms of interaction may be equally important but less visible. The easy movement of information and ideas is supported in cities by the intensively developed telephone, telegraph, teletype, and other communications systems. Ninety years ago, the central business districts of all large cities were crowded with spiderweb networks of telephone lines, testifying to the intensity of communication demands; today, telephone lines are wound into cables and placed underground.

Perhaps the prime motivation for interaction is the geographic separation of supply and demand. Economically, if an item or service is needed at a location that cannot meet that need, the good or service must be obtained at another location. Interaction may occur as a result.

The implications of all this for city landscapes should be clear. There are a great many different kinds of activities in a relatively small area. Some functions tend to cluster together, while others are scattered across the urban region. Since a variety of activities are carried on in a city, interaction is stimulated between functions or within zones of the same function. When the activities are mapped, the result is a greatly mixed pattern of land use.

The concentration of population and urban activities requires supporting functions as well. Traditionally organized and operated as various branches of city government, these public service functions are only indirectly productive in an economic sense, but they are necessary for commerce and industry.

In addition to such services as water, electricity, and sewage and garbage collection, cities provide police and fire protection, construction and maintenance of public movement facilities, health care, documentation of vital population statistics, and educational facilities, among others.

So pervasive did these services become in large cities that immense governmental structures developed to administer them. In the New York metropolitan region, to take the extreme case, more than 1,550 administrative agencies were in operation in 1982.

Yet another major component of the urban landscape is its level of accessibility. Easy access between most sections of an urban area has not always been a dominant consideration in city organization and structure. The original street plans of most cities in Megalopolis, for example, followed the simple square or rectangular grid pattern popular in the 17th and 18th centuries.

As these cities grew, the inadequate access provided by this street system became apparent. A square grid, for example, possesses frequent, right-angle intersections. Because the traffic flow is interrupted at each intersection, a greater traffic volume leads to longer pauses at each intersection. By 1900, Baltimore and Boston had each exceeded populations of 500,000, Philadelphia had reached nearly 1.3 million, and New York was approaching 3.5 million. The main impact of the automobile was then still in the future, but serious congestion was already present in these cities' centers.

Beginning in the 1950s, changes occurred that led to the rapid areal expansion of cities and the increased use of automobiles for travel. An increasing proportion of the work force in the cities began to live at distances and in residential densities that made it uneconomical for mass transit to reach them. Economically, the speed and flexibility of truck transport accelerated the diversion of short-haul freight from rail to road carriers. Traffic planners responded by recommending construction of peripheral circumferential, or ring, highways and high-volume, limited-access expressways to separate local movement from cross-town and through traffic. Partly successful, these changes, plus others, also increased demand for access within the city center, between the center and the periphery, and eventually between sections of the periphery. The entire pattern of accessibility became more complex and difficult to manage.

All of this accentuates another component of the urban landscape. This is a landscape of change. Tens of thousands of new residents enter a large city like Philadelphia or New York each year. Even greater numbers have been leaving, some to distant cities and some only into the metropolitan fringes. Structures are destroyed, new ones built. Street patterns are altered, the pattern of functions is changed, and flows of people, goods, and ideas are shifted to fit these new patterns.

Such changes may be observed in any major region in America, but, in some ways, they actually created Megalopolis.

CHANGING PATTERNS IN MEGALOPOLIS

Perhaps the most fundamental and far-reaching change in Megalopolis during the last 40 years has been the great areal expansion of major metropolitan areas. Greater New York clearly has extended its population the farthest, but the Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington areas have also grown greatly. New York had both the largest initial population and the most intensive economic concentration, but the other three port cities possessed firm foundations for growth as well. At the same time, the federal government rapidly expanded its operations. The District of Columbia (Washington and the District of Columbia are coextensive) was no longer large enough to absorb the burgeoning civil service population and the growing number of people needed to feed, clothe, and otherwise serve them. Urban development spilled into the neighboring states of Virginia and Maryland.

The spread of urban population far beyond city limits also had a strong impact on rural activities in Megalopolis. As city populations grew, a greater number of people had to be fed by foodstuffs shipped in from rural areas. The tens of millions of people in urban Megalopolis consume agricultural products from across America and beyond. Many of those farming the agricultural land close to the cities, however, chose to specialize in higher-priced foods and in products with high perishability. Dairy products, tomatoes, lettuce, apples, and a variety of other intensively produced "table crops" came to dominate farm production in sections of rural Megalopolis.

Also, as land on the margins of urban areas was approached by dense settlement and intense economic activity, the price of land was driven up. A 60-hectare farm purchased decades ago for $20,000 as agricultural land might eventually be sold to a real estate developer for $1 million. The developer, in turn, might subdivide the land into 250 home lots of 0.2 hectares each and then, after putting in utilities and streets, sell each lot for $25,000, or a total $6.25 million.

Even if a farm family could resist the profitability of such a sale, the taxes on the land rose sharply toward urban levels as nearby areas begin to be used for urban activities. Until land use controls were put in place to keep land in agriculture, the only way for a family to remain in farming was to pursue intensive agricultural production devoted to high-value products.

Urban sprawl and the corresponding shifts in agricultural practices in Megalopolis were pulled along the main lines of interurban access between the major urban nodes. Strong flows of traffic developed early between the cities of Megalopolis. When people who continued to work within the major cities relocated their residences, it was only natural that a high proportion chose sites that allowed them easy access to the main cluster of workplaces. The arterial highways and, to a lesser extent, the interurban railroads and main feeder roads became the seams along which metropolitan populations spread first and farthest. As a consequence, the urbanized areas merged first along these main interurban connections. And the demand for increased accessibility generated the construction of even better interurban movement facilities.

As the populations of the separate urban areas grew, the composition of the populations also changed. Prior to 1910, the cities of Megalopolis absorbed large numbers of immigrants from Europe. These migrants passed through one or another of the large Megalopolitan ports, usually New York. Those who did not continue westward into the farming areas or urban centers of the Midwest and Great Plains settled in dense clusters within Megalopolis's cities, usually forming communities of each nationality.

When World War I broke out in Europe, the flow of emigrants stopped, and a new set of migration flows began to filter into Megalopolis. What had been a slow trickle of black migration from southern states began to grow. Black migrants and groups of rural whites from the region repeated the patterns of settlement used by migrant groups from Europe. Most blacks settled within the cities in areas that were already occupied by small black populations.

As the black migration continued through mid-century, population densities increased and generated outward expansion from the original core areas. Often, after many decades of population increase within a city, black densities began to increase in outlying regions of black settlement as well.

Two entirely new aspects of urban change appeared during recent years – a change that may be national in scope but is most dramatic in the largest and oldest cities such as Megalopolis's ports.

First, during the late 1960s, for the first time in U.S. history, people began to leave the largest metropolitan regions – considering both central city and suburbs together – in greater numbers than those who moved in. Smaller cities and towns and the rural areas between them in general have been the primary recipients of these population shifts.

Second, there has been an eruption of high-rise office clusters at various locations in metropolitan areas. The appearance of new metal and glass office skyscrapers has transformed the downtown skyline of many American cities since the mid-1970s. But this feature is no longer limited to the old city cores. Massive office clusters have emerged within the suburban rings surrounding the central cities – many exceeding the square footage of office space of a major city downtown. This change is one that appears to affect most significantly the location of jobs and the pattern of travel to them, rather than the location of residences.

Clearly, urban areas are landscapes of change, and the changes in Megalopolis suit the unusual character of the region. The changes there have been continuous, they have been drastic, and they have occurred on a scale unmatched anywhere else in the world.

[Stephen S. Birdsall is dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Michigan State University and is the co-author of four books and atlases, including Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada.]

[John Florin is chair of the geography department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a master's and a doctoral degree in geography from Pennsylvania State University. His recent publications include Atlas of American Agriculture: The American Cornucopia with Richard Pillsbury and Regional Landscapes of the United States and Canada with Stephen S. Birdsall.]