国務省出版物

米国の歴史の概要 – 成長と変容

2つの大戦争、すなわち南北戦争と第1次世界大戦との間に、アメリカ合衆国は成熟期に達した。50年にも及ばない期間に、米国は、農業を基盤とする共和国から、都市を中心とする国家に変容した。米国のフロンティアは消失した。大規模な工場や製鉄所、大陸横断鉄道、繁栄する都市、そして大規模な農業事業が、各地に出現した。こうした経済成長と富の拡大とともに、さまざまな問題が発生した。全米各地で、少数の企業が、単独で、あるいは相互に提携して、各種の産業全体を牛耳るようになった。労働条件はたいてい劣悪だった。都市があまりに急速に成長したため、住宅の供給や統治の制度が、人口の急増に追い付かなかった。

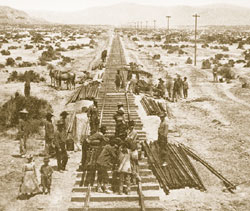

大陸横断鉄道の建設 (1868年) (California State Railroad Museum Library)

ある作家は、「南北戦争は、この国の歴史に深い傷口を開き、それまでの20~30年間に始まりつつあった各種の変革を、一気に表面化させた・・・」と述べている。軍需により、製造業は大いに活気づき、鉄、蒸気、および電力の利用を基盤とする経済プロセスが加速され、また科学と発明が前進した。1860年までの特許許可数は3万6000件であったが、その後の30年間には44万件が許可された。そして、20世紀の第1四半期には、これが100万件近くに達した。

1844年には、すでに、サミュエル・F・B・モールスが電信技術を完成させており、その後間もなく、大陸の遠く離れた各地が、電柱と電線のネットワークで結ばれるようになった。1876年には、アレグザンダー・グラハム・ベルが、電話機を発表した。そして半世紀以内に、全米で1600万台の電話機が普及し、国民の社会的・経済的生活を迅速化した。1867年のタイプライターの発明、1888年の計算機の発明、そして1897年のキャッシュレジスターの発明によって、企業の成長がスピードアップされた。1886年に発明されたライノタイプ植字機と、輪転機、および紙折機によって、8ページの新聞24万部を1時間で印刷することができるようになった。トーマス・エジソンが発明した白熱灯は、何百万もの住宅を照らすようになった。エジソンは、話す機械、すなわち蓄音機を完成させたほか、ジョージ・イーストマンと協力して、映画の開発にも貢献した。これらをはじめとする多くの科学と発明の応用によって、ほとんどすべての分野で生産性が新たな水準に達した。

同時に、米国の基礎産業である製鉄・製鋼業も、高い関税に保護されて成長した。地質学者が新たな鉱床を発見するに伴い、製鉄業は西へ広がっていった。中でもスペリオル湖の湖頭にあるメサビ山地は、世界有数の鉄の産地となった。メサビの鉱床は、採鉱が容易で費用がかからず、採れる鉄は化学的不純物が著しく少なかったため、それまでに比べておよそ10分の1の費用で、非常に優れた品質の鋼鉄に加工することができた。

アンドリュー・カーネギーは、製鋼業の飛躍的発展に非常に大きな役割を果たした。カーネギーは、12歳のときにスコットランドから米国に移住し、紡績工場の糸巻き工から電信局の職員へ、そしてペンシルベニア鉄道会社の社員へと出世していった。そして30歳前には、先見の明に富んだ賢明な投資を始めており、1865年までには、主に鉄に投資をしていた。数年以内に、彼は鉄橋、鉄道、および機関車を製造する各種企業を設立するか、またはそうした企業の株式を保有していた。10年後に、カーネギーは、ペンシルベニア州のモノンガヒーラ川の河畔に全米最大の製鋼所を建設した。 彼は、新しい製鋼所だけでなく、コークスや石炭、スペリオル湖の鉄鉱床、五大湖における蒸気船の船隊、エリー湖の港町、そして連絡鉄道の管理権をも取得した。カーネギーの事業は、他の十数社と手を結び、鉄道会社や船舶会社から有利な条件を勝ち取った。こうした産業発展は、それまでの米国では見られないものであった。

カーネギーは長年にわたって製鉄業を支配したが、製鋼に関連する天然資源、輸送、および工場の完全な独占を実現することはなかった。1890年代には、優位に立つカーネギーに挑戦する新しい企業がいくつか出てきた。彼は、自分の持株会社を新たな法人と合併させ、この法人が米国における最も重要な鉄・鋼鉄資産の大半を保有することになる。

1901年にこの合併から誕生したユナイテッド・ステーツ・スチール・コーポレーション(USスチール社)は、それまでの30年間に進行しつつあった状況を体現したものであった。すなわち、複数の独立した産業事業体を統合あるいは集中化する動きである。南北戦争中に始まったこの傾向は、1870年代を経て、実業家たちが生産過剰による価格の低下と利益の減少を恐れるようになるにつれて勢いを増してきた。彼らは、生産と市場の両方を支配することができれば、競合する複数の企業をひとつの組織にまとめることができる、と気付いた。そのために作られたのが「法人」と「トラスト」である。

法人は、大規模な資本の備蓄を可能にし、事業体に存立の永続性と支配の継続性を与えるもので、投資家にとっては、予想される利益と、事業が失敗した際の有限責任が魅力となった。トラストは、事実上、複数の法人を組み合わせたもので、各法人の株主が、株式を受託者に委託した。(法人を統合する手段としての「トラスト」は、間もなく持株会社に変わったが、トラストという呼び名は残った。)トラストは、大規模な統合、集中化された支配と運営、そして特許の共同所有を可能にした。資本の増大によって、事業を拡張し、外国事業との競争力を付け、当時組織力を付け始めていた労働組合との交渉を有利に進めることが可能となった。また、鉄道会社から有利な条件を取り付け、政界にも影響力を持つことができた。

ジョン・D・ロックフェラーが創設したスタンダード・オイル・カンパニーは、初期の最も強力な法人のひとつであり、その後急速に、綿実油、鉛、砂糖、タバコ、ゴムなどの分野で、さまざまな法人が増えた。間もなく、積極的な個人の実業家が、独自の産業分野を切り開くようになった。フィリップ・アーマーやガスタバス・スウィフトをはじめとする4大精肉業者が、牛肉のトラストを設立した。サイラス・マコーミックは、刈取機の業界で他に抜きん出た。1904年の調査によると、5000を超えるそれまでの独立事業が、およそ300の産業トラストに統合されていた。

こうした統合の傾向は、他の分野にも拡大し、特に輸送と通信の分野で顕著であった。電信事業を支配していたウェスタン・ユニオン社がベル・テレフォン・システム、そしてさらにはアメリカン・テレフォン・アンド・テレグラフ・カンパニーへと統合されていった。1860年代には、コーネリアス・バンダビルトが、13の鉄道を、ニューヨーク(シティ)とバッファローをつなぐ800キロメートルの1本の鉄道に統合した。その後10年間に、バンダビルトは、イリノイ州シカゴおよびミシガン州デトロイトへの鉄道を買収し、ニューヨーク・セントラル鉄道会社を設立した。間もなく、全米の主な鉄道が幹線網に組織され、一握りの事業家によって支配されるようになった。

こうした新たな産業秩序においては、都市がその神経中枢となり、国家のダイナミックな経済的原動力、すなわち資本の膨大な蓄積、事業、金融機関、鉄道操車場、煙を吐く工場、そして大勢の単純労働者や事務職員が、都市に集中した。村だったところに、田舎から、そして海外からも人が集まり、ほとんど一夜にして村が町になり、町が都市に変身した。1830年には、人口8000人以上の地域社会に住む 米国民は15人に1人であったが、1860年にはほぼ6人に1人となり、さらに1890年には10人に3人となっていた。また1860年には人口が100万人に達する都市はひとつもなかったが、30年後にはニューヨーク(シティ)の人口が150万人、イリノイ州シカゴおよびペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィアの人口がそれぞれ100万人を超えていた。その30年間に、フィラデルフィアおよびメリーランド州ボルティモアでも人口が倍増し、ミズーリ州カンザスシティおよびミシガン州デトロイトの人口は4倍に増え、オハイオ州クリーブランドの人口は6倍、そしてシカゴの人口は10倍に増えた。ミネソタ州ミネアポリスやネブラスカ州オマハのように、南北戦争が始まったころには小さな村であった多くの地域社会では、人口が50倍以上に増えた。

拡張する国家にとって鉄道はとりわけ重要であった。そして鉄道会社の行動はしばしば批判の対象となった。鉄道会社は、大口の荷主に対しては、料金の一部を払い戻すことによって、より安価な輸送料金を提供し、このため小口の荷主は不利であった。また、輸送料金が距離と比例しないことも多かった。通常、数社が競合する路線では料金が抑えられた。1社の鉄道しかない路線では料金が高くなる傾向があった。従って、シカゴからニューヨークまで1280キロメートルの距離を輸送する方が、シカゴから数百キロメートルの町へ輸送するより料金が安かった。さらに、ライバル会社同士が競争を避けるために、事前に計画して輸送の仕事を分割(「プール」)し、収益を共同資金として集めてから分配することもあった。

こうした慣行に対する市民の反感が高まり、各州が規制の努力を始めたが、この問題は国家的な性質を持つものであった。荷主たちは、連邦議会による措置を要求した。1887年に、グローバー・クリーブランド大統領が州際通商法に署名をした。これは、法外な料金、プール、払戻し、そして料金の差別を禁じる法律であった。同法によって、この法律を監督する州際通商委員会(ICC)が設置されたが、委員会には法の執行権限がほとんど与えられなかった。最初の何十年間かは、ICCによる規制および料金引き下げの努力はほぼすべて、合憲性審査を通過することができなかった。

クリーブランド大統領は、外国製品に対する保護関税にも反対した。こうした保護関税は、この時代の政治を支配した歴代の共和党大統領の下では、永続的な国家政策として受け入れられてきた。保守派の民主党員であったクリーブランドは、関税による保護は大企業への不当な補助金であり、トラストに価格決定力を与えることによって一般の米国民を不利な状況に置くものである、と考えた。民主党員は、南部の支持基盤の利害を反映して、保護に反対し「収入のみのための関税」を支持するという南北戦争以前の方針に戻っていた。

1884年に僅差で当選したクリーブランド大統領は、第1期には関税改革を行うことができなかった。彼は、関税改革を再選のための選挙運動の柱としたが、保護主義を支持した共和党候補のベンジャミン・ハリソンが激戦の末当選した。1890年に、ハリソン政権は、その公約を果たし、すでに高かった関税率をさらに引き上げるマッキンリー関税法を成立させた。マッキンリー関税は小売価格の上昇を引き起こしたとされ、不満の声が高まった。これが1890年の選挙における共和党の敗北につながり、1892年の選挙でクリーブランドが再び大統領に当選する道を開いた。

この間に、トラストに対する国民の反感が高まった。1880年代を通じて、米国の巨大企業は、ヘンリー・ジョージやエドワード・ベラミーなどの改革主義者によって激しく攻撃された。1890年に可決されたシャーマン反トラスト法は、州際取引を制限するあらゆる企業連合(カルテル)を禁止し、厳しい罰則を設けた数種類の執行手段を提供した。同法は、漠然とした一般概念を記したものであり、成立直後はほとんど実績を上げることがなかった。しかし、その10年後に、セオドア・ルーズベルト大統領が、この法律を精力的に活用することになる。

工業の大幅な発展にもかかわらず、米国の基盤となる産業は引き続き農業であった。南北戦争後の製造業革命に匹敵する農業革命は、人手による労働から機械農業へ、そして自給自足の農業から商業農業への移行である。1860年から1910年までの間に、米国内の農場数は200万から600万へと3倍に増え、耕作面積は1億6000万ヘクタールから3億5200万ヘクタールへ、2倍以上に増えた。

1860年から1890年までの間に、小麦、トウモロコシ、綿花といった主要農作物の生産高は、米国におけるそれまでの記録をすべて上回った。同期間に、米国の人口は2倍以上に増え、中でも都市部における成長率が最も高かった。しかし、米国の農民は、米国の労働者とその家族が消費する量以上の穀物、綿花、牛肉、豚肉、綿花を生産したため、余剰農産物が増え続けた。

この優れた業績の要因はいくつかあった。そのひとつは西部への拡張であり、もうひとつは技術革命であった。1800年に、 鎌を使って手で小麦を刈り入れていた農民は、1日にせいぜい5分の1ヘクタールしか刈り取ることができなかった。しかしその30年後には、クレードル(枠付きの大鎌)を使って1日に5分の4ヘクタールを刈り取ることが可能となった。1840年には、サイラス・マコーミックが、10年近くをかけて開発した刈取機で、1日に2~2.5ヘクタールを刈り取るという奇跡を成し遂げた。彼は、西の平原の新興都市シカゴへ移住して工場を開設し、1860年までには刈取機25万台を販売した。

このほかにも、自動ワイヤバインダー、脱穀機、そして刈取機と脱穀機を組み合わせたコンバインなどの農業機械が次々と開発された。さらにプランター、カッター、ハスカー、シェラーなどの機械が登場し、クリーム分離器、肥料散布機、ポテト・プランター、牧草乾燥機、孵卵器、など多くの機械が発明された。

農業革命において、機械とほぼ同等の重要性を持ったのは、科学であった。1862年のモリル・ランドグラント・カレッジ法によって、農業・産業大学を設立するために連邦所有の公有地が各州に供与された。これらの大学の目的は、教育機関ならびに科学的農業の研究センターとしての役割を果たすことであった。その後連邦議会が、全米各地に農業試験場を設置するための予算を確保し、直接農務省に研究目的の資金を提供した。新世紀に入るころには、全国の科学者がさまざまな農業研究プロジェクトに携わっていた。

そうした科学者の1人、マーク・カールトンは、農務省によってロシアへ派遣された。彼はロシアで、さび菌と干ばつに強い秋まき小麦を発見し、母国に持ち帰った。この小麦は現在、米国で収穫される小麦の半分以上を占めている。また、マリオン・ドーセットは、恐れられていた豚コレラを克服し、ジョージ・モーラーは、口蹄病の防止に貢献した。ある研究者は、北アフリカからカヒアモロコシを持ち帰った。また黄花アルファルファも輸入された。カリフォルニア州のルーサー・バーバンクは、何十もの果物や野菜の新種を作った。ウィスコンシン州では、スティーブン・バブコックが、牛乳の乳脂肪含有量を測定する試験法を開発した。アラバマ州のタスキーギ大学では、アフリカ系米国人の科学者ジョージ・ワシントン・カーバーが、ピーナッツ、サツマイモ、および大豆の新たな使用法を何百も開発した。

農業科学・技術の急発展は、程度の差こそあれ世界中の農民に影響を及ぼした。収穫高が増加し、小規模な生産者は閉め出され、工業都市への人口流入に拍車がかかった。さらに、鉄道や蒸気船が、各地の市場を、単一の巨大な世界市場に結び付けるようになり、地上線や大西洋を横断するケーブルによって瞬時に価格が通信されるようになった。農産物価格の低下は、都市部の消費者にとっては朗報であったが、米国の多くの農民は生活を脅かされ、農民の間に不満の波が広がっていった。

再建期後、南部の指導者は工業誘致に力を入れた。各州は、多大な奨励策と安価な労働力を投資家に提供し、鉄鋼、木材、タバコ、および繊維などの産業を育成した。しかし、1900年における南部の工業が全米の工業基盤に占める割合は、1860年当時とほぼ同じであった。また、こうした工業化推進の代償は大きかった。南部の工場町では、疾病がまん延し、児童就労が急増した。南北戦争から30年たって、南部はまだ貧しく、ほとんどが農村地帯であり、経済的には他地域に依存していた。そして、南部における人種関係は、単に奴隷制の遺産を反映していただけでなく、いかなる代償を払おうとも白人至上主義を強行しようとする決意が、南部の歴史の中心的なテーマとして浮上しつつあった。

妥協を拒否する南部の白人たちは、白人の優勢を維持するために州による支配を確立する手段を見つけた。また、国家と州の権力の適切な均衡に対する伝統的な南部の見解を支持する最高裁判決がいくつか出されたことによって、こうした白人たちの活動がますます強化された。

1873年に最高裁は、合衆国憲法修正第14条(市民の権利に対する制限の禁止)は、アフリカ系米国人を州の権限から保護するための新たな特権または免除を与えるものではない、との判決を下した。さらに最高裁は1883年に、修正第14条は、州ではなく個人が差別を行うことを妨げるものではない、と判決した。また「プレッシー対ファーガソン」事件(1896年)で最高裁は、鉄道やレストランなどの公的施設における、アフリカ系米国人に対する「分離すれども平等」の方針は、彼らの権利を侵害するものではない、と判断した。間もなく、人種による分離の原則は、鉄道からレストラン、ホテル、病院、そして学校まで南部の生活のあらゆる部分に拡大された。また、法律によって分離されない部分は、一般的慣行によって分離された。続いて、投票権がさらに制限された。暴徒によるリンチの断続的発生は、アフリカ系米国人を隷属させようとする南部の強い決意を浮き彫りにした。

広がる差別に直面して、多くのアフリカ系米国人は、適度の経済目標を目指し、一時的な社会的差別を受け入れる、というブッカー・T・ワシントンの方針に従った。一方、アフリカ系米国人の知識人W・E・B・デュボイスを筆頭に、政治行動によって人種隔離に挑戦しようとする人々もいた。しかし、2大政党がいずれもこの問題に関心を示さず、当時は科学的な理論として黒人の劣等性が一般に受け入れられていたため、人種的公正を要求する声はほとんど支持を得られなかった。

1865年には、米国のフロンティアは、ミシシッピ川沿いの各州の西の境界にほぼ沿っていたが、テキサス、カンザス、およびネブラスカの東部が西へ突出していた。 その先には、南北に1600キロメートル近くにわたって巨大な山脈が伸びており、そこには金、銀、その他の鉱床が豊富にあった。さらに西には、太平洋沿岸の森林地帯まで、平原と砂漠が広がっていた。カリフォルニアの入植地と、点在する前哨地を除けば、広大な内陸地域にはアメリカ先住民が住んでいた。その中には、スー、ブラックフット、ポーニー、シャイアンなどの大平原の諸部族や、アパッチ、ナバホ、ホピなど南西部の諸部族がいた。

それからわずか四半世紀の後には、米国のほぼ全土が州または準州となっていた。山岳地帯の至る所に鉱山労働者らが入り、地中を掘り進み、ネバダ、モンタナ、およびコロラドに小さな地域社会を設立していった。蓄牛の牧場主らは、広大な草原を利用し、テキサスからミズーリ川上流に及ぶ巨大な土地の所有権を主張した。牧羊者たちは、谷間や山の斜面を利用した。農民は、平原を耕し、東部と西部の間隙を埋めていった。1890年までには、米国のフロンティアは消失していた。

1862年の自営農民法では、64ヘクタールの土地区画に住み、その土地を改良する者には、その64ヘクタールの土地を無償で与えることが定められ、これにより入植が促進された。しかし、こうして土地を得た人々には不運なことに、大平原地域のほとんどは農業より牧畜に適しており、1880年までには、2240万ヘクタール近い「無償」の土地が、牧畜業者または鉄道会社の手に渡っていた。

また1862年には、連邦議会がユニオン・パシフィック鉄道の建設許可を可決し、同社はアイオワ州カウンシル・ブラフスから西方へ、主に旧兵士やアイルランドからの移民を労働力として、鉄道を建設していった。同時に、セントラル・パシフィック鉄道は、主に中国人移民の労働力に頼って、カリフォルニア州サクラメントから東へ向かう鉄道の建設を始めた。全米の人々が興奮して注目する中で、この2つの鉄道はお互いを目指して着々と前進していき、ついに1869年5月10日、ユタ州プロモントリー・ポイントで結合した。こうして、それまでは何カ月もかかる苦しい道程であった太平洋岸と大西洋岸の間の移動が、およそ6日間の旅に短縮された。その後も大陸横断鉄道が着々と増加し、1884年までには、4本の鉄道幹線が、ミシシッピ川流域中部と太平洋岸を結んでいた。

米国極西部で最初に大量の人口流入があったのは、山岳地帯であった。1848年にカリフォルニア州で金が発見され、その10年後にはコロラド州とネバダ州で、また1860年代にはモンタナ州とワイオミング州で、そして1870年代にはダコタ準州のブラックヒル地域でも金が発見された。鉱山労働者たちが土地を切り開き、コミュニティを作り、より永続的な集落の基盤を築いた。しかしながら、最終的には、採鉱を専門とする地域社会も多少は残ったものの、モンタナ、コロラド、ワイオミング、アイダホ、およびカリフォルニアの各州における真の富は、その草原と土壌にあった。長年にわたりテキサス州の重要な産業となっている牧畜は、南北戦争後に繁栄した。そのころ、起業精神に富んだ人々が、テキサス牛の群れを広大な公有地を通って北へ移動させるようになったのである。牛は牧草を食べながら移動し、カンザス州の鉄道輸送地点に到着するころには、出発時より太って大きくなっていた。こうした牛の移動は毎年の行事となり、北へ向かう道では、何百キロメートルにもわたって点々と牛の姿が見られた。

続いて、コロラド、ワイオミング、カンザス、ネブラスカの各州およびダコタ準州に巨大な牧場が出現し始めた。西部の各都市は、家畜の屠殺と食肉処理の中心地として栄えた。畜産ブームは1880年代半ばにピークを迎えた。そのころには、牧場主たちに続いて、農民が、家族や馬、牛、豚を連れて、幌馬車で移動してきた。彼らは、自営農民法の下で、土地の権利を主張し、新たに発明された鉄条網で土地を囲った。法的な権利を得ずに土地を使っていた牧場主たちは土地を追われた。

牧畜と牛の移動は、米国の神話の中でフロンティア文化の最後の象徴となるカウボーイの存在を生んだ。現実にはカウボーイの生活は非常に厳しかった。ゼイン・グレーのような作家やジョン・ウェインなどの映画俳優によって描かれたカウボーイは、大胆、高潔、かつ行動的な、力強い神話的人物像だった。これに対して反動的な見方が出始めたのは20世紀後半になってからであった。歴史家や映画製作者は、「開拓時代の西部」を、人間性の最良の部分よりむしろ最悪の面が現れがちな人々の住む浅ましい場所として描くようになった。

東部の場合と同様、大平原地帯や山岳地帯へ鉱山労働者、牧場主、そして入植者たちが流入するに従い、西部のアメリカ先住民との対立が増えた。グレートベースンのユート族からアイダホのネスパース族まで、アメリカ先住民の多くの部族が、いずれかの時点で白人と戦った。しかし、フロンティアの前進に対して最も強力な反対勢力となったのは、北部平原地帯のスー族と南西部のアパッチ族であった。レッド・クラウドやクレージー・ホースなど優秀な指導者に率いられたスー族は、特にスピーディな騎乗戦に長けていた。同様にアパッチ族も、本拠地である砂漠や峡谷の環境で巧みに迅速に戦った。

スー国家の一部であるダコタ族が、長年の不満が理由で米国政府に戦争を宣言し、白人入植者5人を殺害した事件の後、平原のインディアンとの紛争が悪化した。南北戦争の期間を通じて、反乱や攻撃が続いた。1876年に、ダコタのゴールドラッシュがブラックヒルズに侵入し、最後の深刻なスー戦争が勃発した。鉱山労働者をスー族の狩猟地に立ち入らせないようにするはずの軍隊は、スー族の土地を守る努力をほとんどしなかった。ところが、条約の権利に従ってこの地域で狩猟をしていたスー族の一団に対して行動を取るように命令を受けると、軍隊は迅速かつ積極的に動いた。

1876年、決着のつかない数度の戦闘の後に、騎兵の小分隊を率いたジョージ・カスター大佐は、リトル・ビッグホーン・リバーで、圧倒的多数のスー族とその同盟の軍隊に遭遇した。この戦いでカスターとその分隊は全滅した。しかし、アメリカ先住民の反乱は間もなく鎮圧された。その後1890年に、サウスダコタ州ウンデッドニーの北部スー族保留地で行われるゴーストダンスの儀式がきっかけとなって反乱が起き、最後の悲劇的な戦いが行われ、スー族の男女・子ども300人近くが死んだ。

しかし、そのはるか以前に、平原地帯のインディアンの生活様式は、白人人口の拡大、鉄道の到来、そしてバッファローの大量殺戮によって、すでに破壊されていた。バッファローは、1870年からの10年間に、入植者による無差別な狩猟によってほとんど絶滅していた。

南西部におけるアパッチ族との戦いは、1886年に、最後の重要な酋長であったジェロニモが捕虜となるまで続いた。

モンロー政権以降、米国政府は、アメリカ先住民を、白人のフロンティアの外へ移動させる政策を取ってきた。しかし、当然のことながら、保留地はますます小さくなり、そうした狭い保留地に多くの人が押し込まれるようになった。国民の一部からは、アメリカ先住民に対する政府の措置に抗議する意見も出てきた。例えば、東部出身で西部に居住したヘレン・ハント・ジャクソンは、著書「A Century of Dishonor」(1881年)で、アメリカ先住民の窮状を浮き彫りにし、米国の良心に訴えた。改革論者の大半が、アメリカ先住民を米国の主流文化に同化させるべきだと考えた。連邦政府は、ペンシルベニア州カーライルに学校を設立し、そこでアメリカ先住民の子どもたちに白人の価値観と信条を押し付けようとした。(米国が生んだ最高の運動選手と広く認められているジム・ソープは、20世紀初めにこの学校で有名になった。)

1887年に、ドーズ法(一般土地割当法)により、米国のアメリカ先住民に対する政策が逆転し、大統領が部族の土地を分割し、各家族の長に65ヘクタールの土地を付与することが認められた。この割当地は、25年間は政府の信託下に置かれ、その後は所有者が全面的な権利と市民権を得た。しかしながら、こうした割り当ての対象とならなかった土地は、入植者に売却された。この政策は、善意に基づいたものであったかもしれないが、実際にはアメリカ先住民の土地をさらに略奪することになり、悲惨な結果をもたらした。また、諸部族の共同体組織を壊すことによって、伝統文化の破壊を加速させた。1934年には、保留地における部族と共同体の生活の保護を目指すインディアン再組織法によって、米国の政策が再び変更された。

19世紀末の何十年間かは、米国にとって帝国主義的拡張の時期であった。しかしながら、ヨーロッパの各帝国と争い、独自の民主的発展を遂げてきた歴史を持つ米国は、ヨーロッパのライバル諸国とは異なる道を歩んだ。

19世紀末における米国の拡張主義にはさまざまな原因があった。国際的には、この時期に帝国主義の熱狂が高まり、ヨーロッパ列強がアフリカで植民地競争を繰り広げ、アジアでは日本と共に影響力と通商を求めて争った。セオドア・ルーズベルト、ヘンリー・カボット・ロッジ、およびエリフ・ルートなどの有力者は、米国がその国益を守るためには、経済的勢力圏をも広げなければならないと考えた。強力な海軍ロビーもこの意見を支持し、国家の経済的・政治的安全保障に不可欠なものとして艦隊の拡張と海外の港湾網の確立を求めた。より広範には、当初米国の大陸における拡張を正当化するために唱えられた「明白な運命(領土拡張政策)」が、米国には西半球およびカリブ諸国そして太平洋の反対側にも米国の影響力と文明を拡張させる権利と義務がある、という主張の根拠として復活した。

同時に、北部の民主党員および改革主義の共和党員から成る多様な反帝国主義派の声も弱まることはなかった。その結果として、米国の帝国拡張は、断片的でどっちつかずのものとなった。植民地主義を志向する政権は、政治的な支配より通商や経済問題に関心を持つことが多かった。

米国による初めての大陸外への拡張は、1867年のロシアからのアラスカ購入であった。当時のアラスカはイヌイット族その他の先住民がまばらに住む土地であり、ほとんどの米国民は、ウィリアム・スワード国務長官の提案によるアラスカ購入に無関心であるか、または憤慨し、アラスカを「スワードの愚行」あるいは「スワードの冷蔵庫」と揶揄する人々もいた。しかし30 年後に、アラスカのクロンダイク川で金が発見されると、何万人もの米国民が北へ向かい、その多くはアラスカに永住した。アラスカは1959年に米国の49番目の州となり、テキサスに代わって米国で最も面積の広い州となった。

1898年のスペイン・アメリカ戦争は、米国の歴史の転換点となった。この戦争により、米国はカリブ海および太平洋の諸島に対して支配権ないし影響力を持つようになった。

かつて新世界において広大な領土を誇ったスペインの帝国は、1890年代に入るころにはキューバとプエルトリコを残すのみとなり、太平洋地域ではフィリピン諸島がスペインの勢力の中核となっていた。この戦争の原因は3つあった。それは、スペインの専制に対するキューバ国民の反感、キューバの独立闘争に対する米国の共感、そして国家主義的でセンセーショナルなマスコミによる刺激もあって生じた新たな国家的自己主張の精神であった。

1895年までには、キューバの反抗が強まり、独立のためのゲリラ戦争となっていた。米国民のほとんどはキューバ国民に同情的であったが、クリーブランド大統領は中立を保つ意志を固めていた。しかしながら、その3年後、ウィリアム・マッキンリー政権の時代に、キューバの反乱に対するスペインの手荒な処理を米国が懸念しているとスペインに伝えるために「儀礼訪問」としてハバナへ派遣された米国の戦艦メーンが港湾内で爆発し、250 人以上が死亡した。これは、おそらく事故による内部爆発であったと思われるが、ほとんどの米国民は、スペインの仕業であると考えた。人々の怒りは、センセーショナルな報道によってさらに煽られ、全米に広がった。マッキンリー大統領は平和を維持しようとしたが、数カ月とたたないうちにその努力が無駄であると考え、軍事介入を勧告した。

スペインとの戦争は、迅速かつ果断に実行された。4カ月にわたる戦争の間に、米国が大きく後退することは1度もなかった。宣戦布告の1週間後に、当時香港に駐屯していた戦艦6隻から成るアジア方面戦隊の司令官ジョージ・デューイ准将がフィリピン諸島へ向かい、マニラ湾に停泊していたスペインの艦隊を全滅させたが、米国側には1人の戦死者も出さなかった。

一方キューバでは、米軍がサンティアゴの近くに上陸し、一連の戦闘に次々と勝利した後、港湾を攻撃した。スペインの装甲巡洋艦4隻がサンティアゴ湾を出て米国海軍と交戦したが敗れ、巨大な残骸と化した。

サンティアゴ陥落の知らせに、ボストンからサンフランシスコまで米国内各地で、人々は警笛を鳴らし、旗を振って祝った。新聞社は、キューバとフィリピンに特派員を送り、彼らは国家の新たな英雄たちの名声を喧伝した。中でも誉れ高かったのがデューイ准将とセオドア・ルーズベルトである。ルーズベルトは、海軍次官補を辞職して、志願兵から成る連隊「ラフ・ライダーズ」を率いてキューバで戦っていた。間もなくスペインは、戦争の終結を求めた。1898年12月10日に締結された和平条約により、キューバは独立に先立って一時的に米国の占領下に置かれた。また、スペインは、戦争賠償金の支払いに代えて、米国にプエルトリコとグアムを譲渡し、フィリピンを2000万ドルで売却した。

公式には、米国の政策は、こうした新しい領地が、民主的な自治へと移行することを奨励したが、これらの領地はいずれもそのような政治制度を体験したことがなかった。実際には、米国は植民地の統治者としての役割を果たすことになった。米国は、プエルトリコとグアムに対しては行政支配を維持し、キューバには名目のみの独立を与え、フィリピンでは、武装独立運動を厳しく弾圧した。(フィリピンは1916年に議会の両院の選挙を行う権利を獲得した。1936年には、おおむね自治的なフィリピン連邦が設立された。第2次大戦後の1946年に、フィリピン諸島はようやく完全な独立を達成した。)

太平洋地域で米国が関与したのはフィリピンだけではなかった。スペイン・アメリカ戦争と同年に、ハワイ諸島との新たな関係も始まった。それ以前のハワイとの接触は、主として宣教師や貿易商によるものであった。しかしながら、1865年以降は、米国の投資家が、サトウキビとパイナップルを中心とするハワイ諸島の資源開発に乗り出した。

1893年にリリ・ウオカラニ女王の政権が外国からの影響を阻止する意図を発表すると、米国の実業家たちはハワイの有力者と協力して、女王を退位させた。ハワイの新政府は、在ハワイ米国大使とハワイに駐留する米軍の支援を得て、米国への併合を求めた。2期目に入ったばかりのクリーブランド大統領は、ハワイ併合を拒否し、ハワイを名目上独立したままとしたが、スペイン・アメリカ戦争が始まると、連邦議会はマッキンリー大統領の支持を得て、併合条約を批准した。ハワイは1959 年に50番目の州となった。

米国の拡張の理由のひとつは、ある程度、経済的利益にあり、特にハワイではそうであったが、ルーズベルト、ヘンリー・カボット・ロッジ上院議員、およびジョン・ヘイ国務長官などの有力な政策策定者、そしてアルフレッド・セイヤー・マハン海軍大将などの有力な戦略家にとって、主な動機は戦略地政学的なものであった。彼らにとっては、ハワイ獲得による最大の配当は真珠湾であり、これが後に太平洋中央部における主要な米国海軍基地となった。フィリピンとグアムは、ウェーク島、ミッドウェー、および米領サモアといった太平洋の基地を補完した。プエルトリコは、米国が中米における運河建設を検討するに伴い重要性を増しつつあったカリブ海地域における重要な足場であった。

米国の植民地政策は、民主的な自治政府を目指す傾向があった。フィリピンの場合と同様に、連邦議会は1917年に、プエルトリコの住民に、プエルトリコの全議員を選挙で選ぶ権利を与えた。また、この法律により、プエルトリコが正式に米国の準州となり、住民に米国市民権が与えられた。1950年には、連邦議会がプエルトリコに自らの将来を決定する完全な自由を与えた。1952年に、プエルトリコの住民は、正式な州となることも、完全に独立することも拒否し、自由連合州という地位を選んだ。これは、強力な分離独立運動にもかかわらず、現在も継続している。プエルトリコの住民は、自由に米国本土へ出入りすることができ、他の米国市民と全く同様の政治的・市民的権利を与えられており、大勢のプエルトリコ人が米国に定住している。

スペインとの戦争によって、パナマ地峡を横断する運河を築いて2つの大洋をつなぐという構想への関心が復活した。世界の主な商業国家は、そのような運河が海洋貿易にとって有用であることを長年にわたって認識していた。フランスが19世紀末にそのような運河の掘削を始めたが、技術的な困難を克服することができなかった。カリブ海と太平洋で勢力を持つようになった米国は、このような運河が、経済的な利益をもたらすとともに、2つの大洋間の戦艦の移動を迅速化すると考えた。

20世紀が始まるころ、現在のパナマは、コロンビア北部の1州であり、国家に対して反抗していた。1903年にコロンビア議会が、米国に運河の建設と運営の権利を与える条約の批准を拒否すると、業を煮やしたパナマ住民の一団が、米国海兵隊の支援を得て反乱を起こし、パナマの独立を宣言した。こうして分離した国家は、直ちにセオドア・ルーズベルト大統領によって承認された。同年11月に調印された条約の下で、パナマは米国に、大西洋と太平洋を結ぶ幅16キロメートルの土地(パナマ運河地域)の永久租借権を与え、米国は一時金1000万ドルと年間25万ドルの使用料を支払うことになった。後にコロンビアに一部補償金として2500万ドルが支払われた。75年後に、パナマと米国は新たな条約の交渉を行った。この条約により、1999年12月31日をもってパナマ運河地域の主権はパナマに移り、運河はパナマに譲渡されることが定められた。

1914年にジョージ・W・ゲーソルズ大佐の指揮の下で完成したパナマ運河は、工学の大きな勝利であった。また、マラリアと黄熱病が同時に克服されたことが運河の完成に貢献し、20世紀における予防医学の偉業のひとつとなった。

米国は、中南米各地で断続的な介入を行うというパターンに陥った。1900年から1920年までの間に、米国は、ハイチ、ドミニカ共和国、ニカラグアをはじめとする西半球6カ国に対して持続的に介入した。こうした介入を正当化する理由として、米国は、政治の安定と民主主義政府の確立、米国に有利な投資環境の整備(これはドル外交と呼ばれた)、パナマ運河への海上交通路の確保、さらにはヨーロッパ諸国による強制的な債権回収の阻止といった要因を挙げた。1867年に米国は、フランスに圧力をかけてメキシコからフランスの軍隊を引き上げさせた。しかしその半世紀後には、ウッドロー・ウィルソン大統領が、メキシコ革命に影響を及ぼすことと、米国の領土への侵入を防ぐことを目的とする作戦の一部として、逃亡していた無法者フランシスコ・「パンチョ」・ビリャを捕えるために米軍兵士1万1000人をメキシコ北部に派遣したが、この作戦は失敗に終わった。

また米国は、西半球における最も強力な、そして最も自由な国家として、米州諸国の協力の制度的基盤を確立する努力をした。1889年に、ジェームズ・G・ブレーン国務長官は、西半球の独立国家21カ国が、紛争の平和的解決とより緊密な経済的結び付きを追求する共同組織を結成することを提案した。その結果として、1890年に汎米連合が設立された。これが今日の米州機構(OAS)である。

その後、ハーバート・フーバー(1929~33年)およびフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト(1933~45年)の両政権は、米国が中南米に介入する権利を認めなかった。特に、1930年代のルーズベルト大統領の善隣政策は、米国と中南米の間の緊張をすべて解消するものではなかったが、米国による過去の介入や一方的な行動に対する敵意の多くを消散させることに貢献した。

世紀の変わり目に、フィリピンで新たな地歩を固め、ハワイではすでに確固たる基盤を築いていた米国は、中国との活発な貿易に大きな期待を寄せていた。しかしながら、中国では、すでに日本とヨーロッパ諸国が、海軍基地、租借地、独占通商権、そして鉄道建設・採鉱への独占投資権といった形で、広く勢力圏を築いていた。

米国の外交政策には、極東でヨーロッパの帝国列強と競争したいという願望と並んで、理想主義が存在していた。従って米国は、主義の問題として、すべての国家に平等な通商特権が与えられることを求めた。1899年9月、ジョン・ヘイ国務長官は、すべての国家に対する中国の「門戸開放」を主張した。これは、ヨーロッパ諸国が支配していた地域における通商機会の平等化(関税、港湾税、および鉄道料金の均等化など)を求めるものであった。この門戸開放政策は、内容は理想主義的なものであったが、実質的には、公然たる植民地主義の実行という汚名を回避しながら、植民地主義の利点を追求しようとする外交戦略であり、一応の成果を収めた。

1900年に中国は、義和団の乱によって、外国の勢力に対する反乱を起こした。同年6月、反乱軍が北京を占拠し、市内の外国公館を攻撃した。ヘイ国務長官は直ちに、ヨーロッパ列強と日本に対して、米国は中国の領土権および行政権のいかなる侵害にも反対することを公表し、改めて門戸開放政策を宣言した。反乱の鎮圧後、ヘイは、過酷な賠償金の重圧から中国を守った。英国、ドイツ、およびその他の植民地勢力は、主として米国の善意に応えて、門戸開放政策と中国の独立を公に認めた。しかし実際には、彼らは中国における特権的な地位を確固たるものとした。

その数年後、セオドア・ルーズベルト大統領は、行き詰まっていた日露戦争(1904~05年)の仲裁役を果たした。この戦争は、さまざまな面で、中国北部の満州における支配権と影響力をめぐる闘争であった。ルーズベルトは、この和解によって、米国の事業に対する門戸開放の機会が得られることを期待したが、旧敵同士の日本とロシアおよび他の帝国列強は、米国を締め出すことに成功した。他の地域と同様、ここでも、米国は経済帝国主義のために軍隊を派遣する意志はなかった。少なくとも、ルーズベルト大統領は、1906年のノーベル平和賞受賞という満足を得ることができた。日本はこれによって利益を得たにもかかわらず、この誇り高く、新たに自己主張するようになった島国と、米国とは、20世紀前半の数十年間にわたり、断続的に困難な関係に陥ることになった。

|

Growth and Transformation

“Upon the sacredness of property, civilization itself depends.”

-- Industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, 1889

Between two great wars – the Civil War and the First World War – the United States of America came of age. In a period of less than 50 years it was transformed from a rural republic to an urban nation. The frontier vanished. Great factories and steel mills, transcontinental railroad lines, flourishing cities, and vast agricultural holdings marked the land. With this economic growth and affluence came corresponding problems. Nationwide, a few businesses came to dominate whole industries, either independently or in combination with others. Working conditions were often poor. Cities grew so quickly they could not properly house or govern their growing populations.

TECHNOLOGY AND CHANGE

“The Civil War,” says one writer, “cut a wide gash through the history of the country; it dramatized in a stroke the changes that had begun to take place during the preceding 20 or 30 years. ...” War needs had enormously stimulated manufacturing, speeding an economic process based on the exploitation of iron, steam, and electric power, as well as the forward march of science and invention. In the years before 1860, 36,000 patents were granted; in the next 30 years, 440,000 patents were issued, and in the first quarter of the 20th century, the number reached nearly a million.

As early as 1844, Samuel F. B. Morse had perfected electrical telegraphy; soon afterward distant parts of the continent were linked by a network of poles and wires. In 1876 Alexander Graham Bell exhibited a telephone instrument; within half a century, 16 million telephones would quicken the social and economic life of the nation. The growth of business was speeded by the invention of the typewriter in 1867, the adding machine in 1888, and the cash register in 1897. The linotype composing machine, invented in 1886, and rotary press and paper-folding machinery made it possible to print 240,000 eight-page newspapers in an hour. Thomas Edison’s incandescent lamp eventually lit millions of homes. The talking machine, or phonograph, was perfected by Edison, who, in conjunction with George Eastman, also helped develop the motion picture. These and many other applications of science and ingenuity resulted in a new level of productivity in almost every field.

Concurrently, the nation’s basic industry – iron and steel – forged ahead, protected by a high tariff. The iron industry moved westward as geologists discovered new ore deposits, notably the great Mesabi range at the head of Lake Superior, which became one of the largest producers in the world. Easy and cheap to mine, remarkably free of chemical impurities, Mesabi ore could be processed into steel of superior quality at about one‑tenth the previously prevailing cost.

CARNEGIE AND THE ERA OF STEEL

Andrew Carnegie was largely responsible for the great advances in steel production. Carnegie, who came to America from Scotland as a child of 12, progressed from bobbin boy in a cotton factory to a job in a telegraph office, then to one on the Pennsylvania Railroad. Before he was 30 years old he had made shrewd and farsighted investments, which by 1865 were concentrated in iron. Within a few years, he had organized or had stock in companies making iron bridges, rails, and locomotives. Ten years later, he built the nation’s largest steel mill on the Monongahela River in Pennsylvania. He acquired control not only of new mills, but also of coke and coal properties, iron ore from Lake Superior, a fleet of steamers on the Great Lakes, a port town on Lake Erie, and a connecting railroad. His business, allied with a dozen others, commanded favorable terms from railroads and shipping lines. Nothing comparable in industrial growth had ever been seen in America before.

Though Carnegie long dominated the industry, he never achieved a complete monopoly over the natural resources, transportation, and industrial plants involved in the making of steel. In the 1890s, new companies challenged his preeminence. He would be persuaded to merge his holdings into a new corporation that would embrace most of the important iron and steel properties in the nation.

CORPORATIONS AND CITIES

The United States Steel Corporation, which resulted from this merger in 1901, illustrated a process under way for 30 years: the combination of independent industrial enterprises into federated or centralized companies. Started during the Civil War, the trend gathered momentum after the 1870s, as businessmen began to fear that overproduction would lead to declining prices and falling profits. They realized that if they could control both production and markets, they could bring competing firms into a single organization. The “corporation” and the “trust” were developed to achieve these ends.

Corporations, making available a deep reservoir of capital and giving business enterprises permanent life and continuity of control, attracted investors both by their anticipated profits and by their limited liability in case of business failure. The trusts were in effect combinations of corporations whereby the stockholders of each placed stocks in the hands of trustees. (The “trust” as a method of corporate consolidation soon gave way to the holding company, but the term stuck.) Trusts made possible large-scale combinations, centralized control and administration, and the pooling of patents. Their larger capital resources provided power to expand, to compete with foreign business organizations, and to drive hard bargains with labor, which was beginning to organize effectively. They could also exact favorable terms from railroads and exercise influence in politics.

The Standard Oil Company, founded by John D. Rockefeller, was one of the earliest and strongest corporations, and was followed rapidly by other combinations – in cottonseed oil, lead, sugar, tobacco, and rubber. Soon aggressive individual businessmen began to mark out industrial domains for themselves. Four great meat packers, chief among them Philip Armour and Gustavus Swift, established a beef trust. Cyrus McCormick achieved preeminence in the reaper business. A 1904 survey showed that more than 5,000 previously independent concerns had been consolidated into some 300 industrial trusts.

The trend toward amalgamation extended to other fields, particularly transportation and communications. Western Union, dominant in telegraphy, was followed by the Bell Telephone System and eventually by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company. In the 1860s, Cornelius Vanderbilt had consolidated 13 separate railroads into a single 800-kilometer line connecting New York City and Buffalo. During the next decade he acquired lines to Chicago, Illinois, and Detroit, Michigan, establishing the New York Central Railroad. Soon the major railroads of the nation were organized into trunk lines and systems directed by a handful of men.

In this new industrial order, the city was the nerve center, bringing to a focus all the nation’s dynamic economic forces: vast accumulations of capital, business, and financial institutions, spreading railroad yards, smoky factories, armies of manual and clerical workers. Villages, attracting people from the countryside and from lands across the sea, grew into towns and towns into cities almost overnight. In 1830 only one of every 15 Americans lived in communities of 8,000 or more; in 1860 the ratio was nearly one in every six; and in 1890 three in every 10. No single city had as many as a million inhabitants in 1860; but 30 years later New York had a million and a half; Chicago, Illinois, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, each had over a million. In these three decades, Philadelphia and Baltimore, Maryland, doubled in population; Kansas City, Missouri, and Detroit, Michigan, grew fourfold; Cleveland, Ohio, sixfold; Chicago, tenfold. Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Omaha, Nebraska, and many communities like them – hamlets when the Civil War began – increased 50 times or more in population.

RAILROADS, REGULATIONS, AND THE TARIFF

Railroads were especially important to the expanding nation, and their practices were often criticized. Rail lines extended cheaper freight rates to large shippers by rebating a portion of the charge, thus disadvantaging small shippers. Freight rates also frequently were not proportionate to distance traveled; competition usually held down charges between cities with several rail connections. Rates tended to be high between points served by only one line. Thus it cost less to ship goods 1,280 kilometers from Chicago to New York than to places a few hundred kilometers from Chicago. Moreover, to avoid competition rival companies sometimes divided (“pooled”) the freight business according to a prearranged scheme that placed the total earnings in a common fund for distribution.

Popular resentment at these practices stimulated state efforts at regulation, but the problem was national in character. Shippers demanded congressional action. In 1887 President Grover Cleveland signed the Interstate Commerce Act, which forbade excessive charges, pools, rebates, and rate discrimination. It created an Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to oversee the act, but gave it little enforcement power. In the first decades of its existence, virtually all the ICC’s efforts at regulation and rate reductions failed to pass judicial review.

President Cleveland also opposed the protective tariff on foreign goods, which had come to be accepted as permanent national policy under the Republican presidents who dominated the politics of the era. Cleveland, a conservative Democrat, regarded tariff protection as an unwarranted subsidy to big business, giving the trusts pricing power to the disadvantage of ordinary Americans. Reflecting the interests of their Southern base, the Democrats had reverted to their pre-Civil War opposition to protection and advocacy of a “tariff for revenue only.”

Cleveland, narrowly elected in 1884, was unsuccessful in achieving tariff reform during his first term. He made the issue the keynote of his campaign for reelection, but Republican candidate Benjamin Harrison, a defender of protectionism, won in a close race. In 1890, the Harrison administration, fulfilling its campaign promises, achieved passage of the McKinley tariff, which increased the already high rates. Blamed for high retail prices, the McKinley duties triggered widespread dissatisfaction, led to Republican losses in the 1890 elections, and paved the way for Cleveland’s return to the presidency in the 1892 election.

During this period, public antipathy toward the trusts increased. The nation’s gigantic corporations were subjected to bitter attack through the 1880s by reformers such as Henry George and Edward Bellamy. The Sherman Antitrust Act, passed in 1890, forbade all combinations in restraint of interstate trade and provided several methods of enforcement with severe penalties. Couched in vague generalities, the law accomplished little immediately after its passage. But a decade later, President Theodore Roosevelt would use it vigorously.

REVOLUTION IN AGRICULTURE

Despite the great gains in industry, agriculture remained the nation’s basic occupation. The revolution in agriculture – paralleling that in manufacturing after the Civil War – involved a shift from hand labor to machine farming, and from subsistence to commercial agriculture. Between 1860 and 1910, the number of farms in the United States tripled, increasing from two million to six million, while the area farmed more than doubled from 160 million to 352 million hectares.

Between 1860 and 1890, the production of such basic commodities as wheat, corn, and cotton outstripped all previous figures in the United States. In the same period, the nation’s population more than doubled, with the largest growth in the cities. But the American farmer grew enough grain and cotton, raised enough beef and pork, and clipped enough wool not only to supply American workers and their families but also to create ever-increasing surpluses.

Several factors accounted for this extraordinary achievement. One was the expansion into the West. Another was a technological revolution. The farmer of 1800, using a hand sickle, could hope to cut a fifth of a hectare of wheat a day. With the cradle, 30 years later, he might cut four-fifths. In 1840 Cyrus McCormick performed a miracle by cutting from two to two-and-a-half hectares a day with the reaper, a machine he had been developing for nearly 10 years. He headed west to the young prairie town of Chicago, where he set up a factory – and by 1860 sold a quarter of a million reapers.

Other farm machines were developed in rapid succession: the automatic wire binder, the threshing machine, and the reaper-thresher or combine. Mechanical planters, cutters, huskers, and shellers appeared, as did cream separators, manure spreaders, potato planters, hay driers, poultry incubators, and a hundred other inventions.

Scarcely less important than machinery in the agricultural revolution was science. In 1862 the Morrill Land Grant College Act allotted public land to each state for the establishment of agricultural and industrial colleges. These were to serve both as educational institutions and as centers for research in scientific farming. Congress subsequently appropriated funds for the creation of agricultural experiment stations throughout the country and granted funds directly to the Department of Agriculture for research purposes. By the beginning of the new century, scientists throughout the United States were at work on a wide variety of agricultural projects.

One of these scientists, Mark Carleton, traveled for the Department of Agriculture to Russia. There he found and exported to his homeland the rust- and drought-resistant winter wheat that now accounts for more than half the U.S. wheat crop. Another scientist, Marion Dorset, conquered the dreaded hog cholera, while still another, George Mohler, helped prevent hoof-and-mouth disease. From North Africa, one researcher brought back Kaffir corn; from Turkestan, another imported the yellow‑flowering alfalfa. Luther Burbank in California produced scores of new fruits and vegetables; in Wisconsin, Stephen Babcock devised a test for determining the butterfat content of milk; at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the African-American scientist George Washington Carver found hundreds of new uses for the peanut, sweet potato, and soybean.

In varying degrees, the explosion in agricultural science and technology affected farmers all over the world, raising yields, squeezing out small producers, and driving migration to industrial cities. Railroads and steamships, moreover, began to pull regional markets into one large world market with prices instantly communicated by trans-Atlantic cable as well as ground wires. Good news for urban consumers, falling agricultural prices threatened the livelihood of many American farmers and touched off a wave of agrarian discontent.

THE DIVIDED SOUTH

After Reconstruction, Southern leaders pushed hard to attract industry. States offered large inducements and cheap labor to investors to develop the steel, lumber, tobacco, and textile industries. Yet in 1900 the region’s percentage of the nation’s industrial base remained about what it had been in 1860. Moreover, the price of this drive for industrialization was high: Disease and child labor proliferated in Southern mill towns. Thirty years after the Civil War, the South was still poor, overwhelmingly agrarian, and economically dependent. Moreover, its race relations reflected not just the legacy of slavery, but what was emerging as the central theme of its history – a determination to enforce white supremacy at any cost.

Intransigent white Southerners found ways to assert state control to maintain white dominance. Several Supreme Court decisions also bolstered their efforts by upholding traditional Southern views of the appropriate balance between national and state power.

In 1873 the Supreme Court found that the 14th Amendment (citizenship rights not to be abridged) conferred no new privileges or immunities to protect African Americans from state power. In 1883, furthermore, it ruled that the 14th Amendment did not prevent individuals, as opposed to states, from practicing discrimination. And in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Court found that “separate but equal” public accommodations for African Americans, such as trains and restaurants, did not violate their rights. Soon the principle of segregation by race extended into every area of Southern life, from railroads to restaurants, hotels, hospitals, and schools. Moreover, any area of life that was not segregated by law was segregated by custom and practice. Further curtailment of the right to vote followed. Periodic lynchings by mobs underscored the region’s determination to subjugate its African-American population.

Faced with pervasive discrimination, many African Americans followed Booker T. Washington, who counseled them to focus on modest economic goals and to accept temporary social discrimination. Others, led by the African-American intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois, wanted to challenge segregation through political action. But with both major parties uninterested in the issue and scientific theory of the time generally accepting black inferiority, demands for racial justice attracted little support.

THE LAST FRONTIER

In 1865 the frontier line generally followed the western limits of the states bordering the Mississippi River, but bulged outward beyond the eastern sections of Texas, Kansas, and Nebraska. Then, running north and south for nearly 1,600 kilometers, loomed huge mountain ranges, many rich in silver, gold, and other metals. To their west, plains and deserts stretched to the wooded coastal ranges and the Pacific Ocean. Apart from the settled districts in California and scattered outposts, the vast inland region was populated by Native Americans: among them the Great Plains tribes – Sioux and Blackfoot, Pawnee and Cheyenne – and the Indian cultures of the Southwest, including Apache, Navajo, and Hopi.

A mere quarter-century later, virtually all this country had been carved into states and territories. Miners had ranged over the whole of the mountain country, tunneling into the earth, establishing little communities in Nevada, Montana, and Colorado. Cattle ranchers, taking advantage of the enormous grasslands, had laid claim to the huge expanse stretching from Texas to the upper Missouri River. Sheep herders had found their way to the valleys and mountain slopes. Farmers sank their plows into the plains and closed the gap between the East and West. By 1890 the frontier line had disappeared.

Settlement was spurred by the Homestead Act of 1862, which granted free farms of 64 hectares to citizens who would occupy and improve the land. Unfortunately for the would-be farmers, much of the Great Plains was suited more for cattle ranching than farming, and by 1880 nearly 22,400,000 hectares of “free” land was in the hands of cattlemen or the railroads.

In 1862 Congress also voted a charter to the Union Pacific Railroad, which pushed westward from Council Bluffs, Iowa, using mostly the labor of ex-soldiers and Irish immigrants. At the same time, the Central Pacific Railroad began to build eastward from Sacramento, California, relying heavily on Chinese immigrant labor. The whole country was stirred as the two lines steadily approached each other, finally meeting on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Point in Utah. The months of laborious travel hitherto separating the two oceans was now cut to about six days. The continental rail network grew steadily; by 1884 four great lines linked the central Mississippi Valley area with the Pacific.

The first great rush of population to the Far West was drawn to the mountainous regions, where gold was found in California in 1848, in Colorado and Nevada 10 years later, in Montana and Wyoming in the 1860s, and in the Black Hills of the Dakota country in the 1870s. Miners opened up the country, established communities, and laid the foundations for more permanent settlements. Eventually, however, though a few communities continued to be devoted almost exclusively to mining, the real wealth of Montana, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, and California proved to be in the grass and soil. Cattle-raising, long an important industry in Texas, flourished after the Civil War, when enterprising men began to drive their Texas longhorn cattle north across the open public land. Feeding as they went, the cattle arrived at railway shipping points in Kansas, larger and fatter than when they started. The annual cattle drive became a regular event; for hundreds of kilometers, trails were dotted with herds moving northward.

Next, immense cattle ranches appeared in Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakota territory. Western cities flourished as centers for the slaughter and dressing of meat. The cattle boom peaked in the mid-1880s. By then, not far behind the rancher creaked the covered wagons of the farmers bringing their families, their draft horses, cows, and pigs. Under the Homestead Act they staked their claims and fenced them with a new invention, barbed wire. Ranchers were ousted from lands they had roamed without legal title.

Ranching and the cattle drives gave American mythology its last icon of frontier culture – the cowboy. The reality of cowboy life was one of grueling hardship. As depicted by writers like Zane Grey and such movie actors as John Wayne, the cowboy was a powerful mythological figure, a bold, virtuous man of action. Not until the late 20th century did a reaction set in. Historians and filmmakers alike began to depict “the Wild West” as a sordid place, peopled by characters more apt to reflect the worst, rather than the best, in human nature.

THE PLIGHT OF THE NATIVE AMERICANS

As in the East, expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers, and settlers led to increasing conflicts with the Native Americans of the West. Many tribes of Native Americans – from the Utes of the Great Basin to the Nez Perces of Idaho – fought the whites at one time or another. But the Sioux of the Northern Plains and the Apache of the Southwest provided the most significant opposition to frontier advance. Led by such resourceful leaders as Red Cloud and Crazy Horse, the Sioux were particularly skilled at high-speed mounted warfare. The Apaches were equally adept and highly elusive, fighting in their environs of desert and canyons.

Conflicts with the Plains Indians worsened after an incident where the Dakota (part of the Sioux nation), declaring war against the U.S. government because of long-standing grievances, killed five white settlers. Rebellions and attacks continued through the Civil War. In 1876 the last serious Sioux war erupted, when the Dakota gold rush penetrated the Black Hills. The Army was supposed to keep miners off Sioux hunting grounds, but did little to protect the Sioux lands. When ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range according to their treaty rights, however, it moved quickly and vigorously.

In 1876, after several indecisive encounters, Colonel George Custer, leading a small detachment of cavalry encountered a vastly superior force of Sioux and their allies on the Little Bighorn River. Custer and his men were completely annihilated. Nonetheless the Native-American insurgency was soon suppressed. Later, in 1890, a ghost dance ritual on the Northern Sioux reservation at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, led to an uprising and a last, tragic encounter that ended in the death of nearly 300 Sioux men, women, and children.

Long before this, however, the way of life of the Plains Indians had been destroyed by an expanding white population, the coming of the railroads, and the slaughter of the buffalo, almost exterminated in the decade after 1870 by the settlers’ indiscriminate hunting.

The Apache wars in the Southwest dragged on until Geronimo, the last important chief, was captured in 1886.

Government policy ever since the Monroe administration had been to move the Native Americans beyond the reach of the white frontier. But inevitably the reservations had become smaller and more crowded. Some Americans began to protest the government’s treatment of Native Americans. Helen Hunt Jackson, for example, an Easterner living in the West, wrote A Century of Dishonor (1881), which dramatized their plight and struck a chord in the nation’s conscience. Most reformers believed the Native American should be assimilated into the dominant culture. The federal government even set up a school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in an attempt to impose white values and beliefs on Native-American youths. (It was at this school that Jim Thorpe, often considered the best athlete the United States has produced, gained fame in the early 20th century.)

In 1887 the Dawes (General Allotment) Act reversed U.S. Native-American policy, permitting the president to divide up tribal land and parcel out 65 hectares of land to each head of a family. Such allotments were to be held in trust by the government for 25 years, after which time the owner won full title and citizenship. Lands not thus distributed, however, were offered for sale to settlers. This policy, however well-intentioned, proved disastrous, since it allowed more plundering of Native-American lands. Moreover, its assault on the communal organization of tribes caused further disruption of traditional culture. In 1934 U.S. policy was reversed yet again by the Indian Reorganization Act, which attempted to protect tribal and communal life on the reservations.

AMBIVALENT EMPIRE

The last decades of the 19th century were a period of imperial expansion for the United States. The American story took a different course from that of its European rivals, however, because of the U.S. history of struggle against European empires and its unique democratic development.

The sources of American expansionism in the late 19th century were varied. Internationally, the period was one of imperialist frenzy, as European powers raced to carve up Africa and competed, along with Japan, for influence and trade in Asia. Many Americans, including influential figures such as Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Elihu Root, felt that to safeguard its own interests, the United States had to stake out spheres of economic influence as well. That view was seconded by a powerful naval lobby, which called for an expanded fleet and network of overseas ports as essential to the economic and political security of the nation. More generally, the doctrine of “manifest destiny,” first used to justify America’s continental expansion, was now revived to assert that the United States had a right and duty to extend its influence and civilization in the Western Hemisphere and the Caribbean, as well as across the Pacific.

At the same time, voices of anti-imperialism from diverse coalitions of Northern Democrats and reform-minded Republicans remained loud and constant. As a result, the acquisition of a U.S. empire was piecemeal and ambivalent. Colonial-minded administrations were often more concerned with trade and economic issues than political control.

The United States’ first venture beyond its continental borders was the purchase of Alaska – sparsely populated by Inuit and other native peoples – from Russia in 1867. Most Americans were either indifferent to or indignant at this action by Secretary of State William Seward, whose critics called Alaska “Seward’s Folly” and “Seward’s Icebox.” But 30 years later, when gold was discovered on Alaska’s Klondike River, thousands of Americans headed north, and many of them settled in Alaska permanently. When Alaska became the 49th state in 1959, it replaced Texas as geographically the largest state in the Union.

The Spanish-American War, fought in 1898, marked a turning point in U.S. history. It left the United States exercising control or influence over islands in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific.

By the 1890s, Cuba and Puerto Rico were the only remnants of Spain’s once vast empire in the New World, and the Philippine Islands comprised the core of Spanish power in the Pacific. The outbreak of war had three principal sources: popular hostility to autocratic Spanish rule in Cuba; U.S. sympathy with the Cuban fight for independence; and a new spirit of national assertiveness, stimulated in part by a nationalistic and sensationalist press.

By 1895 Cuba’s growing restiveness had become a guerrilla war of independence. Most Americans were sympathetic with the Cubans, but President Cleveland was determined to preserve neutrality. Three years later, however, during the administration of William McKinley, the U.S. warship Maine, sent to Havana on a “courtesy visit” designed to remind the Spanish of American concern over the rough handling of the insurrection, blew up in the harbor. More than 250 men were killed. The Maine was probably destroyed by an accidental internal explosion, but most Americans believed the Spanish were responsible. Indignation, intensified by sensationalized press coverage, swept across the country. McKinley tried to preserve the peace, but within a few months, believing delay futile, he recommended armed intervention.

The war with Spain was swift and decisive. During the four months it lasted, not a single American reverse of any importance occurred. A week after the declaration of war, Commodore George Dewey, commander of the six-warship Asiatic Squadron then at Hong Kong, steamed to the Philippines. Catching the entire Spanish fleet at anchor in Manila Bay, he destroyed it without losing an American life.

Meanwhile, in Cuba, troops landed near Santiago, where, after winning a rapid series of engagements, they fired on the port. Four armored Spanish cruisers steamed out of Santiago Bay to engage the American navy and were reduced to ruined hulks.

From Boston to San Francisco, whistles blew and flags waved when word came that Santiago had fallen. Newspapers dispatched correspondents to Cuba and the Philippines, who trumpeted the renown of the nation’s new heroes. Chief among them were Commodore Dewey and Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, who had resigned as assistant secretary of the navy to lead his volunteer regiment, the “Rough Riders,” to service in Cuba. Spain soon sued for an end to the war. The peace treaty signed on December 10, 1898, transferred Cuba to the United States for temporary occupation preliminary to the island’s independence. In addition, Spain ceded Puerto Rico and Guam in lieu of war indemnity, and the Philippines for a U.S. payment of $20 million.

Officially, U.S. policy encouraged the new territories to move toward democratic self-government, a political system with which none of them had any previous experience. In fact, the United States found itself in a colonial role. It maintained formal administrative control in Puerto Rico and Guam, gave Cuba only nominal independence, and harshly suppressed an armed independence movement in the Philippines. (The Philippines gained the right to elect both houses of its legislature in 1916. In 1936 a largely autonomous Philippine Commonwealth was established. In 1946, after World War II, the islands finally attained full independence.)

U.S. involvement in the Pacific area was not limited to the Philippines. The year of the Spanish-American War also saw the beginning of a new relationship with the Hawaiian Islands. Earlier contact with Hawaii had been mainly through missionaries and traders. After 1865, however, American investors began to develop the islands’ resources – chiefly sugar cane and pineapples.

When the government of Queen Liliuokalani announced its intention to end foreign influence in 1893, American businessmen joined with influential Hawaiians to depose her. Backed by the American ambassador to Hawaii and U.S. troops stationed there, the new government then asked to be annexed to the United States. President Cleveland, just beginning his second term, rejected annexation, leaving Hawaii nominally independent until the Spanish-American War, when, with the backing of President McKinley, Congress ratified an annexation treaty. In 1959 Hawaii would become the 50th state.

To some extent, in Hawaii especially, economic interests had a role in American expansion, but to influential policy makers such as Roosevelt, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, and Secretary of State John Hay, and to influential strategists such as Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, the main impetus was geostrategic. For these people, the major dividend of acquiring Hawaii was Pearl Harbor, which would become the major U.S. naval base in the central Pacific. The Philippines and Guam complemented other Pacific bases – Wake Island, Midway, and American Samoa. Puerto Rico was an important foothold in a Caribbean area that was becoming increasingly important as the United States contemplated a Central American canal.

U.S. colonial policy tended toward democratic self-government. As it had done with the Philippines, in 1917 the U.S. Congress granted Puerto Ricans the right to elect all of their legislators. The same law also made the island officially a U.S. territory and gave its people American citizenship. In 1950 Congress granted Puerto Rico complete freedom to decide its future. In 1952, the citizens voted to reject either statehood or total independence, and chose instead a commonwealth status that has endured despite the efforts of a vocal separatist movement. Large numbers of Puerto Ricans have settled on the mainland, to which they have free access and where they enjoy all the political and civil rights of any other citizen of the United States.

THE CANAL AND THE AMERICAS

The war with Spain revived U.S. interest in building a canal across the isthmus of Panama, uniting the two great oceans. The usefulness of such a canal for sea trade had long been recognized by the major commercial nations of the world; the French had begun digging one in the late 19th century but had been unable to overcome the engineering difficulties. Having become a power in both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, the United States saw a canal as both economically beneficial and a way of providing speedier transfer of warships from one ocean to the other.

At the turn of the century, what is now Panama was the rebellious northern province of Colombia. When the Colombian legislature in 1903 refused to ratify a treaty giving the United States the right to build and manage a canal, a group of impatient Panamanians, with the support of U.S. Marines, rose in rebellion and declared Panamanian independence. The breakaway country was immediately recognized by President Theodore Roosevelt. Under the terms of a treaty signed that November, Panama granted the United States a perpetual lease to a 16-kilometer-wide strip of land (the Panama Canal Zone) between the Atlantic and the Pacific, in return for $10 million and a yearly fee of $250,000. Colombia later received $25 million as partial compensation. Seventy-five years later, Panama and the United States negotiated a new treaty. It provided for Panamanian sovereignty in the Canal Zone and transfer of the canal to Panama on December 31, 1999.

The completion of the Panama Canal in 1914, directed by Colonel George W. Goethals, was a major triumph of engineering. The simultaneous conquest of malaria and yellow fever made it possible and was one of the 20th century’s great feats in preventive medicine.

Elsewhere in Latin America, the United States fell into a pattern of fitful intervention. Between 1900 and 1920, the United States carried out sustained interventions in six Western Hemispheric nations – most notably Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. Washington offered a variety of justifications for these interventions: to establish political stability and democratic government, to provide a favorable environment for U.S. investment (often called dollar diplomacy), to secure the sea lanes leading to the Panama Canal, and even to prevent European countries from forcibly collecting debts. The United States had pressured the French into removing troops from Mexico in 1867. Half a century later, however, as part of an ill-starred campaign to influence the Mexican revolution and stop raids into American territory, President Woodrow Wilson sent 11,000 troops into the northern part of the country in a futile effort to capture the elusive rebel and outlaw Francisco “Pancho” Villa.

Exercising its role as the most powerful – and most liberal – of Western Hemisphere nations, the United States also worked to establish an institutional basis for cooperation among the nations of the Americas. In 1889 Secretary of State James G. Blaine proposed that the 21 independent nations of the Western Hemisphere join in an organization dedicated to the peaceful settlement of disputes and to closer economic bonds. The result was the Pan-American Union, founded in 1890 and known today as the Organization of American States (OAS).

The later administrations of Herbert Hoover (1929-33) and Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-45) repudiated the right of U.S. intervention in Latin America. In particular, Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy of the 1930s, while not ending all tensions between the United States and Latin America, helped dissipate much of the ill-will engendered by earlier U.S. intervention and unilateral actions.

UNITED STATES AND ASIA

Newly established in the Philippines and firmly entrenched in Hawaii at the turn of the century, the United States had high hopes for a vigorous trade with China. However, Japan and various European nations had acquired established spheres of influence there in the form of naval bases, leased territories, monopolistic trade rights, and exclusive concessions for investing in railway construction and mining.

Idealism in American foreign policy existed alongside the desire to compete with Europe’s imperial powers in the Far East. The U.S. government thus insisted as a matter of principle upon equality of commercial privileges for all nations. In September 1899, Secretary of State John Hay advocated an “Open Door” for all nations in China – that is, equality of trading opportunities (including equal tariffs, harbor duties, and railway rates) in the areas Europeans controlled. Despite its idealistic component, the Open Door, in essence, was a diplomatic maneuver that sought the advantages of colonialism while avoiding the stigma of its frank practice. It had limited success.

With the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, the Chinese struck out against foreigners. In June, insurgents seized Beijing and attacked the foreign legations there. Hay promptly announced to the European powers and Japan that the United States would oppose any disturbance of Chinese territorial or administrative rights and restated the Open Door policy. Once the rebellion was quelled, Hay protected China from crushing indemnities. Primarily for the sake of American good will, Great Britain, Germany, and lesser colonial powers formally affirmed the Open Door policy and Chinese independence. In practice, they consolidated their privileged positions in the country.

A few years later, President Theodore Roosevelt mediated the deadlocked Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, in many respects a struggle for power and influence in the northern Chinese province of Manchuria. Roosevelt hoped the settlement would provide open-door opportunities for American business, but the former enemies and other imperial powers succeeded in shutting the Americans out. Here as elsewhere, the United States was unwilling to deploy military force in the service of economic imperialism. The president could at least content himself with the award of the Nobel Peace Prize (1906). Despite gains for Japan, moreover, U.S. relations with the proud and newly assertive island nation would be intermittently difficult through the early decades of the 20th century.