国務省出版物

米国の歴史の概要 – 初期の米国

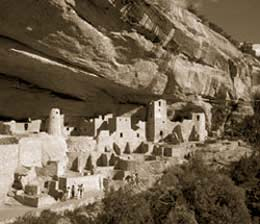

コロラド州にあるメサ・ベルデ集落(13世紀)

©Russ Finley/Finley-Holiday

氷河期の最中だった紀元前3万4000年~3万年には、世界中の水の大半が広大な大陸氷床として凍りついていた。その結果、当時のベーリング海の水位は現在より何百メートルも低く、アジア大陸と北米大陸の間に「ベリンジア」と呼ばれる陸の橋が出現していた。ベリンジアは、最も広いときには、幅がおよそ1,500キロメートルに達していたと考えられている。ベリンジアは、木のない湿ったツンドラで、草や植生に覆われていたため、大きな動物が集まり、初期の人類は生存するためにそうした動物を求めて狩りをした。

北米大陸に到達した最初の人類が、自分では気づかないうちに、新しい大陸に渡ってきたことは、ほぼ間違いない。彼らは何千年もの間、先祖たちがしてきたように、シベリアの海岸に沿って狩りをし、獲物を追ってそのまま陸の橋を渡ってきたものと思われる。

これらの最初の北米人が、今のアラスカ州に到達してから、大氷河の間を縫って南下し、現在の米国へ達するまでには、さらに何千年もの年月がかかったことだろう。初期の北米に人が住んでいたことを示す証拠は、続々と発見されている。しかし、その中で紀元前1万2000年より古いことが確実に証明できるものは、ほとんどない。例えば、最近アラスカ州北部で発見された狩猟用の見張り台は、ほぼその時代まで遡るものかもしれない。また、ニューメキシコ州クロービス市の近くで発見された、精巧に作られた槍の穂先などの器物も同様であるかもしれない。

北米および南米の各地で、同様の工芸品が発見されており、おそらく紀元前1万年より前には、すでに西半球のほとんどで人類が生活を築いていたことを示している。そのころマンモスが死滅し始め、代わってバイソンが、こうした初期の北米人の食料と毛皮の主な供給源となった。それから時を経て、乱獲や自然の原因で絶滅する大型の獲物が増えるにつれ、植物、木の実、種などが、初期のアメリカ人の食糧源として重要性を増し始めた。そして徐々に、採食と原始的な初期の農業が行われるようになった。その先駆者は、現在のメキシコ中部にいたアメリカ先住民で、彼らは、恐らく紀元前8000年には、すでにトウモロコシ、スカッシュ(カボチャ類)、豆類などを栽培していた。こうした農業の知識は、徐々に北へ広がっていった。

紀元前3000年までには、今のニューメキシコ州とアリゾナ州の河川の流域で、原始的なトウモロコシが栽培されるようになっていた。続いて、初期の灌がいが行われた跡が現れ始め、そして紀元前300年までには、初期の村落の跡が出現し始めていた。

紀元後数世紀までには、現在のアリゾナ州フェニックス市の近くの集落にホホカム族が住んでおり、そこには、球技場やメキシコのピラミッドを思わせるような墳丘、そして運河と灌漑設備があった。

現在の米国にあたる地域で、初めて墳丘(マウンド)を作ったアメリカ先住民は、アデナン族と呼ばれる。彼らは、紀元前600年ごろから、土の墳墓や要塞を築くようになった。その時代の墳丘には、鳥や蛇の形をしたものもあり、おそらく宗教的な目的を持っていたものと思われるが、詳しくはまだ解明されていない。

アデナン族は、「ホープウェリアン族」と総称される様々な部族によって、吸収されるか追放されたものと思われる。ホープウェリアン文化の中枢のひとつは、現在のオハイオ州南部にあり、そこでは今も数千に及ぶ墳丘跡を見ることができる。ホープウェリアン族は優れた交易業者だったとされており、何百キロメートルにもわたる幅広い地域で、道具や材料を使用し交換していた。

紀元500年ごろまでに、ホープウェリアン族も消滅し、徐々にミシシッピアンまたはテンプル・マウンド文化と呼ばれる広範な部族のグループにとって代わられた。イリノイ州コリンズビル市の近くにあるカホキアという町には、12世紀初めのピーク時に、おおよそ2万人が住んでいたと考えられている。この町の中心部には、高さ30メートル、底面積37ヘクタールの頂上が平らな土の墳丘が立っていた。この他にも付近の80カ所で墳丘が発見されている。

カホキアのような町は、狩猟、採集、交易、および農業によって食料や必需品を得ていた。これらの町は、繁栄していた南方の社会の影響を受けて、複雑な階級性社会へと進化し、奴隷を使い、いけにえの習慣も持っていた。

現在の米国南西部にあたる地域では、今のホピ族インディアンの祖先であるアナサズィ族が、900年ごろ、石とアドービ煉瓦のプエブロ住宅を築くようになった。これは大抵、崖の表面に沿って作られたアパート形式の独特の驚くべき建築物で、中でも最も有名なコロラド州メサベルデ市の「崖の宮殿」には、200以上の部屋があった。また、ニューメキシコ州のチャコ川沿いに遺跡のあるプエブロ・ボニトには、かつて800以上の部屋があった。

コロンブス以前の時代のアメリカ先住民の中で最も豊かな暮らしをしていたのは、太平洋岸北西部に住む人々だったと思われる。この地域では、魚や自然の材料が豊富にとれ、十分な食糧があったため、紀元前1000年には、村落での定住が可能だった。彼らの豪華な「ポトラッチ」の祝宴は、おそらく古代アメリカでは他に類を見ないぜいたくなものだったと思われる。

このように、最初のヨーロッパ人を出迎えた米国は、無人の荒野とは程遠かった。今では、当時の西半球には、西ヨーロッパとほぼ同数の人々、すなわちおおよそ4000万人が居住していたと考えられている。ヨーロッパ人による入植が始まった頃、現在の米国に住んでいたアメリカ先住民の数は、200万~1800万人と推定されているが、ほとんどの歴史家は、低い方の推定数を支持している。確実に言えるのは、原住民とヨーロッパ人との文字通り最初の接触の時から、ヨーロッパ人の持ち込んだ疾病が原住民の人口に壊滅的な影響を及ぼしたということである。中でも、天然痘は、いくつもの地域社会を荒廃させ、ヨーロッパ人入植者との多くの戦争や小競り合いにも増して、1600年代のインディアン人口急減の直接の原因となったと考えられている。

当時のインディアンの慣習や文化は、驚くほど多様だった。これは、彼らが広大な土地に住み、様々な環境に適応してきたことを考えれば当然である。しかし、ある程度の共通点を挙げることもできる。ほとんどの部族は、特に森林の多い東部や中西部では食糧供給の手段として、狩猟、採集、そしてトウモロコシなどの栽培を行っていた。多くの場合、女性が農業と食糧配布を担当し、男性の役割は狩猟と戦争への参加だった。

北米大陸のアメリカ先住民の社会は、どこから見ても土地との結び付きが強かった。自然や天候との一体感が信仰の不可欠な要素となっていた。彼らの暮らしは、基本的に一族中心の共同生活であり、当時の欧州の慣習に比べると、子供達は自由で寛容な扱いを受けていた。

北米には特定の文書を保存するために、一種の象形文字を発達させた部族もいたが、アメリカ先住民の文化は主として口承であり、物語や夢の叙述が重視された。明らかに、様々なグループ間の通商が盛んに行われており、また近隣の部族間で、友好的にせよ敵対的にせよ、公式の関係が維持されていたことを示す強力な証拠が存在する。

初めて北米を訪れたヨーロッパ人として、少なくとも確かな証拠が残っているのは、グリーンランドから西へ旅をした古代スカンジナビア人である。グリーンランドには、985年前後に「赤毛のエリック」が入植地を築いていた。1001年に、エリックの息子リーフが、現在のカナダ北東部沿岸を探検し、少なくとも一冬をそこで過ごしたと考えられている。

スカンジナビアの英雄伝によると、バイキングの航海者たちが、北米大陸の大西洋岸を、南はバハマ諸島まで探検したことがうかがわれるが、これはまだ証明されてはいない。しかし、1963年に、ニューファンドランド島北部のランス・オー・メドーズで、古代スカンジナビア人の当時の住宅の跡が発見され、英雄伝の内容が少なくとも一部は裏付けられた。

クリストファー・コロンブスがアジアへの西回りの航路を探してカリブ海の島に上陸後わずか5年後の1497年に、ベネチア人の船長ジョン・カボットが、英国王の命を受けてニューファンドランド島に到着した。カボットの航海は、すぐに人々の記憶から薄れてしまったが、後に英国が北米に対する権利を主張する根拠となった。また、カボットの航海によって、ジョージス・バンクス沖の豊かな漁場が発見され、間もなくポルトガル人をはじめとする欧州の漁船が定期的に訪れるようになった。

コロンブスは、後の米国となる大陸をついに自分の目で見ることはなかったが、彼が設立に貢献したスペイン領地から、初の大陸探検隊が派遣された。その第1回は、1513年に派遣され、ホアン・ポンセ・デ・レオンの率いる探検隊が、現在のフロリダ州沿岸セント・オーガスティン市の近くに上陸した。

スペインは、1522年にメキシコを征服し、西半球における地位をさらに固めた。それに続くいくつかの発見によって、「アメリカ」に関するヨーロッパ人の知識が深まっていった。現在の「アメリカ」という名前は、「新世界」への航海記を書いて広く人気を博したイタリア人、アメリゴ・ベスプッチにちなんで付けられたものである。1529年までには、ラブラドル半島からティエラデルフエゴ島に及ぶ大西洋岸の信頼できる地図が作成されていたが、アジアへの「北西航路」発見の希望が完全に断念されるまでには、さらに1世紀の年月を要することになる。

スペイン人による初期の探検の中で、最も重要なもののひとつは、ヘルナンド・デ・ソトによるものだった。デ・ソトは、ベテランの「征服者」の1人、フランシスコ・ピサロのペルー征服に同行したことのある人物だった。デ・ソトの探検隊は、富を求めて1539年にハバナを出発し、フロリダに上陸して米国南東部を通過し、ミシシッピ川に達した。

同じくスペイン人のフランシスコ・バスケス・デ・コロナドは、1540年にメキシコを出発し、伝説のシボラの7つの町を探しに行った。彼は、グランド・キャニオンやカンザスに到達したが、その仲間たちが探し求めていた黄金や財宝を発見することはできなかった。しかし、コロナドの探検隊は、訪れた地域の人々に、意図せずとして素晴らしい贈り物を残した。探検隊の馬の多数が脱走し、グレート・プレーンズ(大草原地帯)の人々の生活を大きく変えたのである。プレーンズ・インディアンは、その後数世代の間に、馬術の名人となり、活動の範囲と規模を大きく広げた。

スペイン人が南から北上している間に、現在の米国北部は、ジョバンニ・ダ・ベラザノなどの探検家によって、徐々に世に知られるようになった。ベラザノは、フランス王室のために航海をしていたフローレンス人で、1524年にノースカロライナに上陸した後、大西洋岸に沿って北へ航海し、現在のニューヨーク湾の先まで到達した。

その10年後、フランス人ジャック・カルティエが、それまでのヨーロッパ人と同様、アジアへの航路を発見する夢を抱いて出発した。カルティエは、セント・ローレンス川沿いを探検し、北米におけるフランスの請求権の根拠を築いた。この権利は1763年まで続くことになった。

フランスのユグノー教徒たちが最初にケベックに築いた入植地は、1540年代に崩壊したが、その20年後、彼らはフロリダ北部沿岸に定住を試みた。スペイン人は、これらのフランス人をメキシコ湾流沿いのスペインの貿易路を脅かすものと見なし、1565年にユグノー入植地を破壊した。皮肉なことに、間もなくスペイン軍の指揮官ペドロ・メンデスが、そこからそう遠くないところに、セント・オーガスティンの町を作ることになる。セント・オーガスティンは、米国で最も古い、ヨーロッパ人による入植地である。

メキシコ、カリブ諸島、そしてペルーにある植民地から、スペインに多大な富が流入したことは、他の欧州諸国の大きな関心を引いた。英国などの台頭しつつあった海洋国は、フランシス・ドレークが財宝を積んだスペイン船略奪に成功していたこともあって、新世界に関心を持ち始めた。

北西航路の探求に関する論文を書いたハンフリー・ギルバートは、1578年に、エリザベス英女王から他の欧州諸国がまだ領有を主張していない新世界の「異教徒と野蛮の荒地」を植民地とする特許状を与えられた。ギルバートは、5年後にその探検を開始した。しかし、彼は海上で行方不明となり、異父弟のウォルター・ローリーが使命を引き継いだ。

ローリーは1585年、ノースカロライナ沖のロアノーク島に北米初の英国植民地を設立した。この入植地は後に放棄され、2年後に設立された2番目の入植地も失敗に終わった。英国が再び入植に挑戦したのは、それから20年も後のことだった。この植民地、すなわち1607年に設立されたジェームズタウンは成功し、北米は新たな時代に入った。

1600年代初めには、欧州から北米へ巨大な移民の波が押し寄せ始めた。その後3世紀以上にわたって、この流れは数百人の英国人による入植から、何百万人もの新しい移民の波へと拡大していった。彼らは様々な強い動機に駆り立てられて、北米大陸の北部に新たな文明を築いた。

英国からの最初の移民が、現在の米国に向かって大西洋を渡ったのは、繁栄するスペインの植民地がメキシコ、西インド諸島、および南米に確立されてから、かなり後のことだった。新世界への初期の入植者と同様、英国からの移民も小さな船に詰め込まれて海を渡った。6~12週間の航海の間、配給される食糧は乏しかった。大勢の人が病気で死に、船は頻繁に嵐に襲われ、波間に消える船もあった。

欧州からの移民の大半は、政治的抑圧を逃れたり、信教の自由を求めたり、あるいは母国では得られない機会を求めたりするために新世界を目指した。1620年から1635年までは、英国中が不景気に見舞われ、仕事の見つからない者が多かった。腕のいい職人でも、かろうじて生計を立てられる程度の収入しか得られなかった。農作物の不作が、さらに状況を悪化させた。そして、商業革命によって繊維産業の萌芽が生まれ、織機の稼動を続けるために、羊毛供給の増大が求められた。地主は農地を囲い込み、牧羊のために農民を追い出した。植民地の拡大は、この行き場を失った農民のはけ口となったのである。

入植者が新しい土地で最初に目にしたのは、見渡す限りの深い森だった。カボチャ類、豆、トウモロコシなど原産の作物の栽培を教えてくれた親切なインディアンの助けがなければ、入植者たちは生き残ることができなかったかもしれない。また、東海岸沿いに2100キロメートルにわたって広がる広大な原生林も、狩猟の獲物や薪、そして住宅、家具、輸出品を作るための原材料の宝庫となった。

この新大陸は、実に豊かな自然に恵まれていたが、入植者が自ら生産することのできない物品に関しては、欧州との交易に頼らなければならなかった。東海岸は移民にとって好都合だった。東海岸全体には多くの入り江や港湾があった。外航船用の港湾がないのは、ノースカロライナとニュージャージー南部の2つの地域だけだった。

ケネベック、ハドソン、デラウェア、サスケハナ、ポトマックをはじめとする多くの雄大な河川が、海岸とアパラチア山脈の間の土地を海につなぐ役割を果たした。しかし、五大湖および大陸の中心部への水路となったのは、カナダのフランス人が支配していたセント・ローレンス川だけだった。深い森林、一部のインディアン部族の抵抗、そしてアパラチア山脈という大きな障壁によって、海岸平野部から奥への入植は妨げられた。その荒野へ踏み込んで行ったのは、毛皮猟師と交易商人に限られていた。最初の100年の間、入植者は海岸沿いにこぢんまりした定住地を作っていた。

政治的な理由に影響され、多くの人々が米国に移住した。1630年代には、英国のチャールズ1世の専制政治が移民に拍車をかけた。その後、1640年代に、オリバー・クロムウェルの率いる反対派がチャールズ1世に対する革命を起こして勝利を収めると、国王に仕えた大勢の騎士が、バージニアに新天地を求めた。欧州のドイツ語圏で、様々な小国の君主が実施した特に宗教に関する抑圧的な政策と、 長期にわたる連続的な戦争の惨禍が、17世紀末から18世紀にかけて、米国への移住を急増させた。

米国への旅は、慎重な計画と対処能力を必要としただけでなく、費用とリスクも大きかった。入植者は、海を渡って5000キロメートル近い旅をしなければならなかった。調理器具、衣服、種子、工具、建材、家畜、武器、弾薬などを持っていく必要があった。時代を異にする他の諸国の植民政策とは対照的に、英国からの移民は政府ではなく、主に営利を目的とする民間の団体に直接支援されていた。

北米に初めて根を下ろした英国の入植地は、ジェームズタウンだった。英国王ジェームズ1世がバージニア会社(あるいはロンドン会社)に与えた特許状に基づいて、1607年におよそ100人の男性の集団が、チェサピーク湾を目指して出発した。彼らは、スペイン人との衝突を避けるため、湾からジェームズ川を約60キロメートル上ったところにある場所を選んだ。

この入植者たちは、農業より黄金探しに関心のある都会出身者や冒険家の集団であり、荒野で全く新しい生活を始める気力も能力も不足していた。その中で、ジョン・スミス船長が有力者として台頭した。論争、飢餓、そしてアメリカ先住民による攻撃といった問題があったにもかかわらず、規律を守らせるスミスの能力によって、この小さな植民地は最初の1年間を切り抜けた。

1609年にスミス船長が英国に帰国すると、彼のいないジェームズタウンは無秩序に陥った。1609年から1610年にかけての冬の間に、入植者の大半が病に倒れた。当時の入植者300人のうち、1610年5月の時点で生存していたのは、わずか60人だった。同年、ジェームズ川をさらにさかのぼったところに、ヘンリコの町(現在のリッチモンド市)が設立された。

その後間もなく、バージニアの経済に大変革をもたらす新たな事態が起きた。1612年、ジョン・ロルフが西インド諸島から輸入したタバコの種を土着の種と掛け合わせ、ヨーロッパ人の嗜好に合う新種のタバコの生産を始めたのである。このタバコの最初の船荷は1614年にロンドンに到着し、10年もたたないうちに、バージニアの主要な収入源となった。

しかし、繁栄はすぐには訪れず、病気やインディアンの襲撃による死亡率も、依然として驚くほど高かった。1607年から1624年までの間に、ジェームズタウンには、おおよそ1万4000人が移住したが、1624年の時点での生存者数は、わずか1132人であった。同年、英国王は王立委員会の勧告に従って、バージニア会社を解散させ、ジェームズタウンを直轄植民地とした。

16世紀の宗教の変動期に、清教徒(ピューリタン)と呼ばれる男女の一団が英国国教会を内部から改革しようとした。基本的に、彼らはローマ・カトリック教に基づく儀式と組織に代わって、より簡素なカルビン派プロテスタントの信仰と礼拝の形式を採用することを要求した。清教徒の改革思想は、国教会の統一性を破壊することによって国民を分裂させ、王室の権限を弱めかねない脅威となった。

1607年、英国国教会の改革は不可能だと考える急進的な清教徒の一派である「分離派」という小集団が、オランダのライデン市へ向かい、そこで亡命を認められた。しかし、カルビン派のオランダ人は、彼らに低賃金の肉体労働しか与えなかった。分離派教会の中には、こうした差別に不満を募らせる者が現われ、新世界への移住を決心した。

1620年、ライデン市の清教徒の一団が、バージニア会社から土地特許状を確保した。総勢101人の清教徒たちは、メイフラワー号でバージニアへ向けて出航した。彼らは嵐のため、はるか北へ流され、ニューイングランドのケープコッドに上陸した。彼らは、自分たちがいかなる政府組織の管轄にも属していないと考え、自分たちで選んだ指導者によって起草された「公正かつ平等な法」に従うことを定めた正式な協定を起草した。これが「メイフラワー誓約書」である。

メイフラワー号は、12月にプリマス湾に到着した。そして、いわゆる「ピルグリム・ファーザーズ」は、冬の間に植民地の建設を始めた。入植者の半数近くが寒さと病気のため死亡したが、近くに住むワンパノーグ族のインディアンが生き延びるための情報を教えてくれた。それはトウモロコシの栽培方法だった。翌年の秋までにはトウモロコシが豊富にとれ、また毛皮や木材の貿易も増えつつあった。

1630年には、英国王チャールズ1世から植民地建設の特許を得た新たな移民の波が、マサチューセッツ湾に到達した。その多くは清教徒であった。英国では清教徒の宗教の行為がますます禁じられるようになっていた。清教徒の指導者ジョン・ウィンスロップは、新世界に「山の上にある町」を築き、そこで宗教的信条に厳しく従った生活をし、すべてのキリスト教徒の模範となるよう、信者を促した。

このマサチューセッツ湾植民地は、ニューイングランド地域全体の開発に重要な役割を果たすことになった。その理由の1つは、ウィンスロップと仲間の清教徒たちが、特許状を持参することができたことにある。かくして、この植民地の統治の権限は、英国ではなくマサチューセッツに存在したのである。

この特許状の規定の下では、権力は「自由民」から成る総会に帰属していた。清教徒あるいは会衆派教会の信徒であることが「自由民」の資格だった。このため、この植民地においては、清教徒が宗教的にも政治的にも優勢となることが保証されていた。総会が総督を選出したが、その後ほぼ1世代の間は、ジョン・ウィンスロップが総督に選ばれた。

清教徒による統治の厳格な正統性を全員が気に入っていた訳ではなかった。総会に対して初めて公然と反対を表明した1人が、ロジャー・ウィリアムズという若い牧師であった。彼は植民地がインディアンの土地を没収したことに反対し、政教分離を主張した。また、アン・ハッチンソンという女性も、清教徒の神学理論の主要な原理に異議を唱えた。この2人は彼らの信奉者たちとともに追放された。

ウィリアムズは1636年に、ナラガンセット族のインディアンから土地を購入した。現在のロードアイランド州プロビデンス市である。1644年には、清教徒の支配する英国議会が彼を支持し、ロードアイランドに、完全な政教分離と宗教の自由を実現する植民地を創設する特許を与えた。

マサチューセッツを離れたのは、ウィリアムズのような、いわゆる「異端者」だけではなかった。間もなく正統派の清教徒も、より良い土地と機会を求めて、マサチューセッツ湾植民地を去り始めた。例えば、コネティカット川流域の肥沃な土地の噂が、やせた土地の農耕に苦心していた農民の関心を引いた。1630年代初めまでには、多くの人々がインディアンによる襲撃の危険を冒しても、深く豊かな土壌と平らな土地を求めようとしていた。こうして作られた新しい共同体では、教会の信徒であることを投票の資格とする規則が廃止されることが多く、その結果、ますます大勢の男性に参政権が与えられることになった。

これと時を同じくして、新世界が提供してくれそうな土地と自由を求めて、ますます移民が増えるに従い、ニューハンプシャーとメーンの海岸沿いに、他の入植地が現われ始めたのである。

オランダの東インド会社に雇われたヘンリー・ハドソンは、1609年に、現在のニューヨーク市と彼の名前が付けられたハドソン川周辺の地域を、おそらく現在のニューヨーク州オルバニー市の北あたりまで探検した。その後もオランダ人がこの地域を航海して領有権の根拠を固め、初期の入植地を建設した。

そこから北にいたフランス人と同様、オランダ人も当初は毛皮貿易に関心があった。そのために、彼らは毛皮産地の中心部で力を持っていたイロクォイ5部族との間に密接な関係を築いた。1617年、オランダ人入植者はハドソン川とモホーク川の交わる地点、現在のオルバニー市に砦を構築した。

マンハッタン島への入植は1620年代初めに始まった。1624年に同島は、地元のアメリカ先住民から買収された。買収価格は24ドルであったそうである。この島は直ちに「ニューアムステルダム」と改名された。

ハドソン川流域に入植者を誘致するために、オランダ人は「パトルーン制度(荘園地主制度)」と呼ばれる一種の封建貴族制度を奨励した。1630年に巨大な領地の第1号がハドソン川沿いに建設された。パトルーン制度の下では、株主である荘園地主、すなわちパトルーンは4年間で50人の成人を領地に連れてくる代わりに、同川沿いの25マイルに及ぶ土地を与えられ、漁業と狩猟の専有権、およびその土地の民事・刑事裁判権を与えられた。その見返りとしてパトルーンは、家畜、道具、および建物を提供した。借地人はパトルーンに借地料を払い、余剰作物の先買い権を与えた。

その3年後、さらに南ではオランダと提携していたスウェーデンの貿易会社がデラウェア川沿いに初の植民地を築き始めた。しかし、この植民地「ニュースウェーデン」は独自の地位を固めるだけの資源がなく、徐々にニューネーデルランドに吸収され、後にはペンシルベニアおよびデラウェアに吸収された。

1632年、カトリック教徒のカルバート家が、ポトマック川の北、後のメリーランド州に入植するための特許状を英国王チャールズ1世から与えられた。この特許状は、プロテスタント以外の教会の設立をはっきりと禁止していなかったため、この入植地はカトリック教徒の避難場所となった。1634年、ポトマック川がチェサピーク湾に流れ込む地点の近くに、メリーランドの最初の町セントメリーズが創設された。

カルバート家は、英国国教会の支配する英国でますます迫害されるようになっていたカトリック教徒のための避難場所を確立する一方で、利益を生む領地の建設にも関心があった。そのために、そしてまた英国政府との間の問題を避けるために、カルバート家はプロテスタントの移民も奨励した。

メリーランドの特許状には、封建的な要素と近代的な要素が入り混じっていた。カルバート家は荘園を建設する権限を持つ一方で、自由民(土地所有者)の同意を得なければ法律を作成することはできなかった。彼らは入植者を誘致し、その借地から利益を得るためには単なる荘園の小作地ではなく、農地を入植者に提供しなければならなかった。その結果として、独立した農場の数が増え、その所有者たちは入植地における発言権を要求した。メリーランドでは、1635年に初の議会が開かれた。

1640年までに英国は、ニューイングランド沿岸とチェサピーク湾の沿岸に植民地を確立した。その2カ所の間には、オランダ人の共同体とスウェーデン人の小さな共同体があった。そして西方には、アメリカ先住民が住んでいた。彼らは当時、「インディアン」と呼ばれた。

北米大陸東部のインディアン部族はヨーロッパ人にとって、時に友好的、時に敵対的な存在だったが、もはや見知らぬ他人とは言えなかった。アメリカ先住民は、新しい技術や貿易による恩恵を受けたが、初期の入植者がもたらした疾病や彼らの土地所有欲は、長い間培った生活様式にとっては深刻な問題でもあった。

当初、ヨーロッパ人入植者との交易は、ナイフ、斧、武器、調理用具、釣り針、その他多くの物品を入手し恩恵をもたらした。最初に入植者と交易を行ったインディアン部族は、そうでない部族に比べ、大きく優位に立つことができた。ヨーロッパ人の要求に応えてイロクォイなどの部族は、17世紀に毛皮猟に力を入れるようになった。18世紀の後半に至るまで、毛皮や生皮はインディアンの部族にとって、入植者から物品を購入する手段となった。

初期の植民地時代における入植者とアメリカ先住民との関係は、協力と対立の入り混じる不安定なものだった。ペンシルベニア植民地が作られてから最初の半世紀間に見られたような模範的な関係があった一方で、長期にわたって関係の悪化、小競り合い、そして戦争が連続的に発生した。その場合には、いつも決まってインディアンが敗北して、さらに土地を失っていった。

アメリカ先住民による初期の重要な反乱のひとつは、1622年にバージニアで発生した。この反乱では、ジェームズタウンに到着したばかりの多数の宣教師を含む白人347人が殺害された。

コネティカット川流域への白人入植がきっかけとなって、1637年にピーコット戦争が発生した。1675年には、1621年にピルグリムと最初に和平を結んだ族長の息子であるフィリップ王が、ニューイングランド南部の各部族を団結させて、ヨーロッパ人による土地囲い込みを食い止めようとした。しかし、その戦いでフィリップ王は死亡し、多くのインディアンが奴隷として売られた。

東部の未開拓地へ入植者が続々と流入したため、アメリカ先住民の生活は混乱した。多くの獲物が殺されて絶滅していくに従い、先住民は飢えるか、戦うか、あるいは西へ移動して他の部族と対立するか、という困難な選択を迫られた。

オンタリオ湖とエリー湖の南の地域のニューヨーク北部とペンシルベニアに住んでいたイロクォイ族は、ヨーロッパ人の進出の阻止に成功した。1570年、5つの部族が結束して「イロクォイ5族連合(Ho De No Sau Nee)」を形成した。これは、当時のアメリカ先住民の国家としては最も複雑な形態を持っていた。イロクォイ連合は加盟5部族の代表50人から成る評議会によって運営された。この評議会は、全ての部族に共通する問題を処理したが、各部族は自由かつ平等であり、評議会は各部族の日常業務に関しては決定権を持たなかった。どの部族にも独自に戦争を起こすことは許さなかった。評議会は殺人などの犯罪に対処する法律を可決した。

イロクォイ連合は1600年代および1700年代を通じて強力な存在だった。連合は、英国人と毛皮の交易を行い、米国の支配をめぐる1754年から1763年までの戦争に際して、英国を支援してフランスと戦った。イロクォイの協力がなければ、英国はこの戦争に勝てなかったかもしれない。

イロクォイ連合はアメリカ独立戦争まで、その力を維持していた。しかし、独立戦争の際に、どちらを支援するかを巡って同連合の評議会は初めて全員一致の結論に達することができなった。加盟部族はそれぞれ独自の決断を下し、英国とともに戦う部族、入植者とともに戦う部族、そして中立を保つ部族に分かれた。その結果、どの部族もほかの部族と戦うことになった。イロクォイ連合は多大な損失を被り、2度と回復することができなかった。

17世紀半ばの英国では宗教紛争や内戦によって、移民が減少するとともに、米国の新しい植民地に対する母国としての関心も薄れた。

ひとつには、英国が防衛措置を疎かにしていたことへの対策として、マサチューセッツ湾、プリマス、コネティカット、ニューヘーブンの各植民地が1643年に、ニューイングランド連合を結成した。これは欧州からの入植者による初の地域的な統合の試みだった。

英国人入植者の初期の歴史を見ると、様々なグループが内部でも、あるいは近隣同士でも地位と権力を求めて競い合い、宗教的、政治的にかなりの対立があったことがわかる。特にメリーランド植民地は、オリバー・クロムウェルの時代の英国における激しい宗教的対立の影響を受けた。そうした対立の犠牲になったのが、同植民地の宗教寛容法(1649年)で、1650年代に廃止されてしまった。しかし同法は、宗教の自由を保障する条項とともに、間もなく復活している。

英国は、1660年のチャールズ2世の王政復古とともに、再び北米へ関心を向けるようになり、短期間のうちにカロライナに初のヨーロッパ人植民地が建設され、オランダがニューネーデルランドから追い出された。新しい独占植民地が、ニューヨーク、ニュージャージー、デラウェア、ペンシルベニアに建設された。

オランダ人の入植地は欧州で任命された専制的な総督によって統治されていた。時とともに入植者たちは、これらの総督とは疎遠になっていった。その結果、英国人入植者がロングアイランドとマンハッタンで、オランダ領地を侵食し始めたときに、人気のない総督は、防衛のために人々を結集させることができなかった。こうして、ニューネーデルランドは1664年に陥落した。しかしながら、降伏の条件は緩やかなものであり、オランダ人入植者は所有地を保持するとともに、礼拝の自由も保つことができた。

1650年代にはすでに、現在のノースカロライナ州北部沿岸のアルバマール湾周辺にバージニアから下ってきた入植者が住んでいた。1664年には最初の総督が到着した。アルバマール地域は今でも人里離れているが、ここに最初の町ができたのは、1704年にフランスのユグノー教徒が渡ってきてからのことである。

1670年には、ニューイングランドとカリブ海のバルバドス島から現在のサウスカロライナ州チャールストン市に、初めの入植者が到着した。この新しい植民地には、英国の哲学者ジョン・ロックが策定に貢献した複雑な統治制度が用意されていた。その大きな特徴のひとつは、世襲の貴族制を取り入れようとする試みが失敗に終わったことである。この植民地の最も好ましくない側面のひとつは、初期にインディアン奴隷の取引が行われたことである。しかし、時とともに、材木、コメ、藍などの産物によって、より価値のある経済基盤が築かれていった。

1681年に、裕福なクエーカー教徒で英国王チャールズ2世の友人であったウィリアム・ペンが、デラウェア川の西の広大な土地を与えられ、これがペンシルベニアと呼ばれるようになった。ペンは英国と欧州大陸から、ペンシルベニアの人口を増やすために、クエーカー、メノナイト、アーミッシュ、モラビアン、バプテストなど、様々な非国教徒を積極的に誘致した。

翌年、ペンが到着したころには、すでにデラウェア川沿いに、オランダ人、スウェーデン人、英国人の入植者が住んでいた。ペンは、その地に「兄弟愛の町」を意味する「フィラデルフィア」を創設した。

ペンは自分の信仰に忠実に、当時のアメリカの植民地ではあまり見られなかったような平等意識に刺激を受けていた。したがって、ペンシルベニアでは、米国内の他地域に比べ、かなり早くから女性に権利が与えられていた。また、ペンとその副官たちは、デラウェア・インディアンとの関係も重視し、ヨーロッパ人が入植した土地については、必ずインディアンに代価が支払われるようにした。

1732年にジョージアが入植され、13番目の植民地となった。スペイン領のフロリダに囲まれてはいないものの、そこに隣接するジョージアはスペインの侵略に対する緩衝地帯と見なされていた。しかし、ジョージアには、もうひとつの特徴があった。ジョージアの要塞化の責任者となったジェームズ・オグルソープ将軍は、改革主義者であり、貧しい人々や元囚人に新たな機会を与える避難場所を意図的に作り出そうとした。

米国での新しい生活に積極的に関心を払わなかった人々も、しばしば勧誘者の巧妙な説得に乗せられて新世界に移住してきた。例えば、ウィリアム・ペンは、ペンシルベニア植民地へ移住する者を待っている好機について宣伝した。また、裁判官や刑務所の責任者は、有罪判決を受けた者に服役する代わりにジョージアのような植民地へ移住する機会を与えた。

しかし、新世界で新しい生活を始めるために、自分や家族の旅費を支払える入植者は少なかった。船長が、契約奉公人と呼ばれる貧しい移住者の労働契約を売って多額の報酬を得ることもあった。そして、船にできるだけ多くの移住者を乗せるために、法外な約束から実際の誘拐まで、あらゆる手段が使われた。

バージニア会社やマサチューセッツ湾会社のように、植民会社が入植者の旅費と維持費を負担することもあった。その代わりに、入植者は通常4~7年間、会社のために契約奉公人として働くことを約束した。その期間が終了すると、彼らは自由になり「自由手当て」を与えられた。これには小さな土地が含まれることもあった。

ニューイングランドより南にある植民地に住んでいた入植者の、おそらく半数は、こうした制度の下で米国へやって来た人たちであった。彼らのほとんどは忠実に義務を果たしたが、雇い主の元から脱走する者もいた。それでも最終的には、彼らの多くは最初に移住した植民地か近隣の植民地で、土地を確保し、家を持つことができた。このような半拘束制度の下で米国へ来た一族に対して社会的な偏見はなかった。どの植民地にも、それぞれ年季奉公人出身の指導者がいた。

ただし、ひとつだけ極めて重要な例外があった。それはアフリカ人奴隷である。アフリカの黒人が初めてバージニアに連れて来られたのは、ジェームズタウン創設からわずか12年後の1619年のことだった。当初、彼らの多くは、いずれ自由を得ることのできる年季奉公人と見なされていた。しかし、南部の植民地の大農園で働く労働者の需要が増えるに伴い、1660年代までに、彼らを取り囲む奴隷制度に、徐々に固く縛られるようになった。アフリカ人は、一生強制労働をさせられるために、手かせ足かせをはめられて米国に連れて来られるようになった。

|

Early America

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication Outline of U.S. History.)

"Heaven and Earth never agreed better to frame a place for man's habitation."

– Jamestown founder John Smith, 1607

THE FIRST AMERICANS

At the height of the Ice Age, between 34,000 and 30,000 B.C., much of the world's water was locked up in vast continental ice sheets. As a result, the Bering Sea was hundreds of meters below its current level, and a land bridge, known as Beringia, emerged between Asia and North America. At its peak, Beringia is thought to have been some 1,500 kilometers wide. A moist and treeless tundra, it was covered with grasses and plant life, attracting the large animals that early humans hunted for their survival.

The first people to reach North America almost certainly did so without knowing they had crossed into a new continent. They would have been following game, as their ancestors had for thousands of years, along the Siberian coast and then across the land bridge.

Once in Alaska, it would take these first North Americans thousands of years more to work their way through the openings in great glaciers south to what is now the United States. Evidence of early life in North America continues to be found. Little of it, however, can be reliably dated before 12,000 B.C.; a recent discovery of a hunting lookout in northern Alaska, for example, may date from almost that time. So too may the finely crafted spear points and items found near Clovis, New Mexico.

Similar artifacts have been found at sites throughout North and South America, indicating that life was probably already well established in much of the Western Hemisphere by some time prior to 10,000 B.C.

Around that time the mammoth began to die out and the bison took its place as a principal source of food and hides for these early North Americans. Over time, as more and more species of large game vanished – whether from overhunting or natural causes – plants, berries, and seeds became an increasingly important part of the early American diet. Gradually, foraging and the first attempts at primitive agriculture appeared. Native Americans in what is now central Mexico led the way, cultivating corn, squash, and beans, perhaps as early as 8,000 B.C. Slowly, this knowledge spread northward.

By 3,000 B.C., a primitive type of corn was being grown in the river valleys of New Mexico and Arizona. Then the first signs of irrigation began to appear, and, by 300 B.C., signs of early village life.

By the first centuries A.D., the Hohokam were living in settlements near what is now Phoenix, Arizona, where they built ball courts and pyramid – like mounds reminiscent of those found in Mexico, as well as a canal and irrigation system.

MOUND BUILDERS AND PUEBLOS

The first Native-American group to build mounds in what is now the United States often are called the Adenans. They began constructing earthen burial sites and fortifications around 600 B.C. Some mounds from that era are in the shape of birds or serpents; they probably served religious purposes not yet fully understood.

The Adenans appear to have been absorbed or displaced by various groups collectively known as Hopewellians. One of the most important centers of their culture was found in southern Ohio, where the remains of several thousand of these mounds still can be seen. Believed to be great traders, the Hopewellians used and exchanged tools and materials across a wide region of hundreds of kilometers.

By around 500 A.D., the Hopewellians disappeared, too, gradually giving way to a broad group of tribes generally known as the Mississippians or Temple Mound culture. One city, Cahokia, near Collinsville , Illinois, is thought to have had a population of about 20,000 at its peak in the early 12th century. At the center of the city stood a huge earthen mound, flattened at the top, that was 30 meters high and 37 hectares at the base. Eighty other mounds have been found nearby.

Cities such as Cahokia depended on a combination of hunting, foraging, trading, and agriculture for their food and supplies. Influenced by the thriving societies to the south, they evolved into complex hierarchical societies that took slaves and practiced human sacrifice.

In what is now the southwest United States, the Anasazi, ancestors of the modern Hopi Indians, began building stone and adobe pueblos around the year 900. These unique and amazing apartment – like structures were often built along cliff faces; the most famous, the "cliff palace" of Mesa Verde, Colorado, had more than 200 rooms. Another site, the Pueblo Bonito ruins along New Mexico's Chaco River, once contained more than 800 rooms.

Perhaps the most affluent of the pre-Columbian Native Americans lived in the Pacific Northwest, where the natural abundance of fish and raw materials made food supplies plentiful and permanent villages possible as early as 1,000 B.C. The opulence of their "potlatch" gatherings remains a standard for extravagance and festivity probably unmatched in early American history.

NATIVE-AMERICAN CULTURES

The America that greeted the first Europeans was, thus, far from an empty wilderness. It is now thought that as many people lived in the Western Hemisphere as in Western Europe at that time – about 40 million. Estimates of the number of Native Americans living in what is now the United States at the onset of European colonization range from two to 18 million, with most historians tending toward the lower figure. What is certain is the devastating effect that European disease had on the indigenous population practically from the time of initial contact. Smallpox, in particular, ravaged whole communities and is thought to have been a much more direct cause of the precipitous decline in the Indian population in the 1600s than the numerous wars and skirmishes with European settlers.

Indian customs and culture at the time were extraordinarily diverse, as could be expected, given the expanse of the land and the many different environments to which they had adapted. Some generalizations, however, are possible. Most tribes, particularly in the wooded eastern region and the Midwest, combined aspects of hunting, gathering, and the cultivation of maize and other products for their food supplies. In many cases, the women were responsible for farming and the distribution of food, while the men hunted and participated in war.

By all accounts, Native-American society in North America was closely tied to the land. Identification with nature and the elements was integral to religious beliefs. Their life was essentially clan – oriented and communal, with children allowed more freedom and tolerance than was the European custom of the day.

Although some North American tribes developed a type of hieroglyphics to preserve certain texts, Native-American culture was primarily oral, with a high value placed on the recounting of tales and dreams. Clearly, there was a good deal of trade among various groups and strong evidence exists that neighboring tribes maintained extensive and formal relations – both friendly and hostile.

THE FIRST EUROPEANS

The first Europeans to arrive in North America – at least the first for whom there is solid evidence – were Norse, traveling west from Greenland, where Erik the Red had founded a settlement around the year 985. In 1001 his son Leif is thought to have explored the northeast coast of what is now Canada and spent at least one winter there.

While Norse sagas suggest that Viking sailors explored the Atlantic coast of North America down as far as the Bahamas, such claims remain unproven. In 1963, however, the ruins of some Norse houses dating from that era were discovered at L'Anse-aux-Meadows in northern Newfoundland, thus supporting at least some of the saga claims.

In 1497, just five years after Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean looking for a western route to Asia, a Venetian sailor named John Cabot arrived in Newfoundland on a mission for the British king. Although quickly forgotten, Cabot's journey was later to provide the basis for British claims to North America. It also opened the way to the rich fishing grounds off George's Banks, to which European fishermen, particularly the Portuguese, were soon making regular visits.

Columbus never saw the mainland of the future United States, but the first explorations of it were launched from the Spanish possessions that he helped establish. The first of these took place in 1513 when a group of men under Juan Ponce de León landed on the Florida coast near the present city of St. Augustine.

With the conquest of Mexico in 1522, the Spanish further solidified their position in the Western Hemisphere. The ensuing discoveries added to Europe's knowledge of what was now named America – after the Italian Amerigo Vespucci, who wrote a widely popular account of his voyages to a "New World." By 1529 reliable maps of the Atlantic coastline from Labrador to Tierra del Fuego had been drawn up, although it would take more than another century before hope of discovering a "Northwest Passage" to Asia would be completely abandoned.

Among the most significant early Spanish explorations was that of Hernando De Soto, a veteran conquistador who had accompanied Francisco Pizarro in the conquest of Peru. Leaving Havana in 1539, De Soto's expedition landed in Florida and ranged through the southeastern United States as far as the Mississippi River in search of riches.

Another Spaniard, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, set out from Mexico in 1540 in search of the mythical Seven Cities of Cibola. Coronado's travels took him to the Grand Canyon and Kansas, but failed to reveal the gold or treasure his men sought. However, his party did leave the peoples of the region a remarkable, if unintended, gift: Enough of his horses escaped to transform life on the Great Plains. Within a few generations, the Plains Indians had become masters of horsemanship, greatly expanding the range and scope of their activities.

While the Spanish were pushing up from the south, the northern portion of the present – day United States was slowly being revealed through the journeys of men such as Giovanni da Verrazano. A Florentine who sailed for the French, Verrazano made landfall in North Carolina in 1524, then sailed north along the Atlantic Coast past what is now New York harbor.

A decade later, the Frenchman Jacques Cartier set sail with the hope – like the other Europeans before him – of finding a sea passage to Asia. Cartier's expeditions along the St. Lawrence River laid the foundation for the French claims to North America, which were to last until 1763.

Following the collapse of their first Quebec colony in the 1540s, French Huguenots attempted to settle the northern coast of Florida two decades later. The Spanish, viewing the French as a threat to their trade route along the Gulf Stream, destroyed the colony in 1565. Ironically, the leader of the Spanish forces, Pedro Menéndez, would soon establish a town not far away – St. Augustine. It was the first permanent European settlement in what would become the United States.

The great wealth that poured into Spain from the colonies in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Peru provoked great interest on the part of the other European powers. Emerging maritime nations such as England, drawn in part by Francis Drake's successful raids on Spanish treasure ships, began to take an interest in the New World.

In 1578 Humphrey Gilbert, the author of a treatise on the search for the Northwest Passage, received a patent from Queen Elizabeth to colonize the "heathen and barbarous landes" in the New World that other European nations had not yet claimed. It would be five years before his efforts could begin. When he was lost at sea, his half‑brother, Walter Raleigh, took up the mission.

In 1585 Raleigh established the first British colony in North America, on Roanoke Island off the coast of North Carolina. It was later abandoned, and a second effort two years later also proved a failure. It would be 20 years before the British would try again. This time – at Jamestown in 1607 – the colony would succeed, and North America would enter a new era.

EARLY SETTLEMENTS

The early 1600s saw the beginning of a great tide of emigration from Europe to North America. Spanning more than three centuries, this movement grew from a trickle of a few hundred English colonists to a flood of millions of newcomers. Impelled by powerful and diverse motivations, they built a new civilization on the northern part of the continent.

The first English immigrants to what is now the United States crossed the Atlantic long after thriving Spanish colonies had been established in Mexico, the West Indies, and South America. Like all early travelers to the New World, they came in small, overcrowded ships. During their six-to 12-week voyages, they lived on meager rations. Many died of disease, ships were often battered by storms, and some were lost at sea.

Most European emigrants left their homelands to escape political oppression, to seek the freedom to practice their religion, or to find opportunities denied them at home. Between 1620 and 1635, economic difficulties swept England. Many people could not find work. Even skilled artisans could earn little more than a bare living. Poor crop yields added to the distress. In addition, the Commercial Revolution had created a burgeoning textile industry, which demanded an ever-increasing supply of wool to keep the looms running. Landlords enclosed farmlands and evicted the peasants in favor of sheep cultivation. Colonial expansion became an outlet for this displaced peasant population.

The colonists' first glimpse of the new land was a vista of dense woods. The settlers might not have survived had it not been for the help of friendly Indians, who taught them how to grow native plants – pumpkin, squash, beans, and corn. In addition, the vast, virgin forests, extending nearly 2,100 kilometers along the Eastern seaboard, proved a rich source of game and firewood. They also provided abundant raw materials used to build houses, furniture, ships, and profitable items for export.

Although the new continent was remarkably endowed by nature, trade with Europe was vital for articles the settlers could not produce. The coast served the immigrants well. The whole length of shore provided many inlets and harbors. Only two areas – North Carolina and southern New Jersey – lacked harbors for ocean-going vessels.

Majestic rivers – the Kennebec, Hudson, Delaware, Susquehanna, Potomac, and numerous others – linked lands between the coast and the Appalachian Mountains with the sea. Only one river, however, the St. Lawrence – dominated by the French in Canada – offered a water passage to the Great Lakes and the heart of the continent. Dense forests, the resistance of some Indian tribes, and the formidable barrier of the Appalachian Mountains discouraged settlement beyond the coastal plain. Only trappers and traders ventured into the wilderness. For the first hundred years the colonists built their settlements compactly along the coast.

Political considerations influenced many people to move to America. In the 1630s, arbitrary rule by England's Charles I gave impetus to the migration. The subsequent revolt and triumph of Charles' opponents under Oliver Cromwell in the 1640s led many cavaliers – "king's men" – to cast their lot in Virginia. In the German-speaking regions of Europe, the oppressive policies of various petty princes – particularly with regard to religion – and the devastation caused by a long series of wars helped swell the movement to America in the late 17th and 18th centuries.

The journey entailed careful planning and management, as well as considerable expense and risk. Settlers had to be transported nearly 5,000 kilometers across the sea. They needed utensils, clothing, seed, tools, building materials, livestock, arms, and ammunition. In contrast to the colonization policies of other countries and other periods, the emigration from England was not directly sponsored by the government but by private groups of individuals whose chief motive was profit.

JAMESTOWN

The first of the British colonies to take hold in North America was Jamestown. On the basis of a charter which King James I granted to the Virginia (or London) company, a group of about 100 men set out for the Chesapeake Bay in 1607. Seeking to avoid conflict with the Spanish, they chose a site about 60 kilometers up the James River from the bay.

Made up of townsmen and adventurers more interested in finding gold than farming, the group was unequipped by temperament or ability to embark upon a completely new life in the wilderness. Among them, Captain John Smith emerged as the dominant figure. Despite quarrels, starvation, and Native-American attacks, his ability to enforce discipline held the little colony together through its first year.

In 1609 Smith returned to England, and in his absence, the colony descended into anarchy. During the winter of 1609-1610, the majority of the colonists succumbed to disease. Only 60 of the original 300 settlers were still alive by May 1610. That same year, the town of Henrico (now Richmond) was established farther up the James River.

It was not long, however, before a development occurred that revolutionized Virginia's economy. In 1612 John Rolfe began cross‑breeding imported tobacco seed from the West Indies with native plants and produced a new variety that was pleasing to European taste. The first shipment of this tobacco reached London in 1614. Within a decade it had become Virginia's chief source of revenue.

Prosperity did not come quickly, however, and the death rate from disease and Indian attacks remained extraordinarily high. Between 1607 and 1624 approximately 14,000 people migrated to the colony, yet only 1,132 were living there in 1624. On recommendation of a royal commission, the king dissolved the Virginia Company, and made it a royal colony that year.

MASSACHUSETTS

During the religious upheavals of the 16th century, a body of men and women called Puritans sought to reform the Established Church of England from within. Essentially, they demanded that the rituals and structures associated with Roman Catholicism be replaced by simpler Calvinist Protestant forms of faith and worship. Their reformist ideas, by destroying the unity of the state church, threatened to divide the people and to undermine royal authority.

In 1607 a small group of Separatists – a radical sect of Puritans who did not believe the Established Church could ever be reformed – departed for Leyden, Holland, where the Dutch granted them asylum. However, the Calvinist Dutch restricted them mainly to low-paid laboring jobs. Some members of the congregation grew dissatisfied with this discrimination and resolved to emigrate to the New World.

In 1620, a group of Leyden Puritans secured a land patent from the Virginia Company. Numbering 101, they set out for Virginia on the Mayflower. A storm sent them far north and they landed in New England on Cape Cod. Believing themselves outside the jurisdiction of any organized government, the men drafted a formal agreement to abide by "just and equal laws" drafted by leaders of their own choosing. This was the Mayflower Compact.

In December the Mayflower reached Plymouth harbor; the Pilgrims began to build their settlement during the winter. Nearly half the colonists died of exposure and disease, but neighboring Wampanoag Indians provided the information that would sustain them: how to grow maize. By the next fall, the Pilgrims had a plentiful crop of corn, and a growing trade based on furs and lumber.

A new wave of immigrants arrived on the shores of Massachusetts Bay in 1630 bearing a grant from King Charles I to establish a colony. Many of them were Puritans whose religious practices were increasingly prohibited in England. Their leader, John Winthrop, urged them to create a "city upon a hill" in the New World – a place where they would live in strict accordance with their religious beliefs and set an example for all of Christendom.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was to play a significant role in the development of the entire New England region, in part because Winthrop and his Puritan colleagues were able to bring their charter with them. Thus the authority for the colony's government resided in Massachusetts, not in England.

Under the charter's provisions, power rested with the General Court, which was made up of "freemen" required to be members of the Puritan, or Congregational, Church. This guaranteed that the Puritans would be the dominant political as well as religious force in the colony. The General Court elected the governor, who for most of the next generation would be John Winthrop.

The rigid orthodoxy of the Puritan rule was not to everyone's liking. One of the first to challenge the General Court openly was a young clergyman named Roger Williams, who objected to the colony's seizure of Indian lands and advocated separation of church and state. Another dissenter, Anne Hutchinson, challenged key doctrines of Puritan theology. Both they and their followers were banished.

Williams purchased land from the Narragansett Indians in what is now Providence, Rhode Island, in 1636. In 1644, a sympathetic Puritan-controlled English Parliament gave him the charter that established Rhode Island as a distinct colony where complete separation of church and state as well as freedom of religion was practiced.

So‑called heretics like Williams were not the only ones who left Massachusetts. Orthodox Puritans, seeking better lands and opportunities, soon began leaving Massachusetts Bay Colony. News of the fertility of the Connecticut River Valley, for instance, attracted the interest of farmers having a difficult time with poor land. By the early 1630s, many were ready to brave the danger of Indian attack to obtain level ground and deep, rich soil. These new communities often eliminated church membership as a prerequisite for voting, thereby extending the franchise to ever larger numbers of men.

At the same time, other settlements began cropping up along the New Hampshire and Maine coasts, as more and more immigrants sought the land and liberty the New World seemed to offer.

NEW NETHERLAND AND MARYLAND

Hired by the Dutch East India Company, Henry Hudson in 1609 explored the area around what is now New York City and the river that bears his name, to a point probably north of present-day Albany, New York. Subsequent Dutch voyages laid the basis for their claims and early settlements in the area.

As with the French to the north, the first interest of the Dutch was the fur trade. To this end, they cultivated close relations with the Five Nations of the Iroquois, who were the key to the heartland from which the furs came. In 1617 Dutch settlers built a fort at the junction of the Hudson and the Mohawk Rivers, where Albany now stands.

Settlement on the island of Manhattan began in the early 1620s. In 1624, the island was purchased from local Native Americans for the reported price of $24. It was promptly renamed New Amsterdam.

In order to attract settlers to the Hudson River region, the Dutch encouraged a type of feudal aristocracy, known as the "patroon" system. The first of these huge estates were established in 1630 along the Hudson River. Under the patroon system, any stockholder, or patroon, who could bring 50 adults to his estate over a four-year period was given a 25-kilometer river-front plot, exclusive fishing and hunting privileges, and civil and criminal jurisdiction over his lands. In turn, he provided livestock, tools, and buildings. The tenants paid the patroon rent and gave him first option on surplus crops.

Further to the south, a Swedish trading company with ties to the Dutch attempted to set up its first settlement along the Delaware River three years later. Without the resources to consolidate its position, New Sweden was gradually absorbed into New Netherland, and later, Pennsylvania and Delaware.

In 1632 the Catholic Calvert family obtained a charter for land north of the Potomac River from King Charles I in what became known as Maryland. As the charter did not expressly prohibit the establishment of non-Protestant churches, the colony became a haven for Catholics. Maryland's first town, St. Mary's, was established in 1634 near where the Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay.

While establishing a refuge for Catholics, who faced increasing persecution in Anglican England, the Calverts were also interested in creating profitable estates. To this end, and to avoid trouble with the British government, they also encouraged Protestant immigration.

Maryland’s royal charter had a mixture of feudal and modern elements. On the one hand the Calvert family had the power to create manorial estates. On the other, they could only make laws with the consent of freemen (property holders). They found that in order to attract settlers – and make a profit from their holdings – they had to offer people farms, not just tenancy on manorial estates. The number of independent farms grew in consequence. Their owners demanded a voice in the affairs of the colony. Maryland's first legislature met in 1635.

COLONIAL-INDIAN RELATIONS

By 1640 the British had solid colonies established along the New England coast and the Chesapeake Bay. In between were the Dutch and the tiny Swedish community. To the west were the original Americans, then called Indians.

Sometimes friendly, sometimes hostile, the Eastern tribes were no longer strangers to the Europeans. Although Native Americans benefited from access to new technology and trade, the disease and thirst for land that the early settlers also brought posed a serious challenge to their long-established way of life.

At first, trade with the European settlers brought advantages: knives, axes, weapons, cooking utensils, fishhooks, and a host of other goods. Those Indians who traded initially had significant advantage over rivals who did not. In response to European demand, tribes such as the Iroquois began to devote more attention to fur trapping during the 17th century. Furs and pelts provided tribes the means to purchase colonial goods until late into the 18th century.

Early colonial-Native-American relations were an uneasy mix of cooperation and conflict. On the one hand, there were the exemplary relations that prevailed during the first half century of Pennsylvania's existence. On the other were a long series of setbacks, skirmishes, and wars, which almost invariably resulted in an Indian defeat and further loss of land.

The first of the important Native-American uprisings occurred in Virginia in 1622, when some 347 whites were killed, including a number of missionaries who had just recently come to Jamestown.

White settlement of the Connecticut River region touched off the Pequot War in 1637. In 1675 King Philip, the son of the native chief who had made the original peace with the Pilgrims in 1621, attempted to unite the tribes of southern New England against further European encroachment of their lands. In the struggle, however, Philip lost his life and many Indians were sold into servitude.

The steady influx of settlers into the backwoods regions of the Eastern colonies disrupted Native-American life. As more and more game was killed off, tribes were faced with the difficult choice of going hungry, going to war, or moving and coming into conflict with other tribes to the west.

The Iroquois, who inhabited the area below lakes Ontario and Erie in northern New York and Pennsylvania, were more successful in resisting European advances. In 1570 five tribes joined to form the most complex Native-American nation of its time, the "Ho-De-No-Sau-Nee," or League of the Iroquois. The league was run by a council made up of 50 representatives from each of the five member tribes. The council dealt with matters common to all the tribes, but it had no say in how the free and equal tribes ran their day-to-day affairs. No tribe was allowed to make war by itself. The council passed laws to deal with crimes such as murder.

The Iroquois League was a strong power in the 1600s and 1700s. It traded furs with the British and sided with them against the French in the war for the dominance of America between 1754 and 1763. The British might not have won that war otherwise.

The Iroquois League stayed strong until the American Revolution. Then, for the first time, the council could not reach a unanimous decision on whom to support. Member tribes made their own decisions, some fighting with the British, some with the colonists, some remaining neutral. As a result, everyone fought against the Iroquois. Their losses were great and the league never recovered.

SECOND GENERATION OF BRITISH COLONIES

The religious and civil conflict in England in the mid-17th century limited immigration, as well as the attention the mother country paid the fledgling American colonies.

In part to provide for the defense measures England was neglecting, the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven colonies formed the New England Confederation in 1643. It was the European colonists' first attempt at regional unity.

The early history of the British settlers reveals a good deal of contention – religious and political – as groups vied for power and position among themselves and their neighbors. Maryland, in particular, suffered from the bitter religious rivalries that afflicted England during the era of Oliver Cromwell. One of the casualties was the state's Toleration Act, which was revoked in the 1650s. It was soon reinstated, however, along with the religious freedom it guaranteed.

With the restoration of King Charles II in 1660, the British once again turned their attention to North America. Within a brief span, the first European settlements were established in the Carolinas and the Dutch driven out of New Netherland. New proprietary colonies were established in New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.

The Dutch settlements had been ruled by autocratic governors appointed in Europe. Over the years, the local population had become estranged from them. As a result, when the British colonists began encroaching on Dutch claims in Long Island and Manhattan, the unpopular governor was unable to rally the population to their defense. New Netherland fell in 1664. The terms of the capitulation, however, were mild: The Dutch settlers were able to retain their property and worship as they pleased.

As early as the 1650s, the Albemarle Sound region off the coast of what is now northern North Carolina was inhabited by settlers trickling down from Virginia. The first proprietary governor arrived in 1664. The first town in Albemarle, a remote area even today, was not established until the arrival of a group of French Huguenots in 1704.

In 1670 the first settlers, drawn from New England and the Caribbean island of Barbados, arrived in what is now Charleston, South Carolina. An elaborate system of government, to which the British philosopher John Locke contributed, was prepared for the new colony. One of its prominent features was a failed attempt to create a hereditary nobility. One of the colony's least appealing aspects was the early trade in Indian slaves. With time, however, timber, rice, and indigo gave the colony a worthier economic base.

In 1681 William Penn, a wealthy Quaker and friend of Charles II, received a large tract of land west of the Delaware River, which became known as Pennsylvania. To help populate it, Penn actively recruited a host of religious dissenters from England and the continent – Quakers, Mennonites, Amish, Moravians, and Baptists.

When Penn arrived the following year, there were already Dutch, Swedish, and English settlers living along the Delaware River. It was there he founded Philadelphia, the "City of Brotherly Love."

In keeping with his faith, Penn was motivated by a sense of equality not often found in other American colonies at the time. Thus, women in Pennsylvania had rights long before they did in other parts of America. Penn and his deputies also paid considerable attention to the colony's relations with the Delaware Indians, ensuring that they were paid for land on which the Europeans settled.

Georgia was settled in 1732, the last of the 13 colonies to be established. Lying close to, if not actually inside the boundaries of Spanish Florida, the region was viewed as a buffer against Spanish incursion. But it had another unique quality: The man charged with Georgia's fortifications, General James Oglethorpe, was a reformer who deliberately set out to create a refuge where the poor and former prisoners would be given new opportunities.

SETTLERS, SLAVES, AND SERVANTS

Men and women with little active interest in a new life in America were often induced to make the move to the New World by the skillful persuasion of promoters. William Penn, for example, publicized the opportunities awaiting newcomers to the Pennsylvania colony. Judges and prison authorities offered convicts a chance to migrate to colonies like Georgia instead of serving prison sentences.

But few colonists could finance the cost of passage for themselves and their families to make a start in the new land. In some cases, ships' captains received large rewards from the sale of service contracts for poor migrants, called indentured servants, and every method from extravagant promises to actual kidnapping was used to take on as many passengers as their vessels could hold.

In other cases, the expenses of transportation and maintenance were paid by colonizing agencies like the Virginia or Massachusetts Bay Companies. In return, indentured servants agreed to work for the agencies as contract laborers, usually for four to seven years. Free at the end of this term, they would be given "freedom dues," sometimes including a small tract of land.

Perhaps half the settlers living in the colonies south of New England came to America under this system. Although most of them fulfilled their obligations faithfully, some ran away from their employers. Nevertheless, many of them were eventually able to secure land and set up homesteads, either in the colonies in which they had originally settled or in neighboring ones. No social stigma was attached to a family that had its beginning in America under this semi-bondage. Every colony had its share of leaders who were former indentured servants.

There was one very important exception to this pattern: African slaves. The first black Africans were brought to Virginia in 1619, just 12 years after the founding of Jamestown. Initially, many were regarded as indentured servants who could earn their freedom. By the 1660s, however, as the demand for plantation labor in the Southern colonies grew, the institution of slavery began to harden around them, and Africans were brought to America in shackles for a lifetime of involuntary servitude.