国務省出版物

米国の歴史の概要 – 南北戦争と再建期

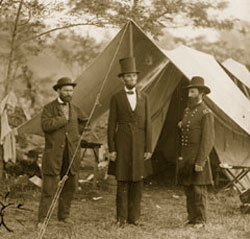

1862年10月、アンティータムの戦いのあとに、北軍の野営地を訪れたエイブラハム・リンカーン大統領(中央) (Library of Congress)

1860年11月の大統領選挙でリンカーンが勝利を収めたときから、12月20日のサウスカロライナ州の連邦脱退は既定の事実となっていた。サウスカロライナ州は、反奴隷制勢力に対して南部を団結させる出来事を長い間待っていたのである。1861年2月1日までには、さらに南部の5州が連邦を脱退した。2月8日に、この6州は、南部連合の暫定憲法に署名をした。残りの南部諸州はまだ連邦に属していたが、テキサス州は脱退に向けて動き始めていた。

それから1カ月もたたない1861年3月4日、エイブラハム・リンカーンが合衆国大統領に宣誓就任した。リンカーンは就任演説で、南部連合は「法的に無効」であると宣言した。演説の最後に、リンカーンは、連邦の統一回復を訴えたが、南部は聞く耳を持たなかった。4月12日、南部連合軍は、サウスカロライナ州チャールストン港のサムター要塞の連邦軍駐屯地を砲撃した。こうして、米国史上、後にも先にも最多の米国人戦死者を出すことになる戦争が始まったのである。

脱退した7州の人々は、南軍の行動と、南部連合のジェファソン・デービス大統領のリーダーシップを支持した。そして、南部も北部も、それまで連邦に従っていた奴隷州の出方を、かたずをのんで見守っていた。4月17日にバージニア州が脱退し、間もなくアーカンソー、テネシー、ノースカロライナの各州がこれに続いた。

連邦脱退を最もためらったのはバージニア州であった。同州の政治家たちは、アメリカ独立戦争の勝利と合衆国憲法の立案に指導的な役割を果たした人々であり、同州からは5人の合衆国大統領が出ていた。バージニア州の脱退とともに、同州出身のロバート・E・リー大佐は、バージニア州への忠誠のため、連邦軍の指揮を取ることを辞退した。

拡大した南部と、自由土地主義の北部との境界には、デラウェア、メリーランド、ケンタッキー、およびミズーリの各奴隷州があり、これらの州は、ある程度南部に同調しながらも、連邦に残った。

北軍も南軍も、開戦時には、早期の勝利を予想していた。物理的な資源においては、北部が明らかに有利であった。23州から成り、総人口2200万人の北部に対して、南部は11州、人口は奴隷を含め900万人であった。人口における優勢にも増して、北部は工業力で大きく優っており、武器・弾薬、衣服、およびその他の物資を製造する施設が豊富に存在した。また北部には、南部に比べ、はるかに充実した鉄道網があった。

しかしながら南部にも有利な点がいくつかあった。最も重要な利点は、地理的条件であった。すなわち、南部は、自らの領土内で防衛のために戦う立場にあった。彼らは、北軍を撃退するだけで、独立を得ることができた。また南部には、より強力な軍隊の伝統があり、より経験豊富な軍事指導者がそろっていた。

南北戦争の最初の大きな戦闘である、ワシントンに近いバージニア州ブルランでの戦い(第1次マナサスの戦いとも呼ばれる)により、迅速あるいは容易な勝利という幻想は跡形もなく消えた。またこの戦いは、少なくとも米国東部においては、南軍が大勢の死傷者を出して勝利を収めるが、それが南部連合にとって決定的な軍事的優勢には決してつながらない、というパターンを確立することになった。

北軍は、東部における敗北とは対照的に、西部での戦闘では勝利を収め、海上でも徐々に戦略を成功させていった。南北戦争初期には、海軍のほとんどは北軍の手中にあったが、各地に分散しており、弱体であった。ギディオン・ウェルズ海軍長官は、直ちに海軍強化の措置を取った。そしてリンカーンは、南部の海岸の封鎖を宣言した。初めは封鎖の効果はほとんどなかったが、1863年までには、ヨーロッパへの綿花輸出をほぼ完全に停止させ、南部がどうしても必要としていた軍需品、衣服、および医療品の輸入を阻むまでになっていた。

北軍の優秀な海軍提督デービッド・ファラガットは、2度にわたって目覚ましい作戦を展開した。1862年4月、彼の率いる艦隊がミシシッピ川の河口に入り、南部最大の都市であったルイジアナ州ニューオーリンズ市を攻略した。そして1864年8月には、「魚雷など気にするな。全速力で前進しろ」と命令して、アラバマ州モービル湾入り口の強力な防備を突破し、南軍の装甲艦を捕獲して、港を封鎖した。

ミシシッピ渓谷では、北軍がほぼ連戦連勝していた。まずテネシー州で、南軍の長い戦列を分断することによって、同州西部をほぼすべて占拠した。ミシシッピ川の重要な港であるメンフィスを攻略した北軍は、南部連合の中心部へ約320キロメートル前進した。粘り強いユリシーズ・S・グラント将軍の率いる北軍は、シャイロのテネシー川を見下ろす断崖の上で、南軍の突然の反撃にあったが、持ちこたえた。シャイロの戦いでは、北軍と南軍の死傷者がそれぞれ1万人を超え、それまでの米国史上最大の死傷率となった。しかし、大量の殺りくは始まったばかりだった。

これに対してバージニア州では、北軍は南部連合の首都リッチモンドの攻略を何度も試みたが、激しい戦闘で敗北を続けた。南軍は、ワシントンとリッチモンドの間の道路を分断する多くの川によって、強力な防衛陣地を築くことができた。南軍の最も優秀な2人の将軍、ロバート・E・リーとトーマス・J・(「ストーンウォール」)ジャクソンは、いずれも初期の北軍の将軍たちに比べ、はるかに優れていた。1862年に、北軍の司令官ジョージ・マクレランは、リッチモンドを占拠すべく、ゆっくりと慎重すぎるペースで攻撃を試みた。しかし、6月25日から7月1日までの7日間の戦闘で、北軍は徐々に後退を余儀なくされ、両軍とも多大な損失を被った。

第2次ブルラン(別名第2次マナサス)の戦いで再び南軍が勝利を収めた後、リーはポトマック川を渡ってメリーランド州に侵入した。マクレランは、リーの軍隊が分割され、人数で大きく劣っていることを知っていたにもかかわらず、再び消極的な対応しかしなかった。北軍と南軍は、1862年9月17日、メリーランド州シャープスバーグ市に近いアンティータム川で交戦した。この戦いは、南北戦争で1日に最も多くの死傷者を出した戦いとなり、双方で4000人以上が戦死し、負傷者は1万8000人にのぼった。マクレランは、人数で勝っていたにもかかわらず、リーの戦列を崩すことも、攻撃を強行することもできず、リーは損害を受けずに再びポトマック川を渡って後退することができた。この戦いの後で、リンカーンはマクレランを解任した。

アンティータムでは、軍事的な決着はつかなかったが、その戦いの影響は多大であった。南部連合を承認しようとしていた英国とフランスが、その決断を先延ばしにし、南部連合は、切実に求めていたヨーロッパによる外交的承認と経済援助を得ることができなかった。

またアンティータムは、リンカーンに、予備的な奴隷解放宣言を発表する機会を与えた。これは、1863年1月1日をもって、連邦に反乱するすべての州の奴隷は自由であると宣言するものであった。実際的には、この宣言はほとんど直接的な影響を及ぼさなかった。これは南部連合諸州のみの奴隷を解放するもので、境界州の奴隷はそのままであった。しかしながら政治的には、北軍の戦争の目的として、連邦の維持に加えて奴隷制廃止を掲げる、という意味を持つものであった。

1863年1月1日に発表された最終的な奴隷解放宣言は、北軍がアフリカ系米国人を募集することをも承認していた。これは、フレデリック・ダグラスをはじめとする奴隷解放運動の指導者たちが、武力紛争の当初から要求していたことであった。北軍はすでに脱走奴隷を「戦時禁制品」としてかくまっていたが、奴隷解放宣言後、北軍はアフリカ系米国人兵士を募集・訓練し、こうしたアフリカ系米国人の連隊は、バージニア州からミシシッピ川まで各地の戦闘で手柄を立てた。約17万8000人のアフリカ系米国人が合衆国有色人種部隊に入り、また2万9500人が北軍の海軍に入隊した。

しかしながら、奴隷解放宣言による政治的な前進にもかかわらず、東部における北軍の軍事的な展望は引き続き思わしくなく、リー将軍の北バージニア軍は、まず1862年12月にバージニア州フレデリックスバーグで、続いて1863年5月にはチャンセラーズビルで、ポトマック川沿いの戦いにおいて北軍を打破し続けた。しかし、チャンセラーズビルの戦いは、リーの最も華々しい勝利のひとつであると同時に、最も大きな犠牲を出した戦いのひとつでもあった。この戦いで、リーにとって最も貴重な副官であった「ストーンウォール」ジャクソン将軍が、味方の銃弾によって戦死したのである。

しかし、南軍の勝利はいずれも決定的なものではなかった。北軍は毎回軍勢を立て直し、再度挑戦した。リーは、チャンセラーズビルで北軍に大勝したことで機会をとらえたと考え、1863年7月初めに北へ進軍してペンシルバニア州に入り、州都ハリスバーグ市に迫った。しかし、強力な北軍の部隊がゲティスバーグ市でリーの軍勢を迎え撃ち、南北戦争で最大の戦闘となる3日間に及ぶ大激戦が展開された。南軍は北軍の戦列を打ち破るべく勇敢に戦ったが敗れ、壊滅的な打撃を受けたリーの軍隊は、7月4日ポトマック川を渡って後退した。

ゲティスバーグの戦いでは、北軍の戦死者は3000人以上、南軍の戦死者は4000人近く、また負傷者・行方不明者の合計は南北でそれぞれ2万人を超えた。1863年11月19日、ゲティスバーグの新しい国立墓地の献納式でリンカーン大統領が行った演説は、おそらく米国史上最も有名な演説である。その短い演説の最後に、リンカーンはこう述べている。

「・・・これらの戦死者たちの死を無駄にしないと高らかに決意すること–この国が、神の導きの下で、自由の新たなる誕生をもたらすこと–そして、人民の、人民による、人民のための政府をこの地上から絶やさないこと・・・。」

ミシシッピ川沿いでは、ビックスバーグ市で、南軍が、海からの攻撃の届かない高い崖の上で防備を固め、北軍を阻止した。1863年初頭、グラント将軍はビックスバーグの南に回り、6週間に及ぶ包囲攻撃を続けた。7月4日、グラントはビックスバーグを攻略するとともに、西部における最強の南軍部隊を捕らえた。こうしてミシシッピ川はすべて北軍の支配下に置かれた。南軍は2つに分断され、テキサス州からアーカンソー州へ物資を運ぶことがほとんど不可能となった。

ビックスバーグ、そして1863年7月のゲティスバーグにおける北軍の勝利は、南北戦争の転換点となったが、その後も1年半以上にわたって激しい流血の戦いが全面的に継続した。

リンカーンは、グラントを東部に移し、北軍全体の司令官とした。1864年5月、グラントはバージニア州内に深く前進し、リー将軍の率いる南軍との間で、3日間にわたるウィルダネスの戦いが展開された。双方共に多大な損害を被ったが、他の北軍の司令官らと異なり、グラントは撤退を拒否した。彼は、砲撃と歩兵攻撃を続けることによって、南軍の戦列を分散させようとした。ほぼ1年間に及ぶ東部戦線での戦いを象徴するような5日間の激しい塹壕戦が行われたスポットシルバニアで、グラントは、「私は、ひと夏かかったとしても、この戦線で戦い続ける」と宣言した。

西では、1863年秋、北軍がチャタヌガおよびその近くのルックアウト・マウンテンにおける戦闘で勝利を収めてテネシー州を支配下に置き、ウィリアム・T・シャーマン将軍によるジョージア州侵攻への道を切り開いた。シャーマンは、いくつかの小規模な南軍部隊を打破し、ジョージア州の州都アトランタを占領した後、大西洋岸へ向かって進軍し、その途上で組織的に鉄道、工場、倉庫、その他の施設を破壊していった。シャーマンの部隊では通常の物資の補給が途絶えていたため、兵士たちは進軍途上の各地で食料をあさった。大西洋岸に到達すると、シャーマンはそこから北へ向かい、1865年2月までにはサウスカロライナ州チャールストン市を占領した。チャールストンは、南北戦争開戦のきっかけとなった砲撃の行われたところであった。シャーマンは、南軍に勝つためには、南軍の意欲と士気をくじくことが、戦闘に勝つことと同様に重要であることを、北軍の他のどの将軍よりも良く理解していた。

一方、グラント将軍は、バージニア州ピーターズバーグ市を9カ月間にわたって包囲した。1865年3月には、リー将軍が、ピーターズバーグと南部連合の首都リッチモンドの両市を放棄して南へ後退しなければならないと判断した。しかし時すでに遅く、1865年4月9日、大勢の北軍に包囲されたリーは、アポマトックス・コートハウスでグラント将軍に降伏した。その後も数カ月間にわたって各地で戦闘が散発したが、南北戦争はこれをもって終結した。

アポマトックスでの降伏の条件は寛大なものであり、リーとの会見から戻ったグラントは、声高に抗議する兵士たちに対して、「反乱軍は再び同胞となったのだ」と説いた。南部の独立のための戦争は「失われた大義」となり、その戦いの英雄ロバート・E・リーは、優れたリーダーシップと、敗者としての潔さによって、広く尊敬を集めた。

北部では、この戦争はさらに偉大な英雄を生んだ。力と抑圧によってではなく温情と寛容によって連邦を再び統一することを何よりも優先させたエイブラハム・リンカーンである。1864 年に、彼は対立候補のジョージ・マクレランを破って大統領に再選されていた。マクレランは、アンティータムの戦いの後にリンカーンが解雇した将軍であった。リンカーンは、第2期目の就任演説を次のように結んだ。

「何人にも悪意を抱かず、すべての人に対して愛を持ち、神が私たちに示したその正義の確信によって、私たちが今取り組んでいる課題を成し遂げるため努力しようではないか。国の傷をいやし、戦争に従軍した人とその未亡人や子どもを助け、私たちの間とそしてすべての国の間に正しくそして永続する平和を達成し育むためにあらゆる努力を尽くそうではないか。」

その3週間後、そしてリー将軍の降伏から2日後、リンカーンは国民に向けた、最後となる演説をし、寛大な再建政策を発表した。そして1865年4月14日、彼にとって最後の閣僚会議を開いた。その晩リンカーン夫妻は、若いカップルを招いて、観劇のためフォード劇場へ出かけた。そこで大統領用の観劇席に座ろうとしたリンカーンは、南軍の敗北を恨んだバージニア州出身の俳優ジョン・ウィルクス・ブースに撃たれた。ブースは、その数日後バージニア州の田舎の納屋で撃ち合いの末射殺され、ブースの共謀者らも逮捕されて、後に処刑された。

リンカーンは、フォード劇場の向かいの家に運ばれ、その1階の寝室で、4月15日朝死去した。詩人のジェームズ・ラッセル・ローウェルは、次のように書いた。

「あの驚愕に満ちた4月の朝までは、あれほど多くの人々が、一度も会ったことのない者の死に対して、自分の人生から親しい存在が奪われた後に冷ややかな暗黒が残されたかのように、涙を流すことはなかった。また、いかなる葬儀における弔辞も、あの日、見知らぬ者同士が黙って取り交わした悲しみの表情ほど雄弁ではなかった。彼らは人間として共通の同胞を失ったのである。」

勝利を収めた北部が直面した最初の大事業は、脱退した南部諸州の立場を決定することであり、それを主導したのは、リンカーンの後を継いだアンドリュー・ジョンソン副大統領であった。ジョンソンは南部人であったが、終始連邦側に立っていた。南部諸州の扱いについては、リンカーンがすでに準備を進めていた。リンカーンは、南部諸州の人々は法的に脱退したのではなく、一部の不実な国民に惑わされて連邦政府の権威に反抗していたのだと考えた。そして、この戦争は個々の人々による行為であったため、連邦政府は各州ではなくこうした個人に対処しなければならない、と考えた。従って、1863年にリンカーンは、1860年の時点で州の有権者の10%以上が、合衆国憲法に忠実な政府を設立し連邦議会の法律および大統領の宣言に従うことを承認したならば、そのように設立された政府をその州の法的な政府として承認する、と宣言した。

しかし連邦議会はこの計画を拒否した。多くの共和党議員は、これが南部連合の反乱者たちに足場を固めさせる結果となることを恐れ、リンカーンが協議なしで脱退州に対応する権利に異議を唱えた。一部の議員は、脱退したすべての州を厳しく処罰することを支持した。また、旧南部の支配層が再び権力を得たならば、この戦争は無駄であったことになると考える議員らもいた。しかし、南北戦争が完全に終結する前に、すでにバージニア、テネシー、アーカンソー、およびルイジアナの各州に新しい政府が確立されていた。

連邦議会は、主要な関心事のひとつであった元奴隷の扱いに関して、1865年3月、解放民局を設置した。同局は、アフリカ系米国人の保護者の役割を果たし、彼らを自立へ導くことを目的としていた。そして同年12月、議会は、奴隷制を廃止する合衆国憲法修正第13条を批准した。

1865年の夏を通じて、ジョンソン大統領は、リンカーンの再建計画を、多少の修正を加えて実行しようとした。彼は、大統領声明によって、旧南部連合の各州の知事を任命し、また大統領恩赦を利用して多くの南部人の政治的権利を広く復活させた。

その後、旧南部連合の各州で、連邦脱退の布告を撤回し、戦債の返済を拒否し、新たな州憲法の草案を作成するために、会議が開かれた。最終的には各州で北部生まれの連邦主義者が知事となり、忠実な有権者たちの会議を招集する権限を与えられた。ジョンソンは各州の会議に対して、連邦脱退を無効とし、奴隷制を廃止し、南部連合の支援を目的とするすべての戦債の返済を拒否し、合衆国憲法修正第13条を批准することを求めた。1865年末までには、多少の例外を除いて、この過程は完了した。

合衆国憲法の「各議院は、その議員の・・・資格について判定を行う」という一節の下で、連邦議会が、上院または下院の議席を南部出身者に与えることを拒否する権利を有することを、リンカーンもジョンソンも予見していなかった。こうした事態が発生したのは、サディアス・スティーブンズの率いる「急進的共和党員」と呼ばれる議員の一団が、迅速かつ安易な「再建」を憂慮し、新たに選出された南部出身の上院および下院議員を着任させることを拒否したためである。その後数カ月間にわたって、議会は、リンカーンが着手しジョンソンが引き継いだ再建計画とはかなり異なる計画を進めることになった。

アフリカ系米国人にも全面的な市民権が与えられるべきであるとする議員を支持する世論が徐々に広がっていった。1866年7月までには、議会は公民権法案を通過させ、解放民局を新設していた。これはいずれも、南部出身の議員らによる人種的差別を防止することを目的としていた。続いて議会は、「合衆国において出生し、またはこれに帰化し、その管轄権に服するすべての者は、合衆国およびその居住する州の市民である」とする合衆国憲法修正第14条を可決した。 これは、奴隷の市民権を拒否したドレッド・スコット事件の判決を否定するものであった。

テネシー州を除くすべての南部諸州の議会は、この修正条項の批准を拒否し、全員一致で否決した州もいくつかあった。さらに、南部諸州の議会は、アフリカ系米国人の解放民を規制する「規約」を可決した。こうした規約の内容は州によって異なったが、共通する条項がいくつかあった。アフリカ系米国人は、年次の労働契約を結ぶことを義務付けられ、違反すれば懲罰を課された。また、扶養家族である子どもは、年季奉公の義務および主人による体罰の対象となった。放浪者は、多額の罰金を課され、それを支払うことができなければ私有の奉公人として売ることができた。

多くの北部人は、こうした南部の対応を、奴隷制を再び確立し、北部が苦労して得た南北戦争の勝利を拒否するもの、と解釈した。ジョンソン大統領自身が、連邦主義者ではあったが、南部出身の民主党員であり、抑制の効かない弁舌を振るい、政治的妥協を拒否する傾向があったことも、マイナス要因となった。1866年の連邦議会選挙では、共和党が圧勝した。権力を固めた急進派は、独自の再建のビジョンを強硬に押し出した。

1867年3月の再建法では、連邦議会は、南部諸州で設立されていた州政府を無視し、南部を5つの軍管区に分割し、その各区を北部の将軍に管理させた。民間政府を設立し、修正第14条を批准し、アフリカ系米国人の参政権を認めた州は、永久的な軍政から逃れることができた。南部連合の支持者で、合衆国への忠誠を誓わなかった者は、概して投票権を与えられなかった。修正第14条は、1868年に批准された。翌年には、「合衆国市民の投票権は、人種、体色または過去における労役の状態を理由として、合衆国または州によって拒否または制限されることはない」とする修正第15条が連邦議会で可決され、1870年には各州議会で批准された。

ジョンソン大統領が、新たに解放されたアフリカ系米国人を保護し、旧南部連合の指導者たちを罰するために被選挙権を剥奪する法案に対して拒否権を発動したことは(これは最終的には覆されたが)、連邦議会の急進派共和党員を激怒させた。ジョンソンに対する議会の反感は最高潮に達し、米国史上初めて、大統領を罷免するための弾劾手続きが開始された。

ジョンソンの主な罪は、連邦議会の懲罰的な政策に反対したことと、その批判に際して乱暴な発言をしたことであった。ジョンソンの最も重大な法的な罪として、彼の敵が告発することができたのは、ジョンソンが在職期限法に反して、連邦議会の強力な支持者であった陸軍長官を解雇したことであった(在職期限法では、上院によって承認された公職者を解雇するには、上院の承認が必要であることが定められていた)。上院で弾劾裁判が行われ、厳密に言えばジョンソンにはその閣僚を解雇する権限があったことが証明された。さらに重要なこととして、大統領が連邦議会議員の過半数と意見が合わないからといって議会が大統領を解雇したならば、危険な前例を作ることになるという点が指摘された。最終的な投票では、有罪判決に必要な3分の2の得票に1票足りなかった。

ジョンソン大統領は、1869年の任期終了まで在職したが、連邦議会は支配的勢力を確立し、それは19世紀を通じて続いた。1868年の大統領選挙で勝利を収めた共和党のユリシーズ・S・グラント元北軍将軍は、急進派が着手していた再建政策を実行した。

1868年6月までには、連邦議会は旧南部連合諸州の大半を連邦に復活させた。これらの再建された州の多くでは、州知事や下院および上院議員の大半は北部人の男性であり、南北戦争後、政治の世界での成功を求めて南部へ移住した人々であった(こうした北部人は「カーペットバッガー」と呼ばれた)。その中には、新たに解放されたアフリカ系米国人と提携する人々も多かった。事実、ルイジアナ州とサウスカロライナ州の議会では、アフリカ系米国人が議席の過半数を占めた。

政治的・社会的優勢を脅かされた多くの南部の白人は、違法な手段でアフリカ系米国人の平等獲得を妨げようとした。クー・クラックス・クラン(KKK)のような超法規的組織による、アフリカ系米国人に対する暴力が、より頻繁に発生するようになった。混乱の悪化に伴い、1870年および1871年には執行法が可決され、アフリカ系米国人の解放民の公民権を奪おうとする者は厳しく処罰されることになった。

時と共に、厳しい法律や、旧南部連合に対する憎悪は、南部の諸問題を解決することにはならないということが、ますます明らかになってきた。また、著名なアフリカ系米国人を指導層に持つ、南部の一部の急進派州政府に、腐敗と非効率が見られるようになった。 米国は、北部が南部に銃剣を突き付けて急進的民主主義と自由主義的価値観を強要しようとすることに疑問を持ち始めていた。1872年5月、連邦議会は総合的な恩赦法を可決し、旧反乱軍のおよそ500人を除く全員に、政治権を全面的に復活させた。

南部諸州は徐々に民主党員を公職に選出し始め、カーペットバッガーから成る政府を排除し、またアフリカ系米国人を脅かして、彼らが投票をしたり公職に就いたりすることを妨げた。1876年までには、南部で共和党が権力を維持した州はわずか3州となっていた。 同年の大統領選挙をめぐる紛争で、共和党は、ラザフォード・B・ヘイズを勝者とすることと交換に、残る共和党州政府を支援していた連邦軍兵士を撤退させることを約束した。1877年、へイズはこの約束を守り、黒人の公民権を執行するという連邦政府の責任を放棄することを黙認した。

南部は、依然として戦争による荒廃が残り、失政による債務を負担し、10年間に及ぶ人種紛争によって士気を喪失していた。残念なことに、米国の人種政策は極端に変質していた。南部の白人指導者らに対する厳しい懲罰を支持していた連邦政府が、アフリカ系米国人に対する新たな侮辱的な差別を容認するようになっていた。19世紀の最後の四半世紀には、南部諸州で、公立学校を人種によって分離し、アフリカ系米国人による公園、レストラン、ホテルなどの公共施設の利用を禁止または制限し、人頭税や恣意的な識字能力試験を課すことによって黒人の大半に投票権を与えないようにする「ジム・クロー」法(黒人差別法)が多数制定された。「ジム・クロー」とは、1828年に初めて白人が黒人に扮して「ブラックフェース」を演じたミンストレル・ショーの歌にちなんで付けられた名称である。

歴史家たちは、概して再建時代を、政治闘争と腐敗と退化の不透明な時代として、また当初の高邁な目標を達成することができず、悪意に満ちた人種主義の深みに落ち込んだ時代として、厳しく評価してきた。奴隷は自由を与えられたが、北部の人々は奴隷たちの経済的ニーズに全く対応することができなかった。解放民局は、解放された奴隷たちに政治的・経済的な機会を与えることができなかった。北軍の占領軍は、元奴隷たちを暴力や脅迫から守ることすらできないことが多く、事実、連邦軍の将校や解放民局の職員にも人種差別主義者が多かった。独自の経済力を持たなかった南部の多くのアフリカ系米国人は、元の主人の所有する土地で小作人となるしか道がなく、20世紀に入ってからも長い間こうした貧困の悪循環にとらわれていた。

再建時代の各州政府は、南北戦争で荒廃した南部諸州の再建を大きく前進させ、公共サービスを拡大させた。特に注目すべき点として、アフリカ系米国人と白人のための、税金による無料の公立学校を設立した。しかしながら、反抗的な南部人は、腐敗が発生するとその機会をとらえて(腐敗はこの時代の南部だけに限られることではなかったが)、急進派政権を打倒するためにこれを利用した。再建の失敗は、アフリカ系米国人の平等と自由を求める闘争が20世紀まで持ち越されることを意味した。20世紀には、この闘争が南部のみにとどまらず全国的な問題となっていくのである。

|

The Civil War and Reconstruction

“That this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom.”

-- President Abraham Lincoln, November 19, 1863

SECESSION AND CIVIL WAR

Lincoln’s victory in the presidential election of November 1860 made South Carolina’s secession from the Union December 20 a foregone conclusion. The state had long been waiting for an event that would unite the South against the antislavery forces. By February 1, 1861, five more Southern states had seceded. On February 8, the six states signed a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America. The remaining Southern states as yet remained in the Union, although Texas had begun to move on its secession.

Less than a month later, March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as president of the United States. In his inaugural address, he declared the Confederacy “legally void.” His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union, but the South turned a deaf ear. On April 12, Confederate guns opened fire on the federal garrison at Fort Sumter in the Charleston, South Carolina, harbor. A war had begun in which more Americans would die than in any other conflict before or since.

In the seven states that had seceded, the people responded positively to the Confederate action and the leadership of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Both sides now tensely awaited the action of the slave states that thus far had remained loyal. Virginia seceded on April 17; Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina followed quickly.

No state left the Union with greater reluctance than Virginia. Her statesmen had a leading part in the winning of the Revolution and the framing of the Constitution, and she had provided the nation with five presidents. With Virginia went Colonel Robert E. Lee, who declined the command of the Union Army out of loyalty to his native state.

Between the enlarged Confederacy and the free‑soil North lay the border slave states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, which, despite some sympathy with the South, would remain loyal to the Union.

Each side entered the war with high hopes for an early victory. In material resources the North enjoyed a decided advantage. Twenty‑three states with a population of 22 million were arrayed against 11 states inhabited by nine million, including slaves. The industrial superiority of the North exceeded even its preponderance in population, providing it with abundant facilities for manufacturing arms and ammunition, clothing, and other supplies. It had a greatly superior railway network.

The South nonetheless had certain advantages. The most important was geography; the South was fighting a defensive war on its own territory. It could establish its independence simply by beating off the Northern armies. The South also had a stronger military tradition, and possessed the more experienced military leaders.

WESTERN ADVANCE, EASTERN STALEMATE

The first large battle of the war, at Bull Run, Virginia (also known as First Manassas) near Washington, stripped away any illusions that victory would be quick or easy. It also established a pattern, at least in the Eastern United States, of bloody Southern victories that never translated into a decisive military advantage for the Confederacy.

In contrast to its military failures in the East, the Union was able to secure battlefield victories in the West and slow strategic success at sea. Most of the Navy, at the war’s beginning, was in Union hands, but it was scattered and weak. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles took prompt measures to strengthen it. Lincoln then proclaimed a blockade of the Southern coasts. Although the effect of the blockade was negligible at first, by 1863 it almost completely prevented shipments of cotton to Europe and blocked the importation of sorely needed munitions, clothing, and medical supplies to the South.

A brilliant Union naval commander, David Farragut, conducted two remarkable operations. In April 1862, he took a fleet into the mouth of the Mississippi River and forced the surrender of the largest city in the South, New Orleans, Louisiana. In August 1864, with the cry, “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead,” he led a force past the fortified entrance of Mobile Bay, Alabama, captured a Confederate ironclad vessel, and sealed off the port.

In the Mississippi Valley, the Union forces won an almost uninterrupted series of victories. They began by breaking a long Confederate line in Tennessee, thus making it possible to occupy almost all the western part of the state. When the important Mississippi River port of Memphis was taken, Union troops advanced some 320 kilometers into the heart of the Confederacy. With the tenacious General Ulysses S. Grant in command, they withstood a sudden Confederate counterattack at Shiloh, on the bluffs overlooking the Tennessee River. Those killed and wounded at Shiloh numbered more than 10,000 on each side, a casualty rate that Americans had never before experienced. But it was only the beginning of the carnage.

In Virginia, by contrast, Union troops continued to meet one defeat after another in a succession of bloody attempts to capture Richmond, the Confederate capital. The Confederates enjoyed strong defense positions afforded by numerous streams cutting the road between Washington and Richmond. Their two best generals, Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. (“Stonewall”) Jackson, both far surpassed in ability their early Union counterparts. In 1862 Union commander George McClellan made a slow, excessively cautious attempt to seize Richmond. But in the Seven Days’ Battles between June 25 and July 1, the Union troops were driven steadily backward, both sides suffering terrible losses.

After another Confederate victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run (or Second Manassas), Lee crossed the Potomac River and invaded Maryland. McClellan again responded tentatively, despite learning that Lee had split his army and was heavily outnumbered. The Union and Confederate Armies met at Antietam Creek, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, in the bloodiest single day of the war: More than 4,000 died on both sides and 18,000 were wounded. Despite his numerical advantage, however, McClellan failed to break Lee’s lines or press the attack, and Lee was able to retreat across the Potomac with his army intact. As a result, Lincoln fired McClellan.

Although Antietam was inconclusive in military terms, its consequences were nonetheless momentous. Great Britain and France, both on the verge of recognizing the Confederacy, delayed their decision, and the South never received the diplomatic recognition and the economic aid from Europe that it desperately sought.

Antietam also gave Lincoln the opening he needed to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all slaves in states rebelling against the Union were free. In practical terms, the proclamation had little immediate impact; it freed slaves only in the Confederate states, while leaving slavery intact in the border states. Politically, however, it meant that in addition to preserving the Union, the abolition of slavery was now a declared objective of the Union war effort.

The final Emancipation Proclamation, issued January 1, 1863, also authorized the recruitment of African Americans into the Union Army, a move abolitionist leaders such as Frederick Douglass had been urging since the beginning of armed conflict. Union forces already had been sheltering escaped slaves as “contraband of war,” but following the Emancipation Proclamation, the Union Army recruited and trained regiments of African-American soldiers that fought with distinction in battles from Virginia to the Mississippi. About 178,000 African Americans served in the U.S. Colored Troops, and 29,500 served in the Union Navy.

Despite the political gains represented by the Emancipation Proclamation, however, the North’s military prospects in the East remained bleak as Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia continued to maul the Union Army of the Potomac, first at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862 and then at Chancellorsville in May 1863. But Chancellorsville, although one of Lee’s most brilliant military victories, was also one of his most costly. His most valued lieutenant, General “Stonewall” Jackson, was mistakenly shot and killed by his own men.

GETTYSBURG TO APPOMATTOX

Yet none of the Confederate victories was decisive. The Union simply mustered new armies and tried again. Believing that the North’s crushing defeat at Chancellorsville gave him his chance, Lee struck northward into Pennsylvania at the beginning of July 1863, almost reaching the state capital at Harrisburg. A strong Union force intercepted him at Gettysburg, where, in a titanic three‑day battle – the largest of the Civil War – the Confederates made a valiant effort to break the Union lines. They failed, and on July 4 Lee’s army, after crippling losses, retreated behind the Potomac.

More than 3,000 Union soldiers and almost 4,000 Confederates died at Gettysburg; wounded and missing totaled more than 20,000 on each side. On November 19, 1863, Lincoln dedicated a new national cemetery there with perhaps the most famous address in U.S. history. He concluded his brief remarks with these words:

... we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain –

that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that

government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish

from the earth.

On the Mississippi, Union control had been blocked at Vicksburg, where the Confederates had strongly fortified themselves on bluffs too high for naval attack. In early 1863 Grant began to move below and around Vicksburg, subjecting it to a six‑week siege. On July 4, he captured the town, together with the strongest Confederate Army in the West. The river was now entirely in Union hands. The Confederacy was broken in two, and it became almost impossible to bring supplies from Texas and Arkansas.

The Northern victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in July 1863 marked the turning point of the war, although the bloodshed continued unabated for more than a year‑and‑a‑half.

Lincoln brought Grant east and made him commander‑in‑chief of all Union forces. In May 1864 Grant advanced deep into Virginia and met Lee’s Confederate Army in the three‑day Battle of the Wilderness. Losses on both sides were heavy, but unlike other Union commanders, Grant refused to retreat. Instead, he attempted to outflank Lee, stretching the Confederate lines and pounding away with artillery and infantry attacks. “I propose to fight it out along this line if it takes all summer,” the Union commander said at Spotsylvania, during five days of bloody trench warfare that characterized fighting on the eastern front for almost a year.

In the West, Union forces gained control of Tennessee in the fall of 1863 with victories at Chattanooga and nearby Lookout Mountain, opening the way for General William T. Sherman to invade Georgia. Sherman outmaneuvered several smaller Confederate armies, occupied the state capital of Atlanta, then marched to the Atlantic coast, systematically destroying railroads, factories, warehouses, and other facilities in his path. His men, cut off from their normal supply lines, ravaged the countryside for food. From the coast, Sherman marched northward; by February 1865, he had taken Charleston, South Carolina, where the first shots of the Civil War had been fired. Sherman, more than any other Union general, understood that destroying the will and morale of the South was as important as defeating its armies.

Grant, meanwhile, lay siege to Petersburg, Virginia, for nine months, before Lee, in March 1865, knew that he had to abandon both Petersburg and the Confederate capital of Richmond in an attempt to retreat south. But it was too late. On April 9, 1865, surrounded by huge Union armies, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse. Although scattered fighting continued elsewhere for several months, the Civil War was over.

The terms of surrender at Appomattox were magnanimous, and on his return from his meeting with Lee, Grant quieted the noisy demonstrations of his soldiers by reminding them: “The rebels are our countrymen again.” The war for Southern independence had become the “lost cause,” whose hero, Robert E. Lee, had won wide admiration through the brilliance of his leadership and his greatness in defeat.

WITH MALICE TOWARD NONE

For the North, the war produced a still greater hero in Abraham Lincoln – a man eager, above all else, to weld the Union together again, not by force and repression but by warmth and generosity. In 1864 he had been elected for a second term as president, defeating his Democratic opponent, George McClellan, the general he had dismissed after Antietam. Lincoln’s second inaugural address closed with these words:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right,

as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are

in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the

battle, and for his widow, and his orphan – to do all which may achieve and

cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Three weeks later, two days after Lee’s surrender, Lincoln delivered his last public address, in which he unfolded a generous reconstruction policy. On April 14, 1865, the president held what was to be his last Cabinet meeting. That evening – with his wife and a young couple who were his guests – he attended a performance at Ford’s Theater. There, as he sat in the presidential box, he was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, a Virginia actor embittered by the South’s defeat. Booth was killed in a shootout some days later in a barn in the Virginia countryside. His accomplices were captured and later executed.

Lincoln died in a downstairs bedroom of a house across the street from Ford’s Theater on the morning of April 15. Poet James Russell Lowell wrote:

Never before that startled April morning did such multitudes of men shed

tears for the death of one they had never seen, as if with him a friendly

presence had been taken from their lives, leaving them colder and darker.

Never was funeral panegyric so eloquent as the silent look of sympathy which

strangers exchanged when they met that day. Their common manhood had

lost a kinsman.

The first great task confronting the victorious North – now under the leadership of Lincoln’s vice president, Andrew Johnson, a Southerner who remained loyal to the Union – was to determine the status of the states that had seceded. Lincoln had already set the stage. In his view, the people of the Southern states had never legally seceded; they had been misled by some disloyal citizens into a defiance of federal authority. And since the war was the act of individuals, the federal government would have to deal with these individuals and not with the states. Thus, in 1863 Lincoln proclaimed that if in any state 10 percent of the voters of record in 1860 would form a government loyal to the U.S. Constitution and would acknowledge obedience to the laws of the Congress and the proclamations of the president, he would recognize the government so created as the state’s legal government.

Congress rejected this plan. Many Republicans feared it would simply entrench former rebels in power; they challenged Lincoln’s right to deal with the rebel states without consultation. Some members of Congress advocated severe punishment for all the seceded states; others simply felt the war would have been in vain if the old Southern establishment was restored to power. Yet even before the war was wholly over, new governments had been set up in Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

To deal with one of its major concerns – the condition of former slaves – Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau in March 1865 to act as guardian over African Americans and guide them toward self‑support. And in December of that year, Congress ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery.

Throughout the summer of 1865 Johnson proceeded to carry out Lincoln’s reconstruction program, with minor modifications. By presidential proclamation he appointed a governor for each of the former Confederate states and freely restored political rights to many Southerners through use of presidential pardons.

In due time conventions were held in each of the former Confederate states to repeal the ordinances of secession, repudiate the war debt, and draft new state constitutions. Eventually a native Unionist became governor in each state with authority to convoke a convention of loyal voters. Johnson called upon each convention to invalidate the secession, abolish slavery, repudiate all debts that went to aid the Confederacy, and ratify the 13th Amendment. By the end of 1865, this process was completed, with a few exceptions.

RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION

Both Lincoln and Johnson had foreseen that the Congress would have the right to deny Southern legislators seats in the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives, under the clause of the Constitution that says, “Each house shall be the judge of the ... qualifications of its own members.” This came to pass when, under the leadership of Thaddeus Stevens, those congressmen called “Radical Republicans,” who were wary of a quick and easy “reconstruction,” refused to seat newly elected Southern senators and representatives. Within the next few months, Congress proceeded to work out a plan for the reconstruction of the South quite different from the one Lincoln had started and Johnson had continued.

Wide public support gradually developed for those members of Congress who believed that African Americans should be given full citizenship. By July 1866, Congress had passed a civil rights bill and set up a new Freedmen’s Bureau – both designed to prevent racial discrimination by Southern legislatures. Following this, the Congress passed a 14th Amendment to the Constitution, stating that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” This repudiated the Dred Scott ruling, which had denied slaves their right of citizenship.

All the Southern state legislatures, with the exception of Tennessee, refused to ratify the amendment, some voting against it unanimously. In addition, Southern state legislatures passed “codes” to regulate the African-American freedmen. The codes differed from state to state, but some provisions were common. African Americans were required to enter into annual labor contracts, with penalties imposed in case of violation; dependent children were subject to compulsory apprenticeship and corporal punishments by masters; vagrants could be sold into private service if they could not pay severe fines.

Many Northerners interpreted the Southern response as an attempt to reestablish slavery and repudiate the hard-won Union victory in the Civil War. It did not help that Johnson, although a Unionist, was a Southern Democrat with an addiction to intemperate rhetoric and an aversion to political compromise. Republicans swept the congressional elections of 1866. Firmly in power, the Radicals imposed their own vision of Reconstruction.

In the Reconstruction Act of March 1867, Congress, ignoring the governments that had been established in the Southern states, divided the South into five military districts, each administered by a Union general. Escape from permanent military government was open to those states that established civil governments, ratified the 14th Amendment, and adopted African-American suffrage. Supporters of the Confederacy who had not taken oaths of loyalty to the United States generally could not vote. The 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868. The 15th Amendment, passed by Congress the following year and ratified in 1870 by state legislatures, provided that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The Radical Republicans in Congress were infuriated by President Johnson’s vetoes (even though they were overridden) of legislation protecting newly freed African Americans and punishing former Confederate leaders by depriving them of the right to hold office. Congressional antipathy to Johnson was so great that, for the first time in American history, impeachment proceedings were instituted to remove the president from office.

Johnson’s main offense was his opposition to punitive congressional policies and the violent language he used in criticizing them. The most serious legal charge his enemies could level against him was that, despite the Tenure of Office Act (which required Senate approval for the removal of any officeholder the Senate had previously confirmed), he had removed from his Cabinet the secretary of war, a staunch supporter of the Congress. When the impeachment trial was held in the Senate, it was proved that Johnson was technically within his rights in removing the Cabinet member. Even more important, it was pointed out that a dangerous precedent would be set if the Congress were to remove a president because he disagreed with the majority of its members. The

final vote was one short of the two-thirds required for conviction.

Johnson continued in office until his term expired in 1869, but Congress had established an ascendancy that would endure for the rest of the century. The Republican victor in the presidential election of 1868, former Union general Ulysses S. Grant, would enforce the reconstruction policies the Radicals had initiated.

By June 1868, Congress had readmitted the majority of the former Confederate states back into the Union. In many of these reconstructed states, the majority of the governors, representatives, and senators were Northern men – so‑called carpetbaggers – who had gone South after the war to make their political fortunes, often in alliance with newly freed African Americans. In the legislatures of Louisiana and South Carolina, African Americans actually gained a majority of the seats.

Many Southern whites, their political and social dominance threatened, turned to illegal means to prevent African Americans from gaining equality. Violence against African Americans by such extra-legal organizations as the Ku Klux Klan became more and more frequent. Increasing disorder led to the passage of Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871, severely punishing those who attempted to deprive the African-American freedmen of their civil rights.

THE END OF RECONSTRUCTION

As time passed, it became more and more obvious that the problems of the South were not being solved by harsh laws and continuing rancor against former Confederates. Moreover, some Southern Radical state governments with prominent African-American officials appeared corrupt and inefficient. The nation was quickly tiring of the attempt to impose racial democracy and liberal values on the South with Union bayonets. In May 1872, Congress passed a general Amnesty Act, restoring full political rights to all but about 500 former rebels.

Gradually Southern states began electing members of the Democratic Party into office, ousting carpetbagger governments and intimidating African Americans from voting or attempting to hold public office. By 1876 the Republicans remained in power in only three Southern states. As part of the bargaining that resolved the disputed presidential elections that year in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republicans promised to withdraw federal troops that had propped up the remaining Republican governments. In 1877 Hayes kept his promise, tacitly abandoning federal responsibility for enforcing blacks’ civil rights.

The South was still a region devastated by war, burdened by debt caused by misgovernment, and demoralized by a decade of racial warfare. Unfortunately, the pendulum of national racial policy swung from one extreme to the other. A federal government that had supported harsh penalties against Southern white leaders now tolerated new and humiliating kinds of discrimination against African Americans. The last quarter of the 19th century saw a profusion of “Jim Crow” laws in Southern states that segregated public schools, forbade or limited African-American access to many public facilities such as parks, restaurants, and hotels, and denied most blacks the right to vote by imposing poll taxes and arbitrary literacy tests. “Jim Crow” is a term derived from a song in an 1828 minstrel show where a white man first performed in “blackface.”

Historians have tended to judge Reconstruction harshly, as a murky period of political conflict, corruption, and regression that failed to achieve its original high-minded goals and collapsed into a sinkhole of virulent racism. Slaves were granted freedom, but the North completely failed to address their economic needs. The Freedmen’s Bureau was unable to provide former slaves with political and economic opportunity. Union military occupiers often could not even protect them from violence and intimidation. Indeed, federal army officers and agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau were often racists themselves. Without economic resources of their own, many Southern African Americans were forced to become tenant farmers on land owned by their former masters, caught in a cycle of poverty that would continue well into the 20th century.

Reconstruction‑era governments did make genuine gains in rebuilding Southern states devastated by the war, and in expanding public services, notably in establishing tax‑supported, free public schools for African Americans and whites. However, recalcitrant Southerners seized upon instances of corruption (hardly unique to the South in this era) and exploited them to bring down radical regimes. The failure of Reconstruction meant that the struggle of African Americans for equality and freedom was deferred until the 20th century – when it would become a national, not just a Southern issue.